Stories by Michael Kunkes • photo by Gregory Schwartz

Jean-Luc Godard was fond of saying, “A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end…but not necessarily in that order.” What was true for the French Nouvelle Vague easily applies to the production, if not the final product of The Polar Express.

The Castle Rock Entertainment presentation and Warner Brothers-distributed holiday adventure was directed by Robert Zemeckis, stars Tom Hanks in multiple roles and is based on the beloved and Caldecott Medal-winning children’s book by Chris Van Allsburg.

Volumes have been written––and deservedly so––about this groundbreaking film, which debuted a next-generation, custom-created motion capture system dubbed “performance capture,” as well as about the visual effects team at Sony Pictures Imageworks (SPI). Of course, it was all driven by the vision and storytelling expertise of director Zemeckis and co-executive producer Hanks.

So why, four months after the film’s release, and following a general snubbing by both Hollywood at large and even the animation industry’s own Annie Awards show, are we talking about The Polar Express? Quite simply, almost nothing has been said about the editorial process on this film, which represents the official big-studio start of a new era in what can be called “nonlinear production.”

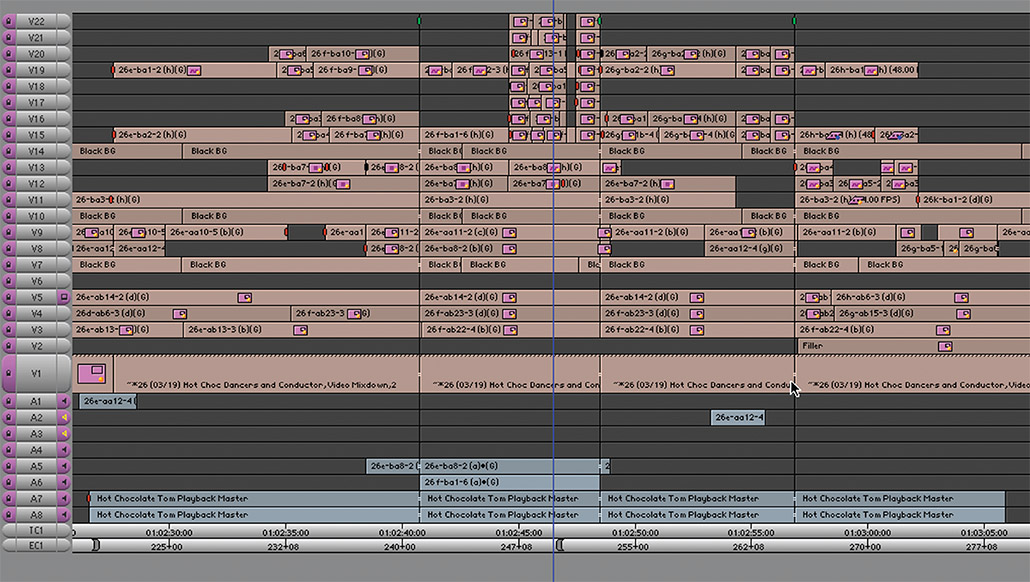

Multiple creative processes, including editing, storyboarding, writing and designing, were occurring simultaneously, and continued to run throughout the two-and-a-half-year production period, while technicians were busy scanning, recording and rendering. This full integration of digital tools into the production process has led to the invention of countless untested procedures––improvised or extant––creating a fusion of production and post that may not be the complete wave of the future, but is certainly here now and cannot be ignored.

Editors who have lived on the “edge of experience” with digital technology for nearly two years are uniquely poised in this new age to sort out the vast numbers of technical issues––large and small––relating to tracking vast amounts of information, budget considerations and, of course, storytelling.

Tracking the more than multiple terabytes of data produced for The Polar Express was no doubt a Herculean task, but that is a job with which editors are well versed. It was arriving at the procedures that proved to be the tricky part.

The work of two very talented professionals, Orlando Duenas and Jeremiah O’Driscoll—both of whom make their debut as editors on this film—and a team of dedicated assistants made sense out of the mountain of storage, helped invent countless new procedures and brought order out of chaos at every step of the way. In so doing, they never lost sight of what they were there to do: Preserve the look of Van Allsburg’s illustrations, which ultimately was the only artistic vision that mattered.

“They both have a fantastic grasp of the art form,” commented Zemeckis about Duenas and O’Driscoll. “And they’re magnificent in the way they’re able to think cinematically.”

“For many years the collaboration between myself and Bob and Jeremiah and Orlando was destined to happen,” added the film’s producer, Steve Starkey. “As we explore this new technology, both Jeremiah and Orlando have been instrumental in paving the way that films will be edited in the future. In this process, typical film production is much more integrated with post-production and it becomes more of a filmmaking process.”

The Polar Express is a misunderstood film. Traditional 2-D and 3-D character animators sneer at performance/motion capture because they feel it undermines their art, and live action fans don’t understand why it wasn’t all animated or all live action. The fact is that The Polar Express is a beacon––a herald of new technology, new methodologies and especially, new opportunities.

What follows is an overview of how the members of the editorial team re-defined their jobs, found new outlets for their existing skills, and gained entry to a world that has preceded and eluded them. This story, and others to come, will provide a glimpse into Hollywood’s future––and post-production’s present.

Orlando Duenas

From his earliest days in film, it was clear that Orlando Duenas was the perfect person to deal with the thousands of details required to support the storytelling issues that came up during the making of The Polar Express.

In 1989, he was assisting Seattle’s only film editor, Pat Barber, who had purchased a very early version of the Avid. “ Five years before the Avid caught on in features, we used to videotape the dailies of low-budget features straight off the KEM with the counters showing, digitize from those tapes and use the Avid to get the films into rough cut, then use the counters to conform the work print and finish cutting the film. So I have often found myself in the position of inventor, with a long history of hybrid procedures.”

Duenas began working with Robert Zemeckis’ team on Contact in 1997, and first met editor Arthur Schmidt and Jeremiah O’Driscoll when they joined the editorial staff of Chain Reaction in 1996. Like everyone else on the crew, he knew exactly what needed to be done to accomplish each step, but not how he wanted to do it. “The folks at SPI knew what they needed to conform the performances, but the level of change and experimentation with which we presented them was unexpected,” he says. “However, from an editorial standpoint, the most important thing for us was to present Bob with the most flexible and thereby creative way of working.”

Duenas feels that in future shows of this type, certain issues will have to be resolved.

Early in production, Duenas worked extensively on cutting together the performance assemblies (based on Zemeckis’ selected mocap takes), which he then recut with the director and sent on to SPI for integration of the selected performances with other video layers. “Performance assemblies can become a very mind-boggling process, depending on the complexity of the scene,” he explains. “You start with the character who is driving the scene, cut together his performance, and then add other characters to the mix, always keeping in mind who will probably be on camera and when.”

Since he was editing multiple characters before any coverage was actually created beyond the wildly emoting mocap images, Duenas had to throw out some rules right at the beginning. “Movie actors play to a camera, but in a mocap scenario, they don’t know where the camera is ultimately going to be,” he says. “You keep yourself out of trouble by not cutting too tightly and lining up the performances as best you can, even if you have to force it.”

For Duenas, it soon became clear that his role in the show was going to be one of jumping the huge number of technical hurdles and interfacing with SPI. “Jeremiah and I knew that one of us was going to have to be on top of insuring that the integrated material coming back from Sony was meeting our intentions, and that the thousands of requests for new shots and edited performance assemblies was being done correctly,” he relates. “That job fell to me, while Jeremiah took charge of the creative aspects of performance.”

Day to day discussions with SPI consisted in large part of the minutia of performance assembly alterations, Maya file edits, layout requests, background character tiles and three different stages of shot review. “Since we turned over different sequences at different times, we were always having the same types of discussions,” Duenas explains. “Initial turnovers involved discussing Bob’s expectations for the sequence as a whole, as well as individual shot notes, but no line-ups. More complex were the budgetary reviews where we would talk about compromises on individual shots, and final turnover talks covered counts and revisions. It pretty much killed our social lives for over two years.”

“Performance assemblies can become a very mind-boggling process, depending on the complexity of the scene.” – Orlando Duenas

The integrated scenes were delivered back to Duenas in the form of a “sync check,” which consisted of the rudimentary low-resolution place-holding characters in a mock-up of the environment, which Zemeckis called “Michelin Men.” These were synched up to the previously turned over performance assemblies and minutely checked for alternations made by SPI during the integration process.

“Sometimes modifications were necessary and we needed to work with the integrators to ensure that Bob was getting what he wanted,” says Duenas. “Usually, a couple of phone calls would be needed before a sync check was deemed okay to go to the next phase.”

Dailies were finally shot in what was called the layout process, which refers to the scene as it exists in its 3-D environment—including characters, sets, props, camera, backgrounds and secondary characters; in short, everything.

Two layout processes were employed, both under Zemeckis’ direct supervision: Maya layout, where direct camera moves could be quickly keyframed, and Filmbox layout, which refined the camera moves via the “wheels” interface [see O’Driscoll story]. “One problem I had with layout was that there was no representation of the actors’ facial performance available during shooting, but Bob’s familiarity with the performance assemblies saved us,” Duenas confesses. “Let’s say you want the camera to stop pushing in at the moment the hero realizes he’s been duped. If you don’t have the timing in your head, you have a problem.”

The original layout plan called for shooting dailies via Filmbox, but any editing or manipulation of the original integration during layout was extremely time-consuming. “We found it better to shoot dailies in Maya, lock down the cut, then have final camera––or FINCAM––applied to only specific frame counts,” he says.

Creating a constantly evolving process led to a lot of “seat of your pants” moments for Duenas: “We would decide what we felt were the required aspects of turnovers; SPI would then come back with particular requests or rejections, and then we would mutually pound out a working solution. Sometimes the road became rough, but for the good of the picture as well as the process, most battles were worth fighting.

The only way to keep sync on this show was to never get out of sync, period.

“Right from the start, we decided to use a common time-of-day or ‘house’ time code,” he continues, “which was mastered in the video department, then sent to the motion capture department and encoded into the data. It was also sent to the sound department to be used as the DAT master timecode. This time code went to all videotapes, sound masters and to the performance capture computers, so that all EDLs would reflect a common time code.”

This was a help in some areas, but not always accessible in others, especially in regards to sync, where the problems were many, and the solutions not always elegant.

“The first thing to note,” says Duenas, “is that ‘sync’ on our show referred to both video and audio; that is, video being in sync with the performance capture data, and of course audio with both. The main problem was trying to sync up the constant flow of dailies and revised shots. We had no timecode burn-ins for aligning video and audio to shots, and no paperwork either.”

As an example of this, whenever edits were made in layout to the original performance assemblies, all sync reference was lost. One possible solution to the sync problem that Duenas came up with was to create Quicktime movies of the performance assemblies, that could be synched up in Maya layout to determine certain performance to camera issues. Then, in rendering, he would include the Quicktime panel in the Avid’s matte area as a reference for sync. “Since we were cutting anamorphic, we had a lot of area above and below the picture, where we traditionally placed the floating head in the ‘Michelen Man’ shots,” he said. “Placing the Quicktime panel in that area gave us a reference cut so you could tell how the original mocap material synched up to the layout material.” Since this was a solution arrived at late in the process, it served mainly as an academic exercise and as a lesson for future productions.

There was also a problem early on in the show when the integration came back from SPI and Duenas found that the time code was five or six frames off from the video time code. “Since most shots were based on known performance assemblies or specific edits to known performance assemblies, we could ballpark it, and then it essentially became an eye-matching job,” he says. “Luckily, we could revise sync any way we wanted, right up to final turnover.”

“If you don’t have the timing in your head, you have a problem.” – Orlando Duenas

Ultimately, he explains, the only way to keep sync on this show was to never get out of sync, period. Describing the typical scenario, Duenas says, “The syncher must be in perfect sync with the sync check, a painstaking process of checking every character by eye, at every edit. Then, as shots come in, we utilize this new syncher to sync up the video and audio tracks to the new shot using the layout frame counter. This works okay––until edits are made in the Maya file, and you get the cryptic note regarding the change. Now, try this with 20 dailies a night from four different sequences for 12 months straight. That’s why sync was the cotter pin that kept this entire train on the tracks.”

Duenas feels that in future shows of this type, certain issues will have to be resolved. “There still is no way to track sync via timecode, or any other reference data,” he says. “For example, say Bob wanted to delete 24 frames from a pause in a character’s performance. Easily done, but getting that information to editorial proved awkward and cumbersome. The layout operator provided a handwritten change note, but making changes in layout is not handled like making a change on film. They don’t have the time to track it that closely, and in order to make something work in layout, there are sometimes multiple edits to multiple characters at various points in the timeline. Try to get a beleaguered layout guy to track that with the director breathing down his neck!

“So, yes,” he continues, “a system of assemble and change notes will need to be devised, and some kind of burn-in referencing of the original timecode of elements is really needed, for obvious reasons.”

Although Duenas’ major role was driving the technical process, he was never out of the creative loop. “Jeremiah would consistently stick his head in my door and say, ‘Watch this,’ and I would contribute my two cents,” he recalls. “During turnover meetings, Bob maintained an open forum for commentary that allowed me to suggest and later execute revisions. And since we were constantly manipulating the video plates in terms of the performance––and also choosing all the surrounding extra Kid and Elf plates––it was a very fulfilling project creatively.”

“Sometimes the road became rough, but for the good of the picture as well as the process, most battles were worth fighting.” – Orlando Duenas

But just as Moby Dick was “a monstrous big whale, aye, but a whale, no more,” Duenas says, “The Polar Express was shot as a ‘real’ movie, and was edited as a ‘real’ movie, only with a lot more picture tracks. One of the coolest things about this process is the way you can revisit shots, pretty much all the way to turnover.”

As he looks forward to his new career as a full editor, Duenas reflects, “Helping to unleash this new technology on the unsuspecting public was exciting and a little bit scary, but I don’t want to end up working only on groundbreaking effects projects. Two and a half years…It’s far too exhausting.”

Jeremiah O’Driscoll

About his role on The Polar Express, Jeremiah O’Driscoll is very specific. “Having worked with editor Arthur Schmidt for so long on a number of Bob Zemeckis’ pictures, I recognized early on that my job was to be the caretaker and preserver of the original performances,” he says. “At every phase, I was the one who insisted that if what is happening on Tom Hanks’ face isn’t driving his character, we needed to get back to the original performance. I always had to keep in my mind Tom’s original inspiration and Bob’s vision for the show and speak up when something didn’t ring true. Because if we lost Tom’s original performance, then we might just as well have made a traditional animated film from the start.”

“I constantly judged who was driving the scene at any given moment and fit the other performance to match.” – Jeremiah O’Driscoll

O’Driscoll previously collaborated with Zemeckis as an apprentice and later assistant to Schmidt on five of the director’s features, Death Becomes Her, Forrest Gump, Contact, What Lies Beneath and Cast Away. He was still a first when Schmidt called O’Driscoll in May of 2002 and asked him to help Zemeckis and producer Steve Starkey create a Leica reel based on Zemeckis’ outline for The Polar Express. “The animators had estimated that it would take two years to produce a Leica reel of the entire movie,” O’Driscoll said. “I figured that if I used the effects capabilities of the Avid to their fullest, I could approximate a 91-minute story reel in just four months. After bringing on Orlando Duenas, we also cut a one-minute sequence of test material from the script to completion and Warners gave us the green light 16 weeks before the start of principal photography––or more accurately, principal capture.”

According to O’Driscoll, the show was divided into two stages, the first of which began with the reference video created at the performance capture shoot.

“The editor takes the reference video, with all the actors’ moves and reactions shot from every conceivable direction, and recreates a real time performance assembly,” he explains. However, complicating this process was the limiting 10-by-10-foot performance capture grid (called a mocap volume) and a maximum take length of 90 seconds. “For example,” O’Driscoll says, “If the conductor walks the entire length of the train car, he must pass through the grid at least three times so that the editor can match footsteps out of one grid and into the next.”

This was not a guesswork process. The editor has to track exactly when and where the characters enter and exit the mocap volume and match them into their virtual environment. “For example, he explains, “When characters are following each other down a hall and up some stairs as they exit one volume and enter another, you have to count the number of steps to the stairs, count the number of stairs, and ensure that right foot falls match right foot falls, all the while watching the actual performance of lines and actions.”

O’Driscoll often worked with as many as six video layers (not counting background extras), each of which was covered by ten or more reference cameras covering the action. “Since Hanks plays both the conductor and the hero boy, the simplest scene between the two of them would be made up of two video layers, and each layer had to be tailored to work with the other because scenes were not acted to playback,” he says. “As an editor, I constantly judged who was driving the scene at any given moment and fit the other performance to match.”

O’Driscoll discovered that one of the joys of the process was that many scenes were not locked in almost until film out.

Once the performance assembly was completed to Zemeckis’ specifications, it was turned over to SPI for the rough integration of the performances, which took about a month from the initial turnover. “Several weeks later, we would receive a sync check with what Bob dubbed the “Michelin Men” [rudimentary low-resolution place-holding characters in a mock-up of the environment], and after more editorial scrutiny, a Maya file was created for further image processing.”

It was not until the second stage of production that anything resembling camera work and coverage could be created. Again, O’Driscoll’s skills were required to drive The Polar Express a bit farther down the track. “At this stage, the facial integration had still not been done, so I cut scenes with the ‘Michelin Men’ shots occupying most of the screen with the reference actor heads floating around along the top of the screen. Bob would sit in the ‘wheels’ rig, creating and reviewing coverage with directors of photography Don Burgess and Robert Presley. He would then leave a list of shot requests, which our assistants would track. On an average day, I would receive about 15 shots. I needed a vivid imagination to judge a scene under those conditions.”

Much has also been said about “wheels,” which, simply put, is a mechanical pan-and-tilt rig attached to a virtual camera in the computer that operates the same way as a crane. “Wheels” controlled depths of field, camera angles, lens selection, backgrounds, camera movement and shot duration; in short, anything beyond the actual performance. “We used the ‘wheels’ system so that the camera moves would not feel keyframed, but more organic, as if an actual operator were behind the camera,” O’Driscoll says.

“During this phase, we did a ‘spraydown,’ which was our way of getting basic coverage on every scene in the movie, and we did this by giving the DP license to cover the scenes in a very rudimentary fashion, getting a master and some coverage,” O’Driscoll adds. “Bob simply didn’t have the time to address the entire movie at once early on, but SPI still needed to know what shots were going to be there. Every shot was later redone and personally directed by Bob, but he did all that finessing of shots and camera work after a version of the movie already existed. We knew we would never turn over any of these shots, but it enabled us to get the running time down at an early stage.”

The editor has to track exactly when and where the characters enter and exit the mocap volume and match them into their virtual environment.

After a “wheels” shot came back to edit, O’Driscoll and first assistant Alex Olivares would once again scrutinize every move of every character and lay back five or more accompanying video tracks against the “wheels” shot. With that subclip, O’Driscoll cut the movie.

Even once Zemeckis locked his cut, counts needed to be done on every video layer, another daunting process. “A ‘wheels’ operator or Maya artist may have slipped pieces of action or performance in a particular scene to satisfy a request from Bob,” the editor relates.

Trust and communication were constant factors as The Polar Express evolved. This was especially true of the creative relationship between Zemeckis and O’Driscoll. “Bob is a very collaborative director, and made my transition from assistant to editor an easy one,” Driscoll says. “He has a very distinct vocabulary in his storytelling, and a great ability to respond to edited scenes without any preconceptions. He also doesn’t care if a shot takes three days to execute. If it doesn’t further the storytelling, then it’s history.” His long relationship with Zemeckis came into play at all stages of the production. “Much of my time was spent educating others about why Bob directs as he does.”

O’Driscoll also worked very closely with senior visual effects supervisor Jerome Chen at SPI. “Jerome and I were always working to come up with the most creative ways of trimming money out of shots without harming their intent, as well as dealing with continuity issues. With 40 or more people working on one shot, you can easily lose track of the big picture.”

O’Driscoll compares the dawn of nonlinear production to a similar time, some 15 years ago, when nonlinear post first appeared on the scene. “When Avid and Lightworks first appeared, some people adapted, and others left the business because they didn’t want to click a mouse,” he recalls. “You hear a lot of editors complain now about how we have to do temp scores and quick and dirty effects. They believe it is a drawback to suddenly have to assume a bigger slice of what a movie is. But we are entering into something that is completely new, and that brings new responsibilities and great opportunities to impact production.”

“The editor takes the reference video, with all the actors’ moves and reactions shot from every conceivable direction, and recreates a real time performance assembly,” – Jeremiah O’Driscoll

For one thing, O’Driscoll says, editors never before had to function as script supervisors. “Because shots were being farmed out to 300 artists, and because jobs were being entrusted to computer people that didn’t understand how movies are made, I had to watch continuity extremely carefully,” he explains. “You just can’t expect people that haven’t been around an Avid for ten years to be able to open up a bin and know what the coverage was. Things like this will have to be worked out in the future, and more to our benefit.”

But then, says O’Driscoll, much of what is usually done during production became a part of post to such an extent that relationships constantly crossed boundaries. For example, he says, “If the camera landed on the Hero Boy and then he blinked, something that only I could see in the video reference, I would make a request to the DP that the camera land a beat sooner to help the cut.” In the end, anything that could help the cut was fine, because O’Driscoll only was allowed a two-frame handle at the head and the tail on any given shot.

O’Driscoll discovered that one of the joys of the process was that many scenes were not locked in almost until film out, and unlike a traditional effects film, there was room in certain sequences to finesse some of the performances. “For example, in the scene near the end where Santa’s sleigh is taking off, the reaction shot of the Hero Boy and Hero Girl was taken from a totally different scene,” he says. “Sometimes it was a matter of torq’ing up a performance to get a little something extra that was different from what we’d been looking at through the entire movie.”

O’Driscoll’s skills were required to drive The Polar Express a bit farther down the track.

By far, says O’Driscoll, the biggest challenge on The Polar Express was the fact that Zemeckis was unable to see his film from start to finish for a full year after wrapping the performance capture shoot, because so many decisions had to be made before it could be viewed in its entirety. “We had to trust our intuition, and the visual effects supervisors, that it would all work out in the end,” he says.

In the end, Zemeckis came to love the process, because, as O’Driscoll explains, it freed the director from having to deal with both the performance and the cinematic aspects of the film at the same time. “One of the most unique new ideas about this is that once Bob was satisfied with the performances, he could attend to the cinematic aspects of the show in the comfort of an office full of layout artists,” he explains. “Bob would sit with me and review a scene and arrive at some inspiration for a new shot or camera move, then walk across the hall and sit with a layout artist for ten minutes making the shot. And I could cut it into the scene ten minutes after that.”

O’Driscoll continues: “In part because of what Orlando and I were able to create, Bob could work with this film the way he works with conventionally shot features. He wanted to keep The Polar Express as much like a real movie as possible and not go beyond existing cinematic vocabulary. ‘The good news is we can do anything, and the bad news is…we can do anything,’ he liked to say.”