Cutting Room Idol

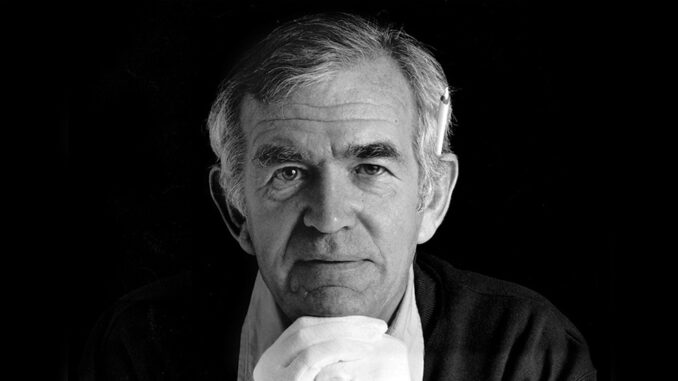

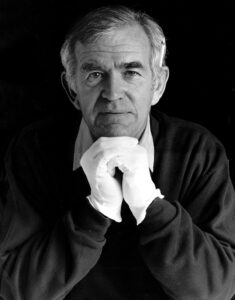

Jim Clark

Picture Editor

May 24, 1931 –

February 25, 2016

by Arthur Schmidt, ACE

I was working as an assistant editor on a film that was to be the sequel to 1977’s The Goodbye Girl, with Mike Nichols directing and Dede Allen, ACE, editing. I had worked with Mike as an assistant editor on The Fortune (1975) and with Dede as an assistant on Little Big Man (1970). I was thrilled to be working again with two of my heroes when, two weeks into shooting, the film was abruptly cancelled due to “creative differences” between Mike and the leading man. I was suddenly out of what I thought was my ideal job. Dede had even promised me a chance to edit.

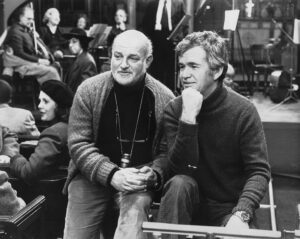

Desperate to find a new job, I bought the Daily Variety, went to the “Films in the Future” section, came to Marathon Man and started running down the credits: Dustin Hoffman and Laurence Olivier starring, John Schlesinger directing, William Goldman writing the screenplay, Conrad Hall, ASC, as DP and Jim Clark as editor. I had been a big fan of Jim’s since I had seen his inspired work on The Innocents (1961), The Pumpkin Eater (1964) and Darling (1965).

When I saw that he was going to edit Marathon Man (1976), I immediately called Paul Haggar, Paramount’s post-production supervisor, to see if an assistant had been hired yet, and he said, “Yes…well, sort of, but why don’t you come in and let’s talk.” It turned out that Paul had already assigned a female assistant to the job but Jim was not too crazy about having a female assistant because the last time he had one, he ended up marrying her! So Paul dialed Jim in London, Jim and I talked and, by the end of the conversation, I had the job. Great, now I would be working with another one of my idols.

I had been an assistant editor for almost nine years and was dying for the opportunity to cut. Jim was finishing editing The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter Brother, which overlapped with the beginning of Marathon Man. By the time Jim started on MM, he was about two months behind, and the film had piled up un-edited.

After about a week or two, he reluctantly started giving me scenes to cut, sometimes to re-cut scenes he had cut. “Just see if you can make it better,” he said — a rather daunting task to try and improve the master’s work. But he liked what I did and kept giving me more scenes.

Jim went back to London and I went to my father-in-law’s place in Italy for a little R&R after our rather intense post-production. I had been there a couple of weeks when Jim called and asked if I would come and help him out on Marty Feldman’s The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977). Marty had fired his first editor and hired Jim, with whom he had previously worked. I joined Jim at Twickenham Studios as an editor and he gave me the task of re-editing the previous editor’s work, as well as new scenes. At the end of shooting, we went to Universal Studios to finish editing with Marty and to show the film to executives at Universal — who were not at all happy with what they saw.

After the screening, Verna Fields, the post-production executive and former editor for Steven Spielberg, called us into her office and said, “Here’s what we are going to do. Jim and I will do the studio’s version and Artie will do Marty’s version.” And I replied to Verna that I did not want to do Marty’s version. And when she asked, “Why not?” I replied that my friendship with Jim was too important to me and I had seen what happens to friendships when editors are forced into doing dueling versions of a film. She paused and said, “OK, then you can work with Jim on the studio version and Jim’s assistant can help Marty with his version.” And that’s what we did. We took both versions to preview and they both tested the same, so we combined what we thought was the best of both versions. Jim returned to London but, Jim being Jim — and a great letter writer — he kept our friendship going with his (pre-e-mail) correspondence.

While working with director Michael Apted on Agatha (1979), Michael asked Jim to recommend an American editor for his next film, Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980). Jim recommended me and Michael hired me on the strength of his recommendation. It was my first solo feature and my first Oscar nomination. Before that, I was working on my first TV movie, The Jericho Mile (1979), a film that I took over from another editor with whom Michael Mann, the director, was not happy. It was full of difficult scenes that didn’t seem to want to go together in any conventional way. So I asked myself, “What would Jim do?” and I knew he’d throw caution to the wind and be bold. That’s all I needed. Jim was my inspiration, and I ended up winning an Emmy and an ACE Eddie Award for the Best Edited TV Movie.

Several years later, I was working again with Michael on Firstborn (1984). There were two teenage boys in the movie and Bob Zemeckis called Michael and asked if he could take a look at the boys. Bob was looking for somebody to play the Marty McFly character in his next movie, Back to the Future (1985). Michael was still shooting the film so he asked Bob and his two producers to come and run some scenes on the KEM with me in the cutting room. After running three or four scenes for Bob, we stopped and there was no comment from him or the producers, just a long silence! So I asked, “Well, what did you think of the boys?”

Several years later, I was working again with Michael on Firstborn (1984). There were two teenage boys in the movie and Bob Zemeckis called Michael and asked if he could take a look at the boys. Bob was looking for somebody to play the Marty McFly character in his next movie, Back to the Future (1985). Michael was still shooting the film so he asked Bob and his two producers to come and run some scenes on the KEM with me in the cutting room. After running three or four scenes for Bob, we stopped and there was no comment from him or the producers, just a long silence! So I asked, “Well, what did you think of the boys?”

And Bob said, “Well, I don’t think either of the kids is right for the lead, but I really liked the way those scenes were cut.” Two weeks later, he called me for an interview and hired me for Back to the Future — the beginning of a nine-film relationship with Bob and several awards. None of this would have happened without Jim Clark in my life and career as friend and inspiration.

We continued e-mailing each other regularly until he could no longer e-mail, but I could listen to his Spotify playlists and feel I was sharing something with him as I continued to write him weekly, even when I had very little new to say. And of course, thanks to his wife Laurence, we were able to come to lunch, tea and coffee with him on our visits to London during his last difficult years.

Jim was obviously the best thing that happened to me in my editing career and, most importantly, he was my best friend. I’ll miss him greatly.