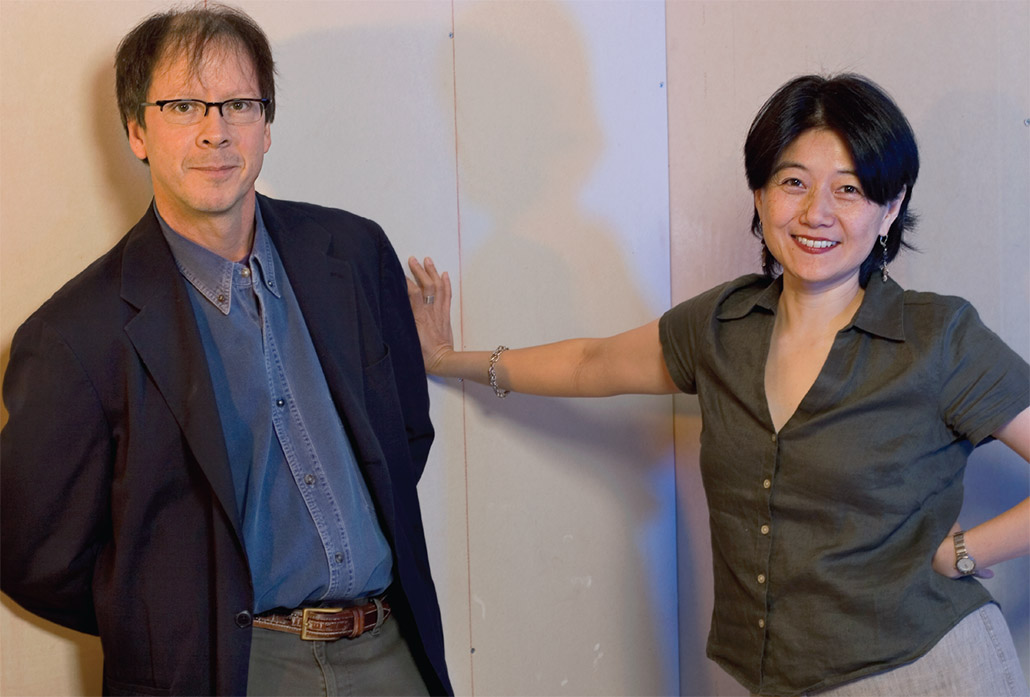

by Kevin Lewis • photos by Kfir Ziv

Li-Shin Yu has become an expert on the American experience. The editor’s long association with writer/director Ric Burns has certainly contributed to her education. Many of the documentaries she has edited for Burns and his Steeplechase Films have been presented by PBS, including, appropriately enough, as part of its series The American Experience. Two new documentaries written and directed by Burns and edited by Yu will be broadcast this year on PBS: Eugene O’Neill: A Documentary Film will be an American Experience presentation in April and Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film (co-edited by Juliana Parroni) will be an American Masters broadcast in the summer months. Burns has always credited Yu for her invaluable contribution to his films, and she won an Emmy Award for editing his New York: A Documentary Film (1999).

Yu immigrated to the United States from Taiwan when she was five years old. After graduating from Pomona College in California, she moved to New York in the early 1980s. “I was completely smitten by New York—by the place, by the energy, by what seemed to be available for me here,” she says. Graduating with a degree in art and planning on remaining a painter, she was drawn to the visual possibilities of motion pictures as a moving canvas of color and composition. “The word for movies in Chinese translates to ‘electric shadows,’ she points out.

Because she enrolled in a course on filmmaking at Columbia University, Yu was able to meet kindred spirits at both Columbia and New York University, including NYU graduate film student Frank Prinzi, (now a director and cinematographer) who knew Jim Jarmusch and Spike Lee and served as camera operator on both the former’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984) and the latter’s She’s Gotta Have It (1986). Through the connection, Yu was hired as a camera operator on both films as well. The two films became touchstones for much of New York-based independent filmmaking scene and today are classics. “I really had no idea about how big they were both going to become,” she confesses. “But I think we all had a sense that we were working on something special.”

Independent film interested her more than studio-based production, and her career has continued on that course in both feature film and documentaries. Early on in her career, Yu was not sure if she wanted to go into camera work or editing––so she did both. But she soon realized that she had to choose between the two technical skills. “I decided editing was more suited to my temperament,” she says, and felt that it was “closer to the creative process.”

According to Yu, editing a documentary is more satisfying because it offers more of a collaborative experience than feature film work. Around 1984, when she began editing documentaries and features, she joined the Editors Guild because of encouragement from colleagues. “Being a Guild member has provided and guaranteed basic rights in wages, health benefits and overtime protection—standards, which all working Americans should have,” she explains.

Since 1994, she has worked with Burns on such documentaries as The Way West (1995), New York: A Documentary Film and Ansel Adams: A Documentary Film (2002), as well as the two upcoming films. Michael Levine, the editor for whom Yu had worked, initially recommended her to Burns, beginning what has become a very close and mutually beneficial working relationship. “Ric’s commitment to excellence, his passion to dig deep into his subjects—whether bright or dark—and his intelligence and intellectual curiosity expand my own knowledge and understanding of not only the subject of the film, but of any other subjects about life, art, politics and the state of our city and country that inevitably come up when you work side-by-side with someone over the course of making a film.”

Yu explains that the scripts written by Burns are “very scripted and idea-driven,” so historical footage that fits the narrative—whether it is narration or talking head interviews—determines the selection process. Sometimes footage is used as a metaphor for the narration, Yu explains, as in her work on the New York series.

For the “Cosmopolis 1919-1931” episode of the eight-part New York: A Documentary History, she won an Emmy (shared with co-editor Nina Schulman) for Outstanding Achievement in Non-Fiction Programming—Picture Editing. Working on this episode was fascinating for Yu because the jazz age in Manhattan was, in her words, “wacky and daredevil; the sky’s the limit with everyone pushing the limit. And so the footage clearly spoke to that.” The actuality footage was not strictly scripted but used metaphorically to complement the narration and music––and “to express an age,” she says.

To illustrate this point, Yu recalls footage of elephants in the street, with kids running by. “Everyone was just exuberant—but it was not talking about the circus coming to town,” she says. “In some way it helped us focus the narrative.” The metaphor of the circus image reinforces a narrative idea about the frenzied Roaring Twenties.

“Films take on the rhythm of the music. It’s all interwoven,” – Li-Shin Yu

Surprisingly, the torturous decision-making involved in isolating the moment in historical footage and cutting it from its context doesn’t frustrate Yu. “For me, it doesn’t seem hard because the narrative tells you where something is no longer needed.” Her background as a painter is invaluable because the principles of painting are rooted in eliminating what detracts from the whole—the accept and reject method.

The editing can be brutal in any case. Because almost every aspect of Andy Warhol’s life was recorded on film, in performance art style, the voluminous footage available was overwhelming for a three-hour film, and therefore employs two editors. On the other hand, historical footage of the publicity-shy Eugene O’Neill does not exist except for brief home movies of the playwright and his family. To augment O’Neill’s themes and life, Burns directed scenes from his plays (featuring esteemed actors such as Christopher Plummer), which have to be edited to fit the roughly 115-minute American Experience time slot. The first assembly cut of the O’Neill documentary was five hours.

Yu is very comfortable working either solo or in tandem with a co-editor. Earlier in her career, before she met Burns, she was associate editor on the Jonathan Demme documentary Cousin Bobby (1990). “Being the associate editor, I didn’t have that much one-on-one contact with him, but he was very open.” Understanding the story thoroughly in discussions with the director is essential in a collaborative process, Yu says. “It’s a mutual understanding of our goals. Making a film is so hard. If you’re in an adversarial relationship, there’s no collaboration.”

Burns agrees. “The script will go through many drafts before it gets into the editing room,” he says. “Once it’s there, Li-Shin will cut it. By that time, she’ll know the visual material really, really well and she’ll pull it together. So, at that point, we’ll sit down and look at the assembly and it will be filled with possibilities and problems and we’ll tackle these together.

“Being a Guild member has provided and guaranteed basic rights in wages, health benefits and overtime protection—standards, which all working Americans should have,” – Li-Shin Yu

“Sometimes the problems that have to be addressed require extensive rewriting,” he continues. “Often it requires some difficult rewriting. But as Li-Shin was saying, from the assembly on, we spend more and more time together in the cutting room—as much for me to avail myself of what she’s doing as for her to avail herself of what I’m doing.”

In a reversal of the usual process, Yu edits to the soundtrack music, which is composed in the early days of production after meetings with Burns and the composer [see accompanying sidebar]. “Films take on the rhythm of the music. It’s all interwoven,” she says.

Despite the fact that Steeplechase Films is one of the most successful producing companies with ready backing for its projects, the company, which specializes in historical documentaries, has moved slowly into new technology. The films are shot on Super-16mm and converted to digital format, but cut on the Avid using Media Composer 7.2.

“I’m glad that we waited a very long time to begin cutting on Avid,” Burns says. “We cut half of the New York series on a Steenbeck. I’m also very glad that we switched.” But he adds, “The best thing you could do for someone who is coming up as an editor is to make them cut a film on film. Then, once they really cut on film, give them an Avid or Final Cut Pro, or whatever it turns out to be. Because at that point, they’ll understand.”

Though the Taiwan film industry has produced world-class films, Yu, who cut a film in her native country years ago, has no plans at this time to become part of it. Her parents still live in Taiwan and she admits to strong connections; she even has edited three documentaries on the Chinese and the Chinese-American experience: Between Two Worlds: Becoming American Chinese in America [Episode Two] (2000), Journey to the West: Chinese Medicine Today (2001) and Sparrow Village (2002), the latter about a young girl in rural China. “I think I’m too much of a New Yorker, perhaps,” she concludes.