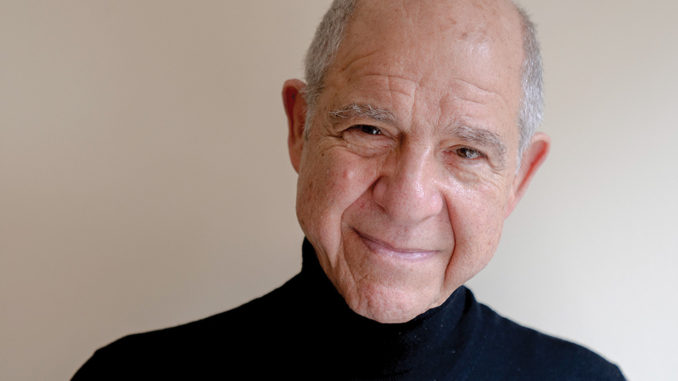

by Peter Tonguette • portraits by Sarah Shatz

When Lee Dichter, CAS, was informed that he would receive the Motion Picture Editors Guild’s 2018 Fellowship and Service Award, it did not take long for the veteran sound re-recording mixer to accept. In fact, it took the equivalent of about “six frames of film” for him to reply, he says.

“When I was notified by [Guild president] Alan Heim about the selection for the award, I was flabbergasted,” Dichter adds. “It was a spontaneous reaction that I accepted, and it definitely feels like a lifetime achievement, in a way.”

The cacophony of credits Dichter has amassed over a five-decade career — including multi-film collaborations with directors Woody Allen, Robert Altman, Nora Ephron, Sidney Lumet and Mike Nichols — more than qualifies him for celebration. Yet the award’s emphasis on other attributes, including a concern for labor issues, is what moves him most.

“In 1943, my father, Murray Dichter, was a charter member of the New York Motion Picture Editors Guild, IATSE Local 771, which was formed several years after the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors launched in Los Angeles in 1937, and he became a member of Local 52, the Motion Picture Studio Mechanics, in 1959,” Dichter says. The SMPFE became IATSE Local 776, the West Coast’s guild for film editors, in 1944.

Yet Dichter — who was born in 1944 in Brooklyn, New York — has roots in show business that stretch back even further. In the 1920s, his maternal grandfather Joseph Seiden, who was the son of a vaudeville veteran, started producing and directing films with Yiddish themes. “He had the idea of making films of the Yiddish plays that were on the Lower East Side so more people could see them,” Dichter relates. “Of course, it was all silent film at that time, but he needed my father to make the transition to sound.”

After studying at Cooper Union, Murray Dichter became an electrical engineer and established a radio repair shop that specialized in automobile radios. “These were tube radios, so they constantly were blowing out going over the potholes and everything,” Dichter comments. “The radios needed constant repair.” One of Murray Dichter’s customers was Seiden, with whom he began working in the early 1930s when the filmmaker switched to sound films. In 1936, Murray Dichter married Seiden’s eldest daughter, Natalie.

“My father learned everything about film recording techniques, and he applied it to my grandfather’s work,” Dichter observes. “Eventually, he left my grandfather because they were two strong-willed men. He left and opened up a studio, Dichter Sound Studios, which focused on TV commercials.”

In those days, advertisers sought to control both the picture and sound of their spots. “They wanted to have it consistent so the picture would look beautiful and sound great,” Dichter says. “He had set up the studio, mainly for TV commercials, in a building that he had bought on 54th Street between 9th and 10th Avenues. It was an old church, in fact.” In the five-story building, shooting stages occupied the second and third floors, sound recording took place on the ground floor, and editing was done in the basement. “It was the first large editorial service in the city,” Dichter explains. “The commercials were shot upstairs and then cut downstairs.”

On weekends, young Lee began assisting his father, learning how to thread dubbing machines and observing him putting the finishing touches on episodes of the CBS program Eye on New York and other projects in the late 1950s. “I really loved being there,” Dichter says, “and he exposed me to all sides of it.”

Dichter spent a single year at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “I was not a good student as far as test-taking and studying,” he remembers. “Most of my knowledge was intuitive. I was very good in math, very good in sciences, but I didn’t do well in the languages and other areas.” Asked when he decided to leave college, he replies succinctly: “Well, they decided.”

Following in the Family Business

Back home in New York, he joined the US Coast Guard Reserves before going to work for Dichter Sound Studios full-time in 1964. “I wasn’t sure what I was going to do,” Dichter comments. “My dad was doing the mixing on commercials. I was still just working in the back room, doing copies and transfers, and setting up the machines.” On the advice of his older brother Mark, who had also worked at the studio before striking out as a location sound recordist, Dichter decided to branch out — as an assistant sound recordist (and actor) on Joseph W. Sarno’s Flesh and Lace (1965) and as an assistant editor on Sarno’s Moonlighting Wives (1966). Neither job took.

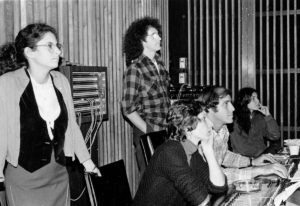

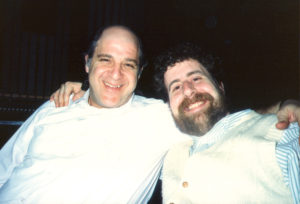

Photo by Murray Dichter

“I didn’t like it at all when I was on location,” Dichter concedes. “I’d be sitting there for an hour while they’re setting up the shot, the lighting and the whole thing. I ended up reading the paper half the day. I’m more of an active guy. So I asked Dad, ‘Could I come back into the studio?’ It wasn’t even a question; ‘Absolutely.’”

In 1966, on the heels of financial challenges at the company, Dichter Sound Studios joined forces with Photo-Mag on East 44th Street. The following year, Dichter, like his father had, joined Local 52, which had the re-recording mixing jurisdiction in New York.

It was at Photo-Mag that Dichter began to mix for the first time. “I learned more and more about what sound actually was and how to deal with the intricacies and different sounds coming into me,” he says. Dichter worked on TV commercials — straightforward jobs that offered valuable experience. “I started with narration, music and one dialogue track,” he explains. “My dad wouldn’t give me anything that was complicated since I was just learning. But there came a time when the clients started asking for me. Once I worked with somebody, they wanted to come back.”

During the late 1960s and early ’70s, TV commercials remained the company’s bread and butter, but Dichter started to work on low-budget documentaries and feature films, including Peter Davis’ The Selling of the Pentagon (1971) for CBS and a series of low-budget films for director Don Schain. “All through this time, I would do one movie, but that was it,” he comments. “I would be doing 11 months of commercials, and occasionally I would get a film.”

Dichter’s desire to move on from advertisements and expand into film caused a bit of tension within the family business. “My dad was not pushing for me to do feature films at all,” Dichter recalls. “If I did one feature, it would take me two or three weeks. With commercials, I could do eight a day, so you had a much larger client base, which made them happy.” Yet Dichter savored the creative challenge of working on features. “That’s where I really felt that I could contribute more to the overall project,” he explains. “You can only do so much in a 30-second or 60-second commercial. Every word has got to be heard. Everything has to be out in front. You can’t really have the subtleties.”

Photo by Ivan Henry

Indeed, Dichter was drawn to non-fiction films due to the content of the material, as well as the often dodgy location sound he was tasked with mixing. “Actually, documentary was my first love because that was taking sound and making it sing; many of them didn’t have good sound,” he says. “I was able to really go for it as far as equalization was concerned. I could really dig in and learn how to grab a track and work with the dialogue to bring it alive.” Dichter’s documentary credits during these years include such acclaimed efforts as the Maysles brothers’ Grey Gardens (1975), Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, USA (1976) and George Butler and Robert Fiore’s Pumping Iron (1977).

Into the 1980s and ’90s, even as Dichter’s career in features had taken off, the re-recording mixer continued to keep a hand in docs, mixing Kopple’s 1990 film American Dream, which went on to a win an Academy Award. The film, which chronicles a strike that unfolded the previous decade at a Minnesota meatpacking facility, directly concerns the labor movement. “There was this one little sequence that I’ll never forget,” Dichter stresses. “There was somebody talking upfront who was muffled, and someone right behind who was screaming on camera, and I had to get both of them.” Yet if equalization was added to the scene, the screaming would be rendered even sharper, so the mixer had to get creative. “By de-essing the loud one, I was able to bring the other one up,” he explains, referring to the process by which “ess” sounds are diminished on the soundtrack.

Dichter’s generosity of spirit — another hallmark of the Fellowship and Service Award — is evidenced in his passion for one of his most notable documentaries, Rob Epstein’s The Times of Harvey Milk (1984), which takes as its subject Harvey Milk, an openly gay politician in San Francisco who was murdered in 1978. A store run by Milk’s family was located in Dichter’s boyhood town of Woodmere, New York. “They sold clothing and sneakers and things,” Dichter remembers. “My mother used to bring me in frequently as I was growing out of my sneakers at a rapid pace. The Milks lived around the corner from us, and I would walk past their home daily. Working on the actual film itself was very moving.”

The mixer had the opportunity to leave Photo-Mag for Trans/Audio — the company created by brothers John F. and Richard J. Vorisek that had since merged with Todd-AO — about six years earlier, but his father discouraged him from doing so. “I said, ‘Dad, I was contacted by Trans/Audio. They want to have a meeting with me. What should I do?’” Dichter recalls. “He said, ‘As a businessman, I have to tell you to go. As a father, I have to tell you not to go.’ My father drew the line. I made the decision to stay because I couldn’t live with breaking up the family.”

Landing at Sound One

Photo by Susan Lazarus

In 1980, however, Dichter’s younger brother Bobby unexpectedly died, leaving the family, particularly his father, despondent. “My dad also taught him how to mix,” Dichter says. “From that point on, Dad was crushed and didn’t come to work much. After my father was diagnosed with inoperable cancer, his business partner tried to take control of the company, making it untenable for me to continue to work there.” Star 80 — Bob Fosse’s 1983 film about the murder of Playboy model and burgeoning film actress Dorothy Stratten — had been booked to mix at Photo-Mag but moved with Dichter to Sound One that year. “It was during the second week of the mix that my father died,” he says. “It was a very dramatic and traumatic transition.”

After Dichter settled into his new job, however, he found that Sound One was the perfect landing spot. “They had about 35 rooms of picture and sound editing for features and documentaries,” Dichter says. “They did Foley recording. They did ADR recording. We had none of that over at Photo-Mag because we weren’t set up for it.”

What’s more, the re-recording mixer was able to hit the ground running with a client list he took with him from Photo-Mag. Among his 24 credits in 1984-1985, for example, were films for directors Francis Ford Coppola (The Cotton Club), Sidney Lumet (Garbo Talks), Arthur Penn (Target) and Jerry Schatzberg (Misunderstood). “I just knew I was in the thick of it,” Dichter comments. “Sometimes when you’re mixing a film the hours can be crazy, but it was always very exciting to be working with some top directors and editors in the business.”

Photo by Susan Lazarus

One significant relationship almost began at Photo-Mag but flourished at Sound One: Dichter’s 31-film collaboration with Woody Allen. While Dichter was still at Photo-Mag, Allen’s longtime editor, Susan E. Morse, ACE, persuaded the director to switch from Magno Sound to work with Dichter. “A week before the mix of Zelig [1983], Susan came in to do a temp mix,” Dichter recalls. “She ran it for Woody and he said, ‘It’s not working. We have to re-cut the picture.’ It would be ready to mix two months later, but I was already booked on something else.”

Four years later, Morse again asked Allen to collaborate with Dichter on Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). This go-around, however, the timing worked out and the mixer embarked on a working relationship that endured for more than three decades and earned him a BAFTA Film Award nomination for Best Sound for his work on Allen’s Radio Days (1987). “I attribute it all to Sandy Morse,” says Dichter, who discovered that his preference for natural-sounding dialogue meshed with Allen’s.

“As far as mixing dialogue, the whole key to me is to try to make it sound as if you’re part of the conversation,” Dichter continues. “We’re POV of the camera, and you want to feel like it’s real dialogue, real sound that’s full-frequency and not pinched, over-equalized and over-filtered.”

He would eventually preside over Allen’s reluctant transition from mono to stereo soundtracks. Dichter himself had first mixed in stereo on Stan Lathan’s Beat Street (1984). “Woody liked mono,” he says. “It’s what he grew up with. He equated the big stereo stuff with the Hollywood sound, and he didn’t like that.” Dichter’s initial attempt came on the musical comedy Everyone Says I Love You (1996), but when the mixer screened reel one for the director in a stereo mix, the reaction was not what was hoped for.

“Woody asked, ‘What’s that?’” Dichter remembers. “I said, ‘Well, the opening music; it’s nice.’ He said, ‘It’s too big, it’s too fat, it’s too wide, it’s too…everything. I want to bring it more to the middle of the screen.’” Allen was only satisfied when Dichter had moved the sound from full stereo to mono: “He said, ‘That’s it.’ I said, ‘It’s right down the middle.’ He said, ‘It’s perfect.’”

Allen finally made the jump to stereo on Cassandra’s Dream (2007); composer Philip Glass’ original score for the film would not fold into mono because of phase cancellation, in which sounds are lessened or lost in a mix. Nevertheless, Dichter still had to mind his Ps and Qs. “We didn’t use the word ‘stereo’ because that was too dangerous,” he jokes. “We used the word ‘spread’ — ‘spread the music a little.’” The mix mainly used the center channel, a little left, a little right, but only the tiniest hint of surrounds.

Mixing in New York for his entire career, Dichter came to feel that he worked on a certain kind of film, even though each project — and each director — was distinct. “We’re telling stories in New York,” Dichter observes. “Coming from theatre, the storyline is important.” He points to Mike Nichols, with whom he worked on 13 films, including Working Girl (1988), The Birdcage (1996) and the HBO miniseries Angels in America (2003), for which Dichter shared a CAS Award from the Cinema Audio Society Award for Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television – Movies and Miniseries. “Mike did a movie, then did a play, did a movie, did a play,” Dichter comments. “He loved the process. A lot of directors just come in for the final mix, but he would be involved earlier.”

In between his work on A-list films, Dichter found time to take on more unusual projects. He mixed numerous documentaries for Ken Burns, including The Civil War miniseries (1990). “We had to make still pictures feel like live action by working with the soundtracks,” Dichter says. “They had the archival cannon sounds and musket sounds. That was a wonderful experience in bringing those shots alive.”

In 1992, the re-recording mixer also “collaborated” with Orson Welles; even though the master filmmaker died in 1985, Dichter mixed a restoration of his 1951 adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello. “It was very challenging because we were working with tracks from all over the place,” Dichter says. “He shot it over many years because he didn’t have the money. With the restoration, we put some new music over the dialogue, so we had to dip things in and out and go around and use all kinds of equipment to try to clean up the tracks.”

Labor-Intensive

Yet his years at Sound One were not limited to creative challenges. Equally significant, if not more so, was the part he played in organizing the non-union shop, which became a signatory to the IA contract in 1996. “I was union, and there were a few other union members there,” says Dichter, who also supported the rights of sound professionals across New York. “I was trying to at least get parity for the members — the young fellows who were coming in who were in the machine room. My drive was just to have equal pay across the board from different companies in the city doing the same work.”

In 1999, Dichter became a proud member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild, IATSE Local 700 (formed when Locals 771 and 776 merged in 1998) after Local 52 ceded its re-recording jurisdiction in New York to the national Editors Guild.

With the same spirit of collegiality that he demonstrated in the organization of Sound One, Dichter also strove to provide guidance to re-recording mixers as they rose through the ranks. “Young mixers have sat next to me many times and they want to know: ‘Why am I doing this? Why am I doing that?’” he comments. “Michael Barry had a background in music mixing, and he was making a transition into film mixing, which means learning the dialogue. He sat with me for weeks while I was working on a film. It takes a long time to really become a good mixer.”

Dichter feels it is imperative to pass along knowledge from one generation of mixers to the next — especially important in light of his decision to retire last year. After mixing Allen’s most recent film, Wonder Wheel (2017), he opted to call it a career. “The last three or four years, my hearing has been slightly decreasing,” Dichter explains. “I did not want to compromise the soundtrack. I wanted to end my career on a high.”

Yet, in a sense, Dichter’s career has been one continuous high point. “My wife, Sophie, says to me, ‘You don’t realize how lucky you are,’” the mixer reflects. “I say, ‘What do you mean?’ She says, ‘You never had to sell. You never had to go out and try to get a movie.’ And it’s true; I never made one phone call. You build up relationships with editors and directors, and they come back.”