by Michael Kunkes • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

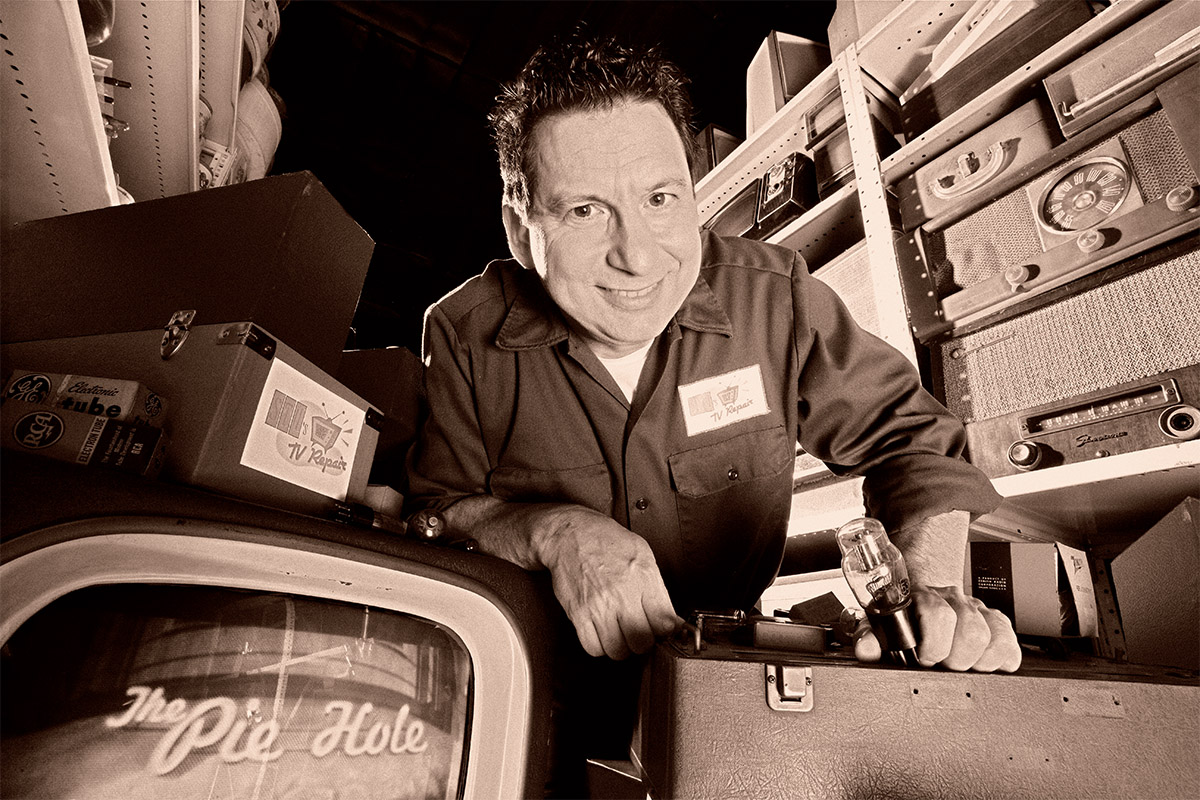

To hear Stuart Bass, ACE, talk about television editing, one might think he has an insouciant attitude towards his craft. “Editing comedy is a specific talent…it’s just difficult to say what that talent is,” he says glibly. According to his website, www.filmbutcher.com, he has written or has been a contributor to such books as How to Get Ahead in Hollywood Without Any Talent and Make Sure the Below-the-Line People Stay There. Also on the site, he extols a digital workflow of “dailies + lunch + paycheck = compelling cut of show,” maintains that his upbringing on a Wisconsin farm taught him to make splices with bailing wire and twine, and longs for the days when studio employees had to dodge Moviolas heaved from editing room windows by irate producers and directors.

Despite his poking good-natured fun at the industry — and himself (his e-mail moniker is TV Repairman) — Bass has a 27-year editing career that defies the popular notion of television as a toil-and-spin creative wasteland. Beginning with his work on the groundbreaking mid-1980s series The Wonder Years and continuing on shows such as Parker Lewis Can’t Lose, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Pushing Daisies, Arrested Development, Barber-shop and The Office, Bass has helped define the shape of the modern single-camera television comedy, removing the laugh track, adding the fourth wall and bringing to the small screen a synthesis of feature film and experimental cinematic ideas about writing, production and, of course, editing.

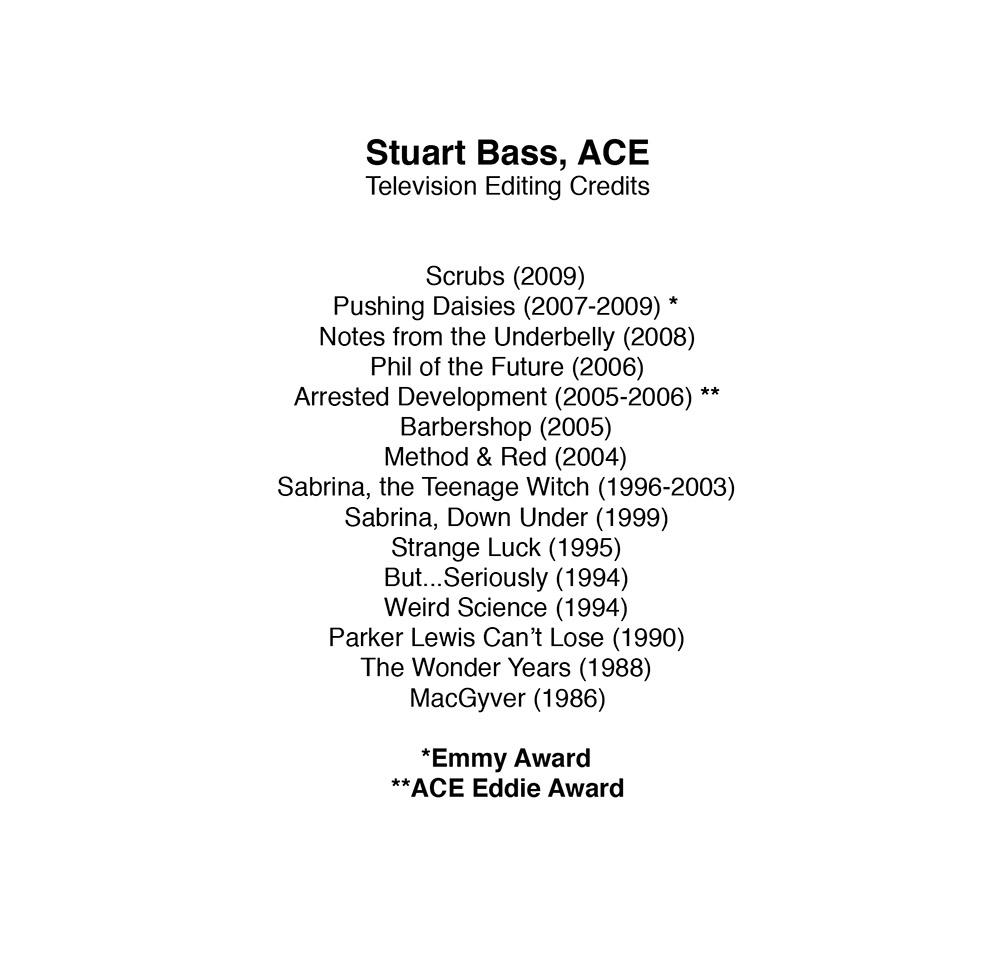

Just a year after winning an Emmy for his work on the pilot of the ill-fated but critically praised Pushing Daisies, Bass received a fourth Emmy nomination in 2009 for Outstanding Picture Editing for a Comedy Series, for the “Two Weeks” episode of The Office. He also won a 2006 ACE Eddie Award for his editing on Arrested Development. CineMontage spoke at length with Bass, who is currently an editor on the new season of ABC’s Scrubs.

CineMontage: Who are some of your cinematic influences and how have you applied that to comedy editing?

Stuart Bass: I am a huge Luis Buñuel fan because of the way he deals with time. He took film to a different level than just telling a linear story that begins on day one and ends on day ten. He made films that were dreams. I was also very influenced by the Germans like Douglas Sirk, Fritz Lang and Anthony Mann, as well as by underground independent filmmakers such as George Kuchar, and the subjective films of people like Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage and others.

The Coen Brothers and Woody Allen are big influences on my comic cutting rhythms. I remember taking a lot of ideas from Mike Nichols’ Carnal Knowledge and The Graduate when I started working on The Wonder Years, which I worked on for four years. Most recently, I have been inspired by editorial ideas from films like Amélie by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz and documentaries like The Staircase.

CM: How influential was The Wonder Years?

SB: The Wonder Years was the first real “dramedy,” where people were confronted with very real life and death situations. In terms of its editorial style, it developed a structure that was the opposite of jokes — there would be a setup, and then, instead of a punchline, there would be a tragic event. It wasn’t a pure comedy; it had moments where characters would be confronted with existential dilemma.

CM: You were recently nominated for an Emmy Award for an episode of The Office. What makes it a unique show to edit?

SB: As editors, we are constrained by the footage we are given. You can play with pace and performance, but ultimately, you will not be able to make drastic changes in tone. The Office has a great range of material. There’s usually about 18-22 hours of footage shot for each episode, so there are not only many scenes, but many takes of each scene. It can be frantic or slapstick, or depressing and introspective — all within the same episode.

“Two Weeks,” my Emmy-nominated episode, had long uncomfortable moments, sight gags, ambiguous dialogue and quiet moments, much like the British version of the show. With that kind of off-the-chart dynamic range, you could take a show and make it a dour, slow-paced Antonioni movie on one end, or pace it up, get more jokes in and turn it into a Commedia dell’Arte farce. Editorially, we could take it almost anywhere, and that’s what made it really fun to cut. I discussed this issue with Ricky Gervais [original creator of The Office for BBC], who really enjoys the pacing of the American version.

CM: How does your editorial style differ on a show like The Office, which has almost no music or visual effects, from shows like Arrested Development or Pushing Daisies, which are much more fleshed out sonically and visually?

SB: On The Office, we have the feeling and flow of a documentary, because the talking heads and the hand-held shots have to follow real-time film conventions. If you changed angles, you cut on the angle change and you didn’t do jump cuts or dissolves. Interestingly, Arrested Development had the same documentary approach, but with a lot fewer traditional rules. We came up with crazy graphics to cut to, played with time in different ways and used split screens. When I tried to do these things on The Office I was called out by executive producer Greg Daniels, though in later episodes, I did manage to stretch his rules. But ultimately, on Arrested, we didn’t care about conventions, as long as it was funny. I approached Pushing Daisies in a much more cinematic way, ignoring coverage and letting beautiful masters tell the story. Not cutting became cutting. It was Zen-like.

CM: Some of these shows reflect a guerilla-filmmaking sensibility.

SB: Without a doubt. In an episode of Arrested Development, the David Cross character has a scene where he’s being helped out of a wheelchair, and we had no coverage, only many takes of a master, and there was just no way to make it work. In the end, I just took the funniest pieces of him falling off the chair and jump cut them together. And if you think about it, it makes no sense because it’s the same take over and over again. But it worked. Serendipity.

CM: You’re currently working on Scrubs, which is going through a lot of changes.

SB: The show has moved to ABC and is introducing new and younger characters in a teaching hospital environment. So far, I like what I am seeing; it’s a lot like the Scrubs I remember from nine years ago.

CM: What is the director-editor relationship like in television comedy?

SB: Michael Dinner once likened TV directors to traffic cops — they are, for the most part, hired hands who change every week. Like the editors, they are trying to realize the executive producers/writers’ vision. Veteran directors will make wonderful dailies where the shots flow together organically. They may suggest a few adjustments to my cut, see something I missed, or even enjoy my take on something they didn’t expect.

Then the next week, I’ll be cursing and struggling with a rookie director’s footage, and invariably he will come into the editing room for long painful days of fixing his mistakes, and then, predictably, go back to the way I had it. As Walter Brennan said on The Real McCoys, “No brag, just fact.” I think I suffer from director-bipolar disease; my happiness is very dependent on the director of the day.

I have really enjoyed working with Barry Sonnenfeld, who first became known for his DP work with the Coen Brothers and has gone on to direct Get Shorty, Men in Black and others. In TV, as an executive producer and director, he collaborates on all aspects of writing and production. He gives everyone around him terrific support, respect and creative freedom. I’ve been with him on three shows — Notes from the Underbelly, Suburban Shootout and Pushing Daisies — and because our senses of humor are in sync, and we have similar tastes in music and comedy, we are able to elevate the footage beyond the original script.

CM: How do you view the role of the editor in a comedy show?

CM: How do you view the role of the editor in a comedy show?

SB: I generally work with the executive producers/writers to keep the tone of the show consistent, even as the directors change weekly. Many of them are super-humans: Bryan Fuller, John Ridley, Mitch Hurwitz, Nell Scovell, Greg Daniels, Bill Lawrence. They balance writing, producing, network relations, promotion, management and budgets, and are still able to maintain a focused creative vision. My number-one mission is to interpret that vision. In turn, they recognize the importance of editors and what we bring to the table. When schedules get tough and production is compromised, we are in the trenches together fighting the battles. I’ve been lucky enough to work with the nicest and most generous of these folk.

CM: How much of an actor’s performance is created in the editing room?

SB: On shows like The Office, or on the pilot for Pushing Daisies, there is enough time for rehearsals. Editing performance becomes an exercise in nuance and subtext. However, television acting is often also the world of the 11-page shooting day with no preparation, and that’s when performance becomes editing. It’s all about stealing reactions, covering mistakes, revoicing intonations, pulling up pauses and creating moments.

Every day, I thank Stan Tischler, whom I assisted many years ago and who got me my first editing credit. I sat behind him for two years on After MASH and got a PhD in shaping comic performance. Stan alone didn’t make this stuff up; I owe a debt of gratitude to a century-old collective knowledge base of Hollywood editors.

CM: How much do you work with music and sound effects?

SB: Though we still use music editors and sound editors, producers today expect to see things as fully realized as possible, with sound effects, opticals and music cut in, as opposed to doing what used to be called a “rough cut.” The importance varies from show to show. On Parker Lewis Can’t Lose, action was timed to the sound effects, so they became a really important element in the first cut. The Pushing Daisies pilot was wall-to-wall music, and we had a big job filling temp music until the composer took it over many weeks later. Typically, once a show is done, we pull OMF files, and all my music and sound effects choices end up on the dub stage; hopefully, the sound crew enhances these rough tracks and adds more depth.

CM: What’s the difference between a sitcom and a comedy?

SB: In a sitcom, someone ends up on the balcony of his apartment in the middle of the night in his fluffy slippers and can’t get back into the house. In a comedy, someone could die at the end. Sometimes the joke is through a character’s unique view of a creepy world, but you are not making puns and jokes and insults, which is the stock in trade of the sitcom.

CM: Where do you see television comedy going?

SB: We’re in a period now with very few multi-camera sitcoms. They still look the same today as they did in 1980: four cameras, three walls, two characters and a couch. There are a few very good ones, such as Two and a Half Men and How I Met Your Mother. They are just not very popular right now but will be again. They’re just dumb fun and have done very well over the years, simply because they are cheap to make and the studios are cutting back.

The corporate mindset tends to shun risk, so I think we’ll be seeing a lot of less risky television. Every season, some terrific innovative pilots are made, but almost none of them are picked up. There was a time when a few great shows could garner Emmys and stay on the air without having great ratings, but not in this climate. Networks are not going to sell advertising where they have to look for an audience. Unfortunately, it’s part of the general dumbing down of television.

CM: Dumbing down?

SB: When I talk about dumbing down, I don’t mean that in a bad way. The first sitcoms were cavemen sitting around campfires making poop jokes. Then pretentious, sophisticated cavemen like me secretly laughed with them — and then told their cohorts it was vulgar. Anyway, if we smartened up TV, the advertisers would jump to someplace like YouTube.

CM: Was the transition to non-linear editing difficult for you?

SB: Not for me. I started working on non-linear videotape systems back in 1983 as an assistant on After MASH, when CBS and Sony introduced their experimental system. I also cut shows on the Montage, Touchvision, Ediflex and others. My first show on the Avid was in 1994 — a documentary for Rob Reiner called But…Seriously, which earned an editing Emmy nomination.

It seemed like we were learning a new machine every few months, and Avid was simply one more machine on the continuum. Right now, I am cutting Scrubs on Final Cut Pro. Despite the technology, editing still seems to be about character, story and performance.

CM: What is your role with the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences?

SB: I am in my third year as a Governor of the Academy, and I regard myself as a spy for ACE and the Editors Guild. It’s been a great way to give back to the industry and guard against the movement to perceive picture editors as workstation clones.

CM: Have you ever gone after feature work?

SB: Yes, and I’ve given up. Feature people don’t want to hire a “TV guy.” That’s just the reality of it. Just don’t ask me to do any reality shows!