by Laura Almo • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

The 19th annual Invisible Art Visible Artists event with Academy award-nominated picture editors took place on Saturday morning, February 23 — Oscars Eve — at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. As in preceding years, the event drew a near-capacity crowd excited to hear the panelists converse about the art of editing in the annual “From Dailies to Nominations” panel presented by the American Cinema Editors (ACE), with support of the Editors Guild.

The morning began with a warm welcome from the American Cinematheque’s Margot Gerber, who then introduced ACE President and Guild Board member, Stephen Rivkin, ACE. Rivkin thanked all of the staff and volunteers at the Cinematheque and from ACE.

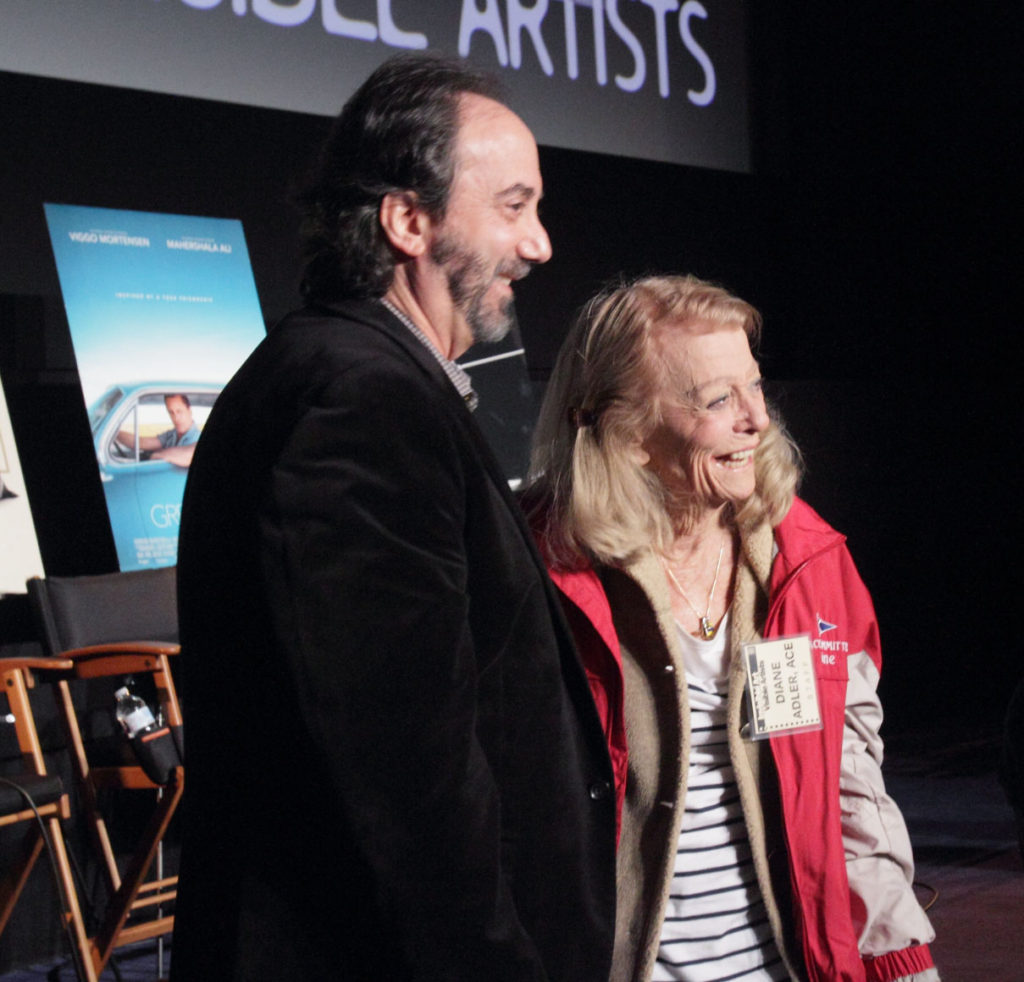

He then asked the audience to take a moment to recognize Diane Adler, ACE, who has been producing the IAVA event since its inception 19 years ago. “[Diane] has been at the heart and soul of ACE and the Editors Guild for decades [and] none of this would be possible if it weren’t for her guiding force,” he said. “She has helped us grow to what we are as an organization today.” Rivkin asked the audience to join him in a “thankful round of applause” and when Adler stood up, so too did the audience to a rousing standing ovation. He also thanked the sponsors of the event: Blackmagic Design, Adobe, the Editors Guild and NAB.

Before the panel got underway, Rivkin addressed the audience about the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ (AMPAS) erstwhile decision to “make some trims” for the 91st Oscars show. Earlier in the month, the Academy had announced it would present the awards for Film Editing, Cinematography, Makeup and Hair Styling, and Live Action Short during commercial breaks of the ceremony’s broadcast. A deluge of dissent from the industry urged the Academy to reconsider that decision, and AMPAS reversed its edict.

“The tremendous outpouring of protests on our behalf from prominent filmmakers, industry leaders and directors was astounding, and it really did confirm the undeniable truth that editing is one of the backbones of the filmmaking process…,” Rivkin said, then paused for applause and continued, “…and apparently it served our purpose in raising the awareness and perception of editing. So, we are very thankful that the Academy had the wisdom to back off on its decision, and all awards will be aired in their entirety tomorrow.”

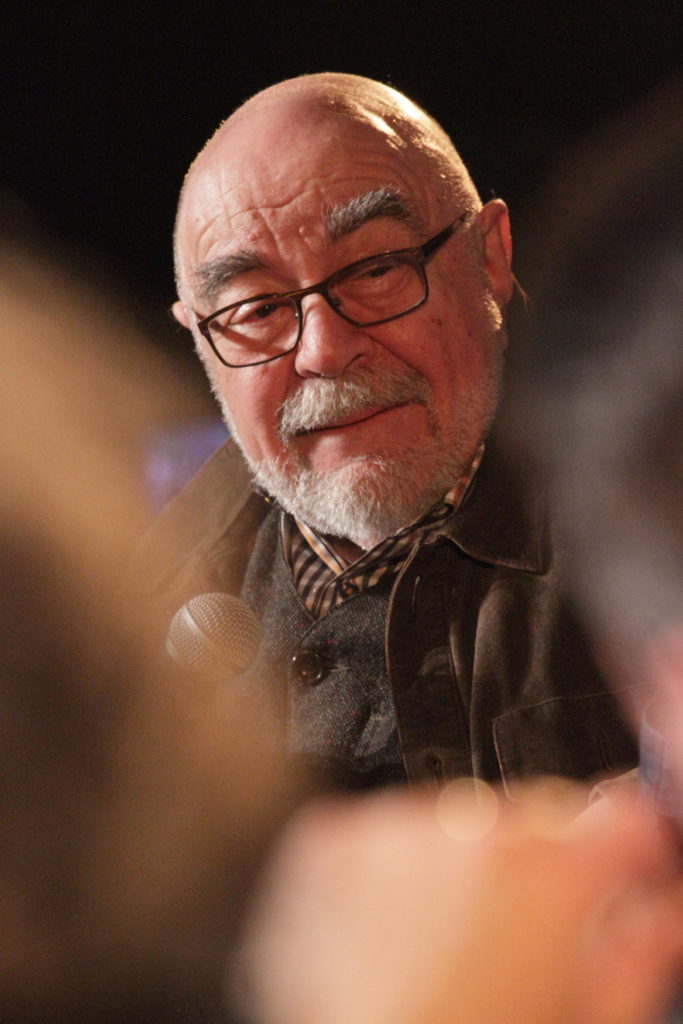

With that, he introduced moderator Alan Heim, ACE, President of the Editors Guild. Heim won an Academy Award for All That Jazz (1979) and was nominated for an Oscar for Network (1976). Following that, the five Oscar-nominated editors were introduced: Barry Alexander Brown (BlacKkKlansman), John Ottman, ACE (Bohemian Rhapsody), Yorgos Mavroposaridis, ACE (The Favourite), Patrick J. Don Vito (Green Book) and Hank Corwin, ACE (Vice).

Heim then took the reins, quipping that, “All of this would be included in the broadcast, were there to be a broadcast,” and then asked each of the editors to give a “concise history” of how he got started.

The English-born Brown started off the intros by divulging that he began in documentaries, but not as an editor, “Eventually I was cutting my own docs because I couldn’t afford an editor and my friends in the mid-1980s — we were all broke — Spike Lee, Mira Nair…they thought I could edit and so they hired me. And they hired me over and over and turned me into an editor.” He said he began his collaboration with Lee on She’s Gotta Have It (1986), for which he cut one scene. After that, he cut Lee’s School Daze (1988) To date, the editor has collaborated with director on over a dozen films.

A graduate of USC film school of Cinematic Arts, Ottman said, “I was one of those weird kids who made little films in my parents’ garage.” He kept on making movies all the way through USC, where he was interested in both editing and composing film scores. After USC, Ottman got some equipment together and started scoring friends’ student films, although filmmaking and editing became the priority. His credits include the Sundance Film Public Access (1993) and Superman Returns (2006), both of which he also scored.)

Greek-born editor Mavroposaridis went to the London Film School. He wanted to be an actor but returned to Greece because there was no work in London. Back in his homeland, he studied commercials, which were his entrée into the profession that he has been working in for about 40 years. His collaborations with iconiclastic director Yorgos Lathimos includes The Lobster (2015) and The Killing of the Sacred Deer (2017), among others.

A Southern California native, Don Vito drew applause when he said he went to film school at Chapman University in Orange County. “By my senior year, I knew I wanted to edit, he declared.” While in film school, he had an internship as a post-production runner on the TV show The Trials of Rosie O’Neil (1990-1992). He worked his way up by assisting a lot of editors, including Debra Neil-Fisher, ACE.

Corwin traced his career trajectory back to New York, where he says, “I was writing plays and followed my girlfriend to New York City. I quickly realized I was a shitty writer, so I got a job as a runner at a commercial film editing house.” He worked his way up doing music videos, working with Bob Richardson, who was Oliver Stone’s DP. Corwin’s first feature experience was working on Stone’s JFK (1991) as an additional editor. He has also worked with directors Terrence Malick, Barry Levinson and Robert Redford.

Panelists took seats with the audience to watch the first film clip presented, the ending sequence from BlacKkKlansman that includes a “floating” dolly shot, which cuts to a KKK burning and then archival footage from 2017’s “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia that turned violent.

Heim said he was both surprised and delighted by the end of the film and asked if incorporating archival footage was always planned. Brown said, “No, it was not in the script,” as the film was already in pre-production when that rally happened.

He also explained that Lee informed him he wanted to use the footage from Charlottesville but told the editor not to bother looking for footage “until we get a cut that I’m beginning to feel comfortable with.” Brown showed the director a cut on January 8 (yes, he remembers the date clearly) and, at the end of the screening Lee told him to start getting the footage from Charlottesville.

“The next day Spike came in and said, ‘Do we have the footage?’ It had only been a day, but Spike was like, ‘We gotta get that footage.’ Everyday he’d come in and he’d go, ‘What’s the matter? What’s your problem? You can’t get some footage?’” Brown said Lee had his sights set on Cannes, which meant they needed a locked movie by March — Charlottesville footage included.

When Heim expressed surprise that the research hadn’t been done earlier, Brown replied, “It’s Spike… He’s got his ideas about where to put the focus of energy. He didn’t want to start thinking about Charlottesville until the moment he wanted to start thinking about it. And then [laughing] he wants it done right then. I don’t think Spike is alone in this. Many directors are impatient to see it once they have an idea.”

Brown asked the other panelists, “Don’t you think this is true?” and this morphed into a generalized conversation about patience and the director/editor collaboration.

After an extended conversation, the panelists cleared the way for the second clip of the day: the sequence of the band Queen recording the song “Bohemian Rhapsody” from the eponymous film. “It’s a spectacular sequence and visually interesting,” said Heim, who asked Ottman to talk about the sound, correctly presuming that the editor was deeply involved with it.

“I’m a sound fanatic when it comes to film, so my reward to myself when I cut a scene is to do the sound design, especially if it’s an X-Men film where you hear the humming of the machines and the ambiences; I just love doing that stuff,” Ottman said, adding that for Bohemian Rhapsody it was the more practical sound of the back-and-forth in the studio and the recording environment. He also revealed that this scene is his favorite from the film (other than the Live Aid concert scene) and that the cut that made it into the film was his first assembly.

An amazed Brown asked how that polished sequence could possibly be a first assembly. Ottman explained that he is used to making decisions early on because he’s often scoring the film as well. The editor also said he was very protective of this cut: “Like a mother crouching over her baby, I was sure someone would throw a grenade after a test screening or…studio notes. I was always very freaked out that this sequence would get messed up, but at every test screening we had it was an audience-pleaser, so it never changed.”

When Heim commented about Bohemian Rhapsody’s director Bryan Singer being fired near the end of the film, Ottman explained that Dexter Fletcher came in to replace Singer for the last two-and-a-half weeks or so, and then left to direct the upcoming Elton John biopic Rocketman. This left Ottman in charge of directing the ADR, which, he said, is not uncommon for editors to do when directors are busy or overwhelmed with other things.

In the clip from The Favourite, Abigail (Emma Stone) poisons Sarah (Rachel Weisz), who then falls off a horse and is dragged. The scene is a signature Lathimos montage, with many things taking place at once, according to Mavropsaridis. When Heim asked the editor how much of this was scripted, he explained that the montage sequence is supported by the script, but the scenes are not used in linear order.

“Lathimos respects the continuity of time and space,” so the director and editor build the early assembly and the first cut working and constructing the scenes. According to the editor, who followed with, “And then comes the moment when we start to deconstruct.”

Emphasizing that the main point of this scene is to reveal that Abigail’s true character is someone who has just poisoned another person and is not innocent, Mavropsaridis explained, “The music is very important in this scene. We start with pizzicato strings as she [Emma] is preparing the poison, then Bach [organ music] comes. These are two different pieces of music combined together. The montage creates this interplay between what is happening in the men’s room and what the real situation is.”

Heim observed how this montage built the tension. “You didn’t quite know what was going to happen — when she would fall off the horse,” he remarked. “By stretching it, it was very exciting.”

“And more poetic,” Mavropsaridis added. This lead into a conversation about the (mis)perception that editors like to make things shorter, when in fact part of editing is to “protract the action” to make more of something that was never there.

“It gives us [editors] a reason for being,” Mavropsaridis said. In the case of The Favourite, according to the editor, expanding and stretching the action is “creating something that wasn’t there. The elements were there but we figured out how to use it to make it mean something more.”

After screening a clip from Green Book that shows pianist Don Shirley (Mahershala Ali) performing, the two protagonists driving from city to city and Tony Lip’s (Viggo Mortenson) wife reading a letter that he has written from the road, Heim asked why Don Vito chose this clip.“I wanted to talk about transitions; I wanted to show something different than what people would expect,” the editor replied. “This movie is all about transitions. It’s two hours and ten minutes, and I didn’t want it to feel that long.”

As Don Vito analyzed the scene, he talked about condensing time through the use of montage and making each scene propel the story to the next scene. “There are audio transitions that help move things along. I was always thinking about, ‘How do we make this not feel like a two-hour-and-ten-minute movie?’”

Expanding on the role of the editor and how the magic of editing makes the audience not notice things, panelist Corwin offered, “This is so much a part of what we do. It is truly invisible and it’s a gorgeous way of thinking. It’s not flashy but it’s so efficient.”

Responding to his comment, Don Vito described how digital effects were used in Green Book . “You can’t see them and that’s the point; we’re not trying to be flashy,” he said, explaining that they were used remove modern-day cars and digitally replace them with cars from the 1950s. He revealed that almost 80 percent of the car shots are digital effects. When Heim, a Bronx native, asked where the film was shot, Don Vito replied, “New Orleans — even Carnegie Hall. That was actually a theatre in New Orleans and we pasted Carnegie Hall above it.”

Talk turned to the use of digital effects vs. the “olden days,” when one had to send opticals to a lab to make a transition. All agreed that in the present day, if you can imagine it, it can be done. Ottman observed, “The strange thing is the more polished it is, the less able people are to imagine something else.”

The final clip was from Vice, the story of former US Vice President Dick Cheney. The clip featured Cheney (Christian Bale) and President George W. Bush (Sam Rockwell) with fishing scenes intercut throughout the sequence. Heim asked editor Corwin where the intercuts came from. “Lynne Cheney,” he responded. “The real Lynne Cheney says if you want to understand her husband, you have to know that he’s a fly fisherman, so we had that footage.”

Corwin pointed out that he is generally associated with frenzy and frenetic scenes (The Big Short, 2015; The Tree of Life, 2011; The Horse Whisperer, 1998; Natural Born Killers, 1994), adding that on Vice he was fascinated with the silences in dialogue scenes and the lack of editorial, the subtext. “I love the fact that in film you can get into different layers of ways people are thinking,” he offered. “I think film demonstrates how quietness and cuts that don’t fit together seamlessly actually create this tension.” He added that many times seamless editing will lose the tension.

“As prospective editors — or editors — out there, you have to see where editing should be visible and where you could launch people into different layers of reality,” Corwin continued.

Before heading into the Q&A, the panelists had a lively discussion about appreciation of the editor. Harkening back to the fishing scene conversation, Corwin said, “That’s why directors hire us. Hopefully, we’ll bring another layer of consciousness to what they are doing. Many times they don’t appreciate it — or they don’t necessarily like where it is going. It many not be their vision, but I think they always appreciate that we’re out there…”

During the Q&A, the panel answered a question about working in different genres. Despite their personal genre preferences, all agreed that is essential to work in different genres so as not to become pigeonholed. On the question of how to approach a scene that needs to be in the film but doesn’t seem to be working, panelist responses were variations on changing things up, completely rethinking the scene, and working backwards from the end of the scene just to somehow “trick the mind.”

All in all, the panel was an exercise in cognitive flexibility and a delightful way to spend a Saturday morning in the lead up to the 91st Oscars. When John Ottman ultimately won the award the following evening for Bohemian Rhapsody, the camaraderie among the nominees was palpable as he shook hands with each of his colleagues before stepping onto the big stage to receive his award, before a live TV audience.