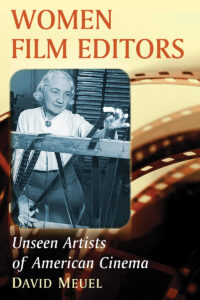

Women Film Editors: Unseen Artists of American Cinema

by David Meuel

McFarland & Company

Paperback, 216 pages, $35.00

ISBN #978-1-4766-6294-7

by Betsy A. McLane

“Great film editing begins with great pictures,” said Barbara “Bobbie” McLean in a 1977 interview in Film Comment magazine. She could make such a gracious statement with authority at that point, after cutting for more than 60 years, beginning as a schoolgirl patching together release prints in her father’s Patterson, New Jersey film laboratory.

McLean’s decades editing such films as the early Mary Pickford talkie Coquette (Sam Taylor, 1929), Henry King’s Twelve O’Clock High (1949) and The Gunfighter (1950), and Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950) — as well as the challenges of editing the first film shot in Cinemascope, The Robe (Henry Koster, 1953) — provide credits enough. It is the seven Oscar nominations, recognition as one of the first two recipients of the American Cinema Editors’ Lifetime Achievement Award and, chiefly, her position as editorial supervisor, trusted confidant and right-hand woman to Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century-Fox that leads author David Meuel to say that McLean could quite well be “the top Hollywood film editor of her era.” And he has much more to add.

McLean’s decades editing such films as the early Mary Pickford talkie Coquette (Sam Taylor, 1929), Henry King’s Twelve O’Clock High (1949) and The Gunfighter (1950), and Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950) — as well as the challenges of editing the first film shot in Cinemascope, The Robe (Henry Koster, 1953) — provide credits enough. It is the seven Oscar nominations, recognition as one of the first two recipients of the American Cinema Editors’ Lifetime Achievement Award and, chiefly, her position as editorial supervisor, trusted confidant and right-hand woman to Darryl F. Zanuck at 20th Century-Fox that leads author David Meuel to say that McLean could quite well be “the top Hollywood film editor of her era.” And he has much more to add.

Although largely invisible to the public, within the profession women picture editors like McLean and Margaret Booth, Verna Fields, Dede Allen, ACE, and Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE, are regarded as pre-eminent. Women Film Editors: Unseen Artists of the American Cinema gives each her due and also illuminates the contributions of other important women editors, some of whom may be unfamiliar even to Hollywood history cognoscenti. Meuel profiles nine in some depth; in addition to the five above, these include Anne Bauchens (who appears on the book’s cover), Viola Lawrence, Dorothy Spencer and Anne V. Coates, ACE. Nine others are afforded briefer, but serious mention: Rose Smith, Dorothy Arzner, Blanche Sewell, Adrienne Fazan, Marcia Lucas, Carole Littleton, ACE, Susan E. Morse, ACE, Lisa Fruchtman and Sally Menke, ACE. As the author is quick to note, there are others, and his modest volume only begins to explore the subject.

There is criminally little research and writing on the often astounding careers of female editors. The same might well be said about many of their male counterparts, since most editors do tend to be unseen artists. Yet men came to dominate the field by the late 1920s and continue that hegemony today. Recent historians’ efforts have reclaimed some attention for many female filmmakers, especially in the area of silent film studies. The Women Film Pioneers Project at Columbia University (wfpp.cdrs.columbia.edu) is one of the best. Through efforts like this it is now well known that many women played central roles in the founding of the film industry.

Proportionately, there were more women employed in every aspect of the business during its first two decades than at any time since. It is also understood that as the companies consolidated, as larger amounts of money were involved, as film work became a more prestigious occupation, and eventually as the assembly-line practices of the studio system were codified, women were discouraged from pursuing editing, if not actually pushed out of jobs.

Lawrence, a full-fledged editor for D.W. Griffith at Vitagraph by 1915, applauded as editor of Howard Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and derided as a destroyer of Orson Welles’ director’s cut of The Lady from Shanghai (1947), is quoted by Meuel as saying of her husband Frank (who taught her editing and supervised editors at Paramount in the 1920s), “He just hated them [women]… If any of the girls were cutting — if they did get the chance to cut — he’d put them right back as assistants.” That some women thrived for decades and others managed to begin and build careers in this environment is notable, and Meuel clearly proclaims his admiration as he examines the reasons for their successes.

For his nine main subjects, the author provides a chronological account of their beginnings and major films, both successful and mediocre. He follows with a closer reading of one film that he considers exemplary in each one’s oeuvre. For Lawrence, this is what many consider the masterpiece collaboration among director Nicholas Ray, writer Andrew Solt and actors Humphrey Bogart and Gloria Grahame: In a Lonely Place (1950). As he does with every editor, Meuel credits the chief creative impulse to the director, and acknowledges the contribution of everyone involved, while emphasizing the unique artistry that the editor brings. In this case, that is Lawrence’s handling of the many close-ups and two-shots of Bogart and Grahame. Meuel points out that as Bogart and Grahame’s affair begins to unravel, the close-ups of the couple “become more frequent, more complicated, more revealing. Often, they betray the words the two lovers are sharing with each other.” Such sequences prove Lawrence’s statement, “To me, the eyes are everything.”

Bison Archives

For contemporary subject Littleton, an Oscar nominee for her work on Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), the author chooses to highlight Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart (1984), citing her “Touch of the Poet.” With Schoonmaker, Martin Scorsese’s collaborator for 35 years, the film analyzed is of course Raging Bull (1980), which members of the Editors Guild voted as the Best Edited Motion Picture of all time in the issue of CineMontage that celebrated the Guild’s 75th anniversary in 2012. Schoonmaker, who won an Oscar for editing the film, at first turned down the picture, because she was not a member of the Guild, but she became one, and history was made.

Meuel exemplifies Bauchens’ work with Cleopatra (1934), for which she was nominated for an Oscar in the first year that editing awards were given. Bauchens began a 40-year, 39-film partnership with Cecil DeMille in 1917 when she was already 30 years old, along the way earning the nickname “Trojan Annie” for her legendary stamina. She cut, with DeMille at her side, every one of the films he made between the late teens and the late 1950s. She was also usually on set and, because of the huge scope of a DeMille epic, they regularly worked 16 to 18 hours at a stretch in the 1920s, cutting back to 10-to-14-hour days in the 1950s when they were both in their 70s. Making The Ten Commandments (1956), DeMille sometimes used as many as 12 cameras in a scene and shot over 100,000 feet in a picture that also required exact matching with special effects matte shots.

The longevity, varied experiences, aesthetic contributions and, in some cases, sheer Hollywood power held by the women Meuel profiles make their relative obscurity a serious oversight in American film history. This book is a step in remedying that problem. It is an easy read, one that both film professionals and the public can enjoy. Many of the facts are footnoted and a generous bibliography demonstrates Meuel’s attention to detail, although he repeats some stories that may be more Hollywood legend than truth.

For example, was Welles’ original cut of the mirrors scene in The Lady From Shanghai actually 20 minutes long as opposed to Lawrence’s two minutes? We may never know, since Columbia Pictures boss Harry Cohn ordered much of Welles’ footage destroyed. The difference between legend and fact can be impossible to distinguish, especially since often these editors were longtime loyal employees who never sought attention outside their studio gates, nor beyond the realm of the male directors with whom they worked.

Women Film Editors is to be applauded as an admirable contribution on its own, and as an invitation to others to continue investigation into an intriguing subject.