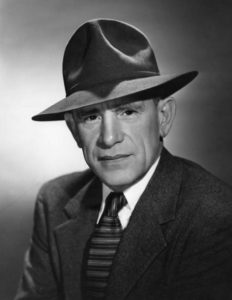

Daniel Mandell (1895-1987)

In the rarified group of only four triple-Oscar-winning picture editors, Daniel Mandell’s wins were for The Pride of the Yankees (1942), The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and The Apartment (1960). He actually began his career in show business as an acrobat in his family’s troupe, “The Flying Mandells,” also known as “The Mandell Brothers.” He toured the country with the Ringling Bros. Circus before switching to vaudeville and performing four shows a day.

After fighting in World War I, Mandell followed the advice of a childhood friend who was working as an editor at MGM and decided to try his luck in the film industry. His first official editing credit was on The Matchmaker in 1920. He worked at various studios, including stints at Fox, Universal, Pathé, RKO and Warner Bros., before joining Samuel Goldwyn Studios. Mandell’s work at Goldwyn from 1935 to the early 1940s included Dodsworth (1936), Dead End (1937), Wuthering Heights (1939) and The Little Foxes (1941).

In 1951, Mandell commented to Howard McClay in The Los Angeles Daily News that his background as an acrobat benefited him as an editor because it enabled him to develop a sense of how audiences react. “Timing was the most important factor in this respect,” he told McClay, and said that he learned to figure out what people laughed at—and didn’t.

Selise Eiseman

Anne Bauchens (1882-1967)

Anne Bauchens was the first woman to win a Film Editing Oscar. But her artistry was devoted to one man, one who symbolized Hollywood: Cecil B. DeMille. Though she edited 63 films, of which over 40 were De Mille movies, all of her Academy Award nominations were for his productions, Cleopatra (1934), The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), The Ten Commandments(1956), and her Oscar-winner, Northwest Mounted Police (1940). She was with him from almost his beginnings in directing to his retirement in 1956. Then she retired also.

DeMille resisted editors, so he was lucky to have Bauchens, who was an aspiring actress when he met her in 1912. She became his negative cutter and script girl before being promoted to editor on Carmen in 1915. The doyenne of Hollywood film editors, Margaret Booth, told film historian Kevin Brownlow (who produced a documentary on DeMille) that Bauchens would have been a better editor without DeMille. “DeMille was a bad editor, I thought, and made her look like a bad editor,” Booth said. “But she had to put up with him — which was something.” For Bauchens’ tireless efforts, she was nicknamed “Trojan Annie” by her colleagues because the DeMille productions were astonishing epics teeming with elaborate sets and ornate set direction, cast-of-thousands crowd scenes and disasters. All of this required precision matching by the editor of the glass and matte shots, as well as the action scenes, in those pre-digital days.

Kevin Lewis

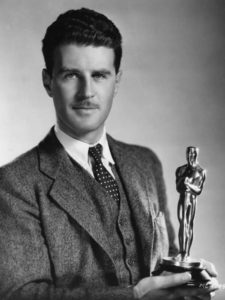

Douglas Shearer (1899-1971)

Douglas Shearer was the organizer of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s sound department in 1927 and the director of its technical research until his retirement in 1968. He entered the film industry by accident when he came down from Montreal to visit his actress sister, Norma, who was already an important MGM star. With a background in engineering, he became interested in adding sound to her latest film, Slaves of Fashion (1925). He was hired as an assistant cameraman, but was soon inventing trick camera effects.

Shearer and the MGM sound department received the first Academy Award in 1929-30 for Sound Recording for The Big House (1930). The all-time multiple-Academy Award-winning champ (14!) went on to win four others in 1935 (Naughty Marietta), 1936 (San Francisco), 1940 (Strike Up the Band) and 1951 (The Great Caruso). In addition, he received two Special Effects Oscars (Sound/Audible) — for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944) and Green Dolphin Street (1947). Also, he received seven Scientific and Technical Awards. Film historians have said that Shearer was to MGM in Sound what Cedric Gibbons was to MGM in Art Direction. Los Angeles Times film critic Kevin Thomas mentions in Shearer’s obituary that he was as familiar as Leo the Lion’s roar, and that the films on which he worked had a “kind of subliminal guarantee that there was a continuity and permanence in the pleasurable escapism of going to the movies, especially MGM’s glossy productions.”

Selise Eiseman

Barbara McLean (1903-1996)

Barbara McLean was a superior editor throughout the Golden Age of Hollywood, but she was something more: a true leader who became head of the editing division at 20th Century-Fox in 1949. For the next 20 years, while Fox dealt with expanding screens (Cinemascope) but shrinking audiences (television), McLean employed editing teams which were among the most respected in the industry.

Studio head and producer Darryl F. Zanuck relied on McLean’s artistic judgment and her wisdom about people. He discovered her editing films at United Artists in 1933, which was also the company that released his Twentieth Century Pictures. When Fox Film Corporation merged with Twentieth Century in 1935, Zanuck hired her and she became the main film editor for director Henry King, Zanuck’s favorite director after John Ford.

McLean edited almost 30 films — out of her 62 credits — for King, winning her only Oscar for his Wilson (1944). She was nominated six other times, three of which were for King films: Lloyds of London (1936), Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938) and The Song of Bernadette(1943). Her other nods were for Les Miserables (1935, Richard Boleslawski), The Rains Came (1939, Clarence Brown) and All About Eve (1950, Joseph L. Mankiewicz).

Arguably, she should have been nominated for The Robe (1953), the first film in Cinemascope, for which McLean had to develop an unprecedented style of editing for this widescreen format.

Kevin Lewis

John Paul Livadary (1896-1987)

Photo: Bison Archives

John Paul Livadary was a motion picture sound pioneer who began at Columbia Pictures in 1928 — a year after The Jazz Singer was filmed. He won three Oscars for Sound Recording: One Night of Love (1934) as sound director of Columbia’s sound department, The Jolson Story (1946) and From Here to Eternity (1953). Livadary was also recognized by the Academy between 1937 and 1954 with four Scientific and Technical Awards for the patents he held on magnetic tape and multi-track recording systems. He was known as the technician’s technician.

Originally moving to the United States after studying medicine in Greece, he served in the Army and then attended MIT, from which he graduated with advanced degrees in electrical engineering and mathematics. Livadary went to work for Bell Laboratories for four years, spent six-months at Paramount Pictures and then began his long tenure at Columbia.

His work on One Night of Love innovated the way opera arias were recorded for motion pictures. Livadary and his assistants put the arias on “hill and dale” records, so called because the grooves are cut in different vertical depth instead of side by side. In the 1933 Motion Picture Almanac, Livadary stated, “Sound perspective is highly important and is a comparatively recent improvement in motion pictures… Such perspective makes the voice have just the right volume and quality for whatever distance the player may be from the camera.”

Selise Eiseman