By Tris Carpenter

On the day I sat down to write this article, Apple officially unveiled the iPad. Apart from the silliness of its name, the iPad got me thinking about how far technology has come over the last 20 years. And that, in turn, got me thinking about how technology affects organizing.

I got started working for unions back in the early 1990s. My first job as a union staffer was in Massachusetts, where I was employed by a woefully under-funded UAW local, which had ten staff employees sharing two computers and three phone lines. We had over 1,500 low-wage members and tried to keep track of all their details on a Lotus (remember them?) spreadsheet. It’s astounding that we got anything done. It wasn’t until my next job, with a public employee union in Connecticut a few years later, that I e-mailed anything to anybody. Websites specifically designed for larger campaigns started in the late 1990s, but those are commonplace now. And we’ve now got IA locals using Twitter and creating Facebook pages, too.

This nifty technology is good in some ways. It allows us to communicate more rapidly, especially if we need many people to access lots of information at any time of day or night. Widespread (and relatively cheap) cell phone access has made it simpler to get a hold of people during an organizing campaign. Complex database structures allow us to quickly reconfigure data so that we can pinpoint our efforts more effectively during the heat of a campaign.

But there’s an old organizer adage that rings even more true today than ever: Flyers (or websites or e-mails) don’t really organize anybody.

As the employees build trust in each other and the Guild, the effort gets stronger and we build consensus.

I could write the best e-mail, create the spiffiest website, “tweet” the most creative 140-character message, whatever––it wouldn’t make that much of a difference. Sure, the information needs to be accessible to people; that’s the way of the world these days. But the main event, the actual act of organizing, is a face-to-face thing.

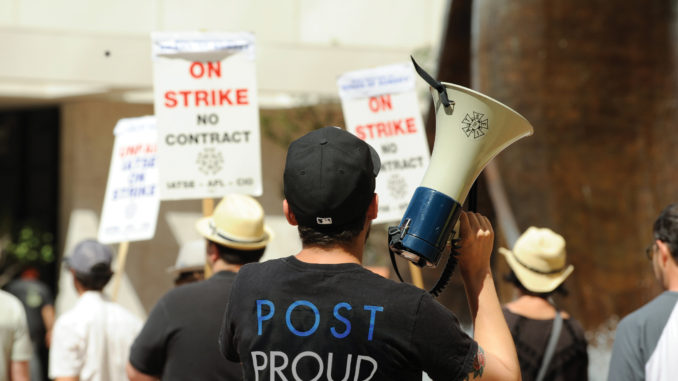

Long before we had photocopied flyers and even widespread landline phone coverage in this country, people were organizing unions. They did it by talking to each other in person. They had these meetings anywhere they could: at the worksite, in bars and coffeehouses, and at each other’s homes. Organizers from the earliest days of the craft unions in the late 1700s went to the homes of other craftspeople to talk about the idea of banding together. The Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor unions in the late 1800s were both organized by using very little paper whatsoever, but rather by word of mouth and personal conversations in homes and taverns. The industrial union organizers in the 1930s certainly didn’t have cell phones or computers; they had a car and a box of index cards to keep track of their campaigns.

We still build unions upon the personal conversations that employees have with one another. If there is some concern about talking at the workplace, we take those conversations somewhere else. If we need to go find somebody to make sure they’re included in the larger effort and we can visit them at home, we will try that. All in order to make sure that everybody is included in the conversation, and has a chance to say their piece, face-to-face. As the employees build trust in each other and the Guild, the effort gets stronger and we build consensus. And with that comes the leverage we need to get a good contract.

I like to think that I write a damn good e-mail. But much like the Tom Cruise character in Jerry Maguire, a great e-mail might get you some pats on the back, but nobody’s going to follow you out the door.