by Tom White • portraits by Sarah Shatz

The documentary form has been around since the beginning of cinema, and over the past 15 years, pundits have bruited this past decade and a half as “The Golden Age of Documentaries.” No matter the platform — theatrical, television or online — documentary has transformed itself from the margins to the mainstream as a galvanizing and provocative art form.

So given that, why are there relatively few documentary editors among the Editors Guild rank and file? Well, despite the dramatic growth in popularity, the documentary process is a decidedly low- budget one, one that calls for economy in personnel and versatility in skill sets. Two- or even one-person production crews are not unusual, not only to keep costs down, but — when making docs in dangerous, war-torn areas, for example — for safety considerations as well. And in the post- production phase, too, a skeleton crew is often the rule. What’s more, fundraising is a constant through-line in the documentary process, and it’s not unusual for documentary makers to spend seven years or more on a project.

Chalk it up to the volatility or capriciousness of the documentary career, but there just aren’t many doc editors who are also MPEG members. However, CineMontage managed to track down three, all of whom toggle between docs and feature narratives.

Deborah Peretz started out in features, working in editorial departments on such films as The Untouchables (1987) and Black Rain (1989). Over the past 20 years, she has edited many PBS documentaries, for the venerable strands American Experience and American Masters. Peretz has earned a Primetime Emmy Award, two Emmy nominations and an ACE Eddie Award.

Phillip Schopper also started out in features, but a bulk of his work throughout his editing career has been in documentary. Within the doc genre, he has edited both archive and vérité work, as well as non-fiction series and one-offs, and a lion’s share of his films have aired on HBO. Complementing his prowess in the editing room, Schopper also has five directing credits on his résumé.

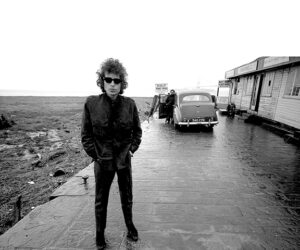

David Tedeschi has had the good fortune of editing docs for one director over the past several years: Martin Scorsese. Highlighted by the monumental epics No Direction Home: Bob Dylan (2005) for PBS’ American Masters, and George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011) for HBO, Tedeschi’s collaborations with Scorsese have earned him two Primetime Emmy nominations and one ACE Eddie nod. He’s currently at work on a fiction series for HBO, helmed by Scorsese, about the rock music scene in 1970s New York.

All three editors are based in New York. CineMontage spoke to them about being Guild members, how their work in fiction and non-fiction serve each other in their respective processes.

WORKING UNION

Peretz, Schopper and Tedeschi have all been Guild members for at least 15 years, and all joined when they were hired to cut narrative features. Schopper, the longest- running MPEG member of the trio, at more than three decades, had been editing independent work before he was asked to work on the 1981 film Reds — but he didn’t join just then.

“I was fairly fully engulfed in the world of studio feature post-production and was working more or less alongside idols like Dede Allen and Craig McKay,” Schopper recalls. “It was wonderful, but it still wasn’t a situation that opened a door to Guild feature editing for me. However, that work led me to Marlo Thomas and a project for ABC. She was producing through her own company. The show had been completed, but was in need of a complete editorial makeover. I think because of my unconventional entry into the world of editing and the kinds of projects I had edited and directed, I was the perfect person to rethink and remake her project. So, a year or so later, when she had a TV feature for CBS, she insisted that I be the editor. It was an IATSE production, so it required my joining the union. I was elated. I happily paid the initiation fees — and I think scale then was only around $675 a week — because it meant I was now free to be considered for union work.”

Needless to say, the scale is considerably higher these days, and the health benefits are a major factor in the three editors working union. “Having good health coverage when starting a family and raising children has been a huge benefit,” Peretz maintains. “Of course, having a contract that insures certain protections like overtime and holiday pay has been a boon as well. Only once, early on, was I in a situation where I needed the Guild

to intervene in a dispute about pay. After several months, they were able to collect for the crew — something we would not likely have been able to accomplish on our own.”

Before Tedeschi joined the union, “There was this sense that you had to work insane hours all the time in order to get the job done,” he explains. “And for the most part, it didn’t pay overtime. Now I still work insane hours, but the producers are more cognizant of it because they have to pay for it.”

That said, finding any work editing documentaries is difficult, but finding work on a union doc is daunting. “You have to hold strong,” Tedeschi says. “You have to hold the job as union if they want to work with you. Not everyone is in that position, and it’s not the easiest thing to do. But that’s the ideal.”

“I wish there was more union work,” Peretz adds. “I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have worked for producers committed to signing with the union, and I’m very appreciative. I realize that it’s not always so easy for them. One producer I worked with — Sasha Reuther — was a first- time filmmaker with a small budget. His film, Brothers on the Line, was about his grandfather and uncles, their roles in the growth of the United Automobile Workers and their involvement with the social justice movement. Given the subject matter, Sasha knew from the start that he wanted to work with a union crew and was willing to assume the additional cost. But that is unfortunately unusual. I think a lot of people just assume that it will be too costly or that the paperwork will be too onerous.

“If there was more union work, then more editors and assistants would be willing to join,” she continues. “And if more people were union members, then producers would feel a greater need to work with union crews. Outreach, as Sasha has suggested, is also important so that producers are aware that the Guild is willing to work with them.”

Schopper expounds on that point: “Although the Guild really works hard to customize its deals and tries to work with both producer and editor to structure something that will work, you can’t get around the fact that a union contract still adds extra dollars to the budget, and films aren’t cheap to begin with. But we editors should try to push for a union job every time. That’s almost impossible to do if you are starting out or are a new editor with a slim résumé, but if the producer wants you, you should try to make it happen.

“I’ve met several really good editors who don’t join the Guild because they are afraid they will be passed over in favor of a non-union editor,” Schopper continues. “And when I point out that the union has nothing against working a non-union job, they say, ‘Yeah, but meanwhile I’m paying all those dues but not getting the benefits.’ Well, one of the great things about the Guild is that you can go on withdrawal at any time. If you do that [and not work in a capacity represented by the Guild], you can avoid the dues and still come back when you have an opportunity to work or turn a non-union job into a union one.”

A NEW YORK STATE OF MIND

All three of these editors hail from New York, even though Los Angeles, San Francisco, Boston and Chicago have all proven their mettle as vital centers for documentary production. But New Yorkers seem to capture that Guild member/doc- maker sweet spot.

“Traditionally, there are many more docs made here on the East Coast than on the West Coast,” Schopper says. “There was a time here years ago when there were more large companies doing documentary production, and there was a bigger union presence — but there were also fewer documentaries. Also, there weren’t film schools everywhere then and editors grew from within the industry and were thus union.”

“I just think there is more work for documentary editors in New York City, period,” Tedeschi opines. “It does seem that New York has been a real center consistently for making documentaries in a way that hasn’t been necessarily consistent for other parts of the industry.”

DOING THE NON-FICTION/FICTION SHUFFLE

Peretz, Schopper and Tedeschi flex their editorial muscles in fiction as well as non-fiction, and they all find common ground between the two. In fact, working back and forth has served to strengthen their craft and artistry.

“There’s a lot of commonality between features and docs,” Peretz asserts. “Both are about storytelling and require building a dramatic arc, character development, finding the emotional essence in scenes and creating pacing, rhythm and musicality in the cutting. Where it differs is that documentaries are often more or less written in the cutting room. This can be incredibly exciting — discovering the film in a mountain of material alongside the director. It’s also incredibly challenging and stressful at times, knowing there’s a film in there somewhere, but what exactly is it?

“There have definitely been days when I longed for a script with a clear beginning, middle and end,” she adds. “Or times I’ve been cutting a vérité scene knowing just where I want to be for a certain moment when, alas, the DP was elsewhere! And I’m wishing I had the coverage I would have had on a feature. But that’s all part of the challenge — and sometimes the fun of it.”

Photo by Bob Daemmrich

“The biggest challenge is that producers don’t necessarily understand why you’d want to go back and forth between the two,” Tedeschi notes. “And sometimes you’ll have to explain yourself. For me, it’s different parts of my brain, and I love both of them. People often say to me, depending on their prejudices, ‘Well, isn’t documentary — or narrative — editing a more skilled profession?’ But to me they’re both thrilling. They offer different kinds of challenges.”

According to Tedeschi, the challenges in a documentary are generally that “you have fewer resources and there’s no script. But the thrill of it is, you put together the story and the structure. In the case of narrative, aside from the fact that it has more resources, in terms of classic editing — color, sound, composition — you’re able to have a very refined piece of filmmaking, and I find that thrilling as well.”

For his part, Schopper tries to look at documentaries and features as though there is no difference at all. “They both are movies and they both must satisfy a viewer; they must tell a clear and compelling story,” he stresses. “A documentary is a dismal failure if it isn’t first a gratifying audience experience. It might have something very important to impart, but it still has to compel us. Otherwise, it may as well be a school lesson.”

And while Tedeschi cites the availability of resources to narrative editors as a positive, Schopper counters that a comparative scarcity of resources for doc editors can be an advantage. “The documentary editor has many more tools at his disposal — or perhaps I should say at his brain’s disposal — that many feature picture editors may not,” he contends. “And that’s simply because they haven’t had to acquire them out of necessity. On a big feature, so much stuff can be left to other departments, whereas on a documentary, the editor is frequently his own one-man army. On a documentary, you aren’t working with material that’s been thought out and scripted and practically visualized before it came to you; ‘coverage,’ more often than not, has to be invented out of thin air.”

To be a successful documentary editor, according to Schopper, “You really have to become a problem-solver many times over — and sometimes the solutions lay in learning to manipulate the sound or master a variety of effects, and learn that ‘effects’ can be a tool to solve problems, not just to generate the fantastic or sensational. You simply must develop a decent arsenal of tools to solve what may appear to be insoluble. And that knowledge serves very well in narrative too. When scenes, lines or shots don’t work, it’s good to have a brain that’s been formed from thinking outside the box. Documentaries rarely come in boxes.”

“Being a documentary editor taught me to be resourceful,” Tedeschi agrees. “When I started out, people were shooting film. There was a culture of studying what you have and using it to the best of its ability — which all good editors do, but when you’re young, it’s more in the forefront.”

In his early narrative work, Tedeschi says he was hired because he had a documentary background. “I worked on The Shield — it was a narrative series but it had a documentary feel,” he says. “I had done narrative before, but I think the producers were also attracted to the fact that I had done gritty New York documentaries. Piñero was that way too because it had a very low-budget feel. It was a gritty, New York story set in the ’70s, and a lot of it was handheld. It was a scripted feature but the final film structurally did not resemble the script.”

“Having a good feel for what will make a satisfying experience in terms of a flow of emotions or moods is often key to how to make it a good film,” concludes Schopper. “Whatever you do, it still has to work as a ‘movie.’”