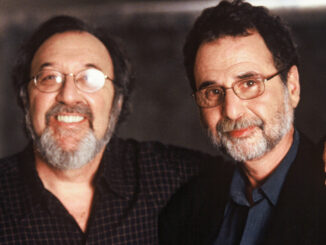

by Scott Essman

“David, you’re the editor, there’s the film; make me a movie. Don’t think about it. Just try everything.”

This advice, offered by a director early in the prolific 45-year editing career of David Saxon, made an impression which stuck with him from then on. Taking the notion one step further, Saxon wrote an article about the myriad possibilities inherent in the process of editing. “Ten shots can be arranged more than three and a half million ways,” he noted, “just by rearranging them, without any trimming. The editor makes an astronomical number of conscious, unconscious, instinctive, and often agonizing decisions, so that he will, like Michaelangelo, find the statue in the block of marble.” This philosophy has led to a distinctive body of work which features three ACE Awards, five additional ACE nominations and an Emmy.

David Saxon was born in Brooklyn and moved to California with his family in 1948 – but not before an overseas experience that helped lead him to his future profession. “I was in the Army in ’44”, he recalled, “and was sent to Belgium, and then to the Ninth Infantry Division in Germany in 1945. In the past I had taken a lot of pictures, so I went to the Army newspaper office, and I said, ‘I’m a photographer!’ I became the photographer for the Ninth Division News. I did Speed Graphic work which used the old flash bulbs. From then on, I used a 35mm Leica.”

When Saxon returned from duty, he went to Cornell University for a year, and then to the College of the Pacific where he received a Bachelor’s Degree in mathematics. “Mathematics was not for me. I enrolled in the Theater Arts Department at UCLA as a graduate student for two years. From there, a job as a cameraman-editor in the early 1950s, doing 16mm Chamber of Commerce films across the South: San Antonio, Shreveport, Texarkana, and in Atlanta, which was their main office.”

Returning to Los Angeles in 1955, Saxon visited a company he had worked for during his UCLA days. “That afternoon, I got a job as a film editor working on TV commercials,” noted Saxon. “and I joined the Editors Guild in 1957. One day a friend called me up and said, ‘I’m working at David Wolper Productions. Would you be interested in doing a film?’ What a question.”

“If nobody tells you what to do, then you have to think, and you give them the benefit of your knowledge, experience, and taste.” – David Saxon

His first experience with legendary producer Wolper was on The Story of a Wrestler in 1962, followed by the immensely successful documentary D-Day and leading to a 16-year career with Wolper’s organization. “It was a very creative time and place,” Saxon said. “I remember the long hours but nobody minded them. There was always something different going on. And it was very friendly – people at Wolper let the other people who were working do their thing, so there was nobody coming in and sitting behind me and saying, ‘Put this here, put this there.’ They wanted the benefit of a person’s skill, so they would look at it, then make the changes. And that’s the way to do it.”

In those days, Saxon fondly described the hands-on nature of his craft. “There were no fancy editing machines-everything was trimmed in,” he recalled. “There were no electronics – we used Moviolas, then the flatbeds. I never liked using a Moviola, particularly with 16mm – it’s a very slow instrument.”

During the 1960s, Wolper had contracts with National Geographic and Saxon edited many documentaries for them. This often led to a personal interest in the films’ subject matter. Over the next two decades, he would produce and edit many more documentaries for Wolper, including Monkeys, Apes and Man, for which he received an Emmy; Strange Creatures of the Night, and Search for the Great Apes, for which he won his first ACE Award.

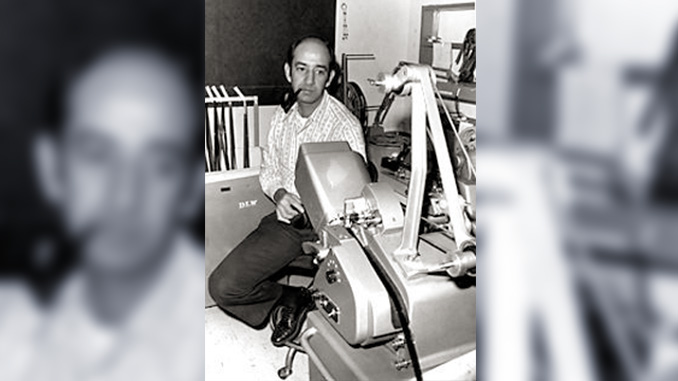

In the early 1960s, using his knowledge of photography, Saxon experimented with a process for creating multiple filmed images without expensive opticals. His intuition led to an unusual solution. “‘Mirrors. I bet that’ll work,'” Saxon thought, “so I had small pieces of a mirror, and put them on a flat board. Then, I set it upright, and using a camera with a zoom lens, I zoomed in on the central image in the mirror and pulled back. Sure enough, all the images that it was reflecting remained exactly in place. If you dollied, everything would change – you wouldn’t retain the same image. So, over a weekend, I built this three-feet-wide device containing 49 mirrors.”

The process came to be called Multi-Vision. Saxon patented it in 1967 and used it for a Nancy Sinatra TV special called Movin’ With Nancy. “It took me about two hours to set it up,” Saxon described. “The advent of the zoom lens allowed it to happen. That’s why I got the patent. I’m sure multiple images were invented long before, but not with a zoom.”

The only type of project Saxon had yet to undertake with the Wolper organization was a feature film. “I had been working at Wolper with director Mel Stuart on many projects, but they were television shows,” he related. “Then, when the decision was made to go ahead and do a feature. I said, ‘Mel, I’d like to cut that feature,’ as I had been an editor for twelve years at that point. He said, ‘Okay, you got it,’ so I cut If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium in 1969. After the success of that film, Saxon, Stuart, and the Wolper organization embarked on a project that would become one of the most beloved children’s films of all time.

“Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory was a marvelous experience,” Saxon said. “Stan Margulies was the producer, and he said, ‘we’re going to go on location and take the department heads with us, but we’re going on a wonderful location. And we’re not going to work six days, we’re going to work five.’ The place was beautiful, outside of Munich, at Bavaria Studios in a town called Gruenwald.”

The company left for Germany in August of 1970, utilizing a German crew and international cast, and returned in December. Despite the fact that he was on location, Saxon had the freedom to first-cut the picture without instruction. “If nobody tells you what to do, then you have to think,” he observed of his work with his Wolper colleagues, “and you give them the benefit of your knowledge, experience, and taste. Of course, the film tells you what to do. You can’t impose yourself on the film.”

“I remember the long hours but nobody minded them. There was always something different going on. And it was very friendly” – David Saxon

In the 1970s and ’80s, Saxon continued to work actively in documentaries and television shows. He won additional ACE awards for an episode of Hill Street Blues and for editing a film that he produced, The Living Sands of Namib in 1978. Saxon also had the experience of using the Montage, one of the first non-linear electronic editing systems, on a three-hour 1988 TV special about Aristotle Onassis, called The Richest Man in the World. “I had the entire three-hour show cut the day after they finished shooting,” he said. “The show was more than assembled, it was cut. I could work that fast on the Montage, even though I was a film editor. With what they’re doing now, you can try 20 different things in a matter of minutes.”

In the early 1990s, Saxon was called out of retirement to edit three documentaries for the Cousteau Society. “I walked into a room full of film – five hundred boxes!” he remembers. “There had been four undersea expeditions for one film alone, The Great White Shark, Lonely Lord of the Sea. I worked for Cousteau for two years.”

Far from being inactive, Saxon still indulges in his first love. “I never stopped picture taking,” he said. “And now, I will not go on a trip unless I can take pictures. What most fascinates me is shooting still photographs in 3-D for viewing with a stereoscope, a process that was invented in the 1800s.”

Looking back on a fulfilling career, David Saxon reflected on his affinity for editing. “I get bored easily, but in editing, you never have to do the same thing twice,” he said. “With any piece of art, you have to make that decision – how do I do this? I love problem solving. That is the essence of editing.”