by Garrett Gilchrist

Sharp dialogue. Splintered chronology. Bursts of extreme violence. Obscure film references. Must be Quentin Tarantino, the filmmaker who burst onto the American film scene in the early ‘90s like an adrenaline shot to the heart. He won an Oscar and a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for the screenplay for 1994’s Pulp Fiction (with Roger Avary), and was nominated for an Academy Award and a BAFTA for Best Director.

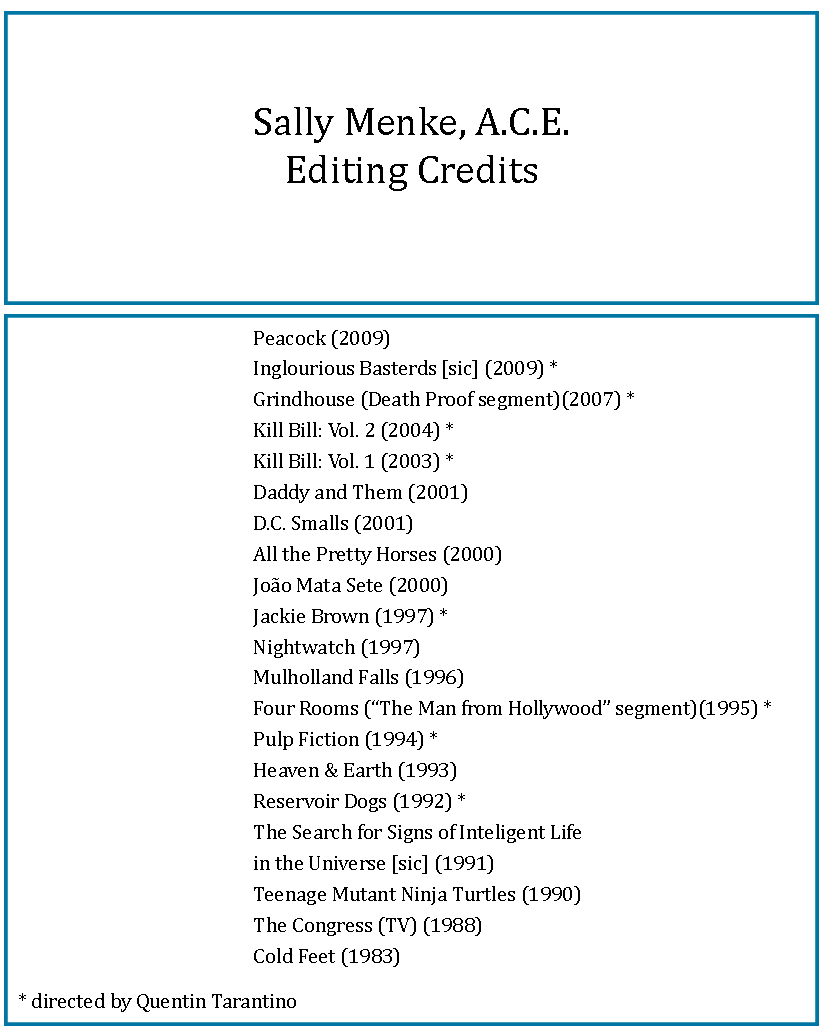

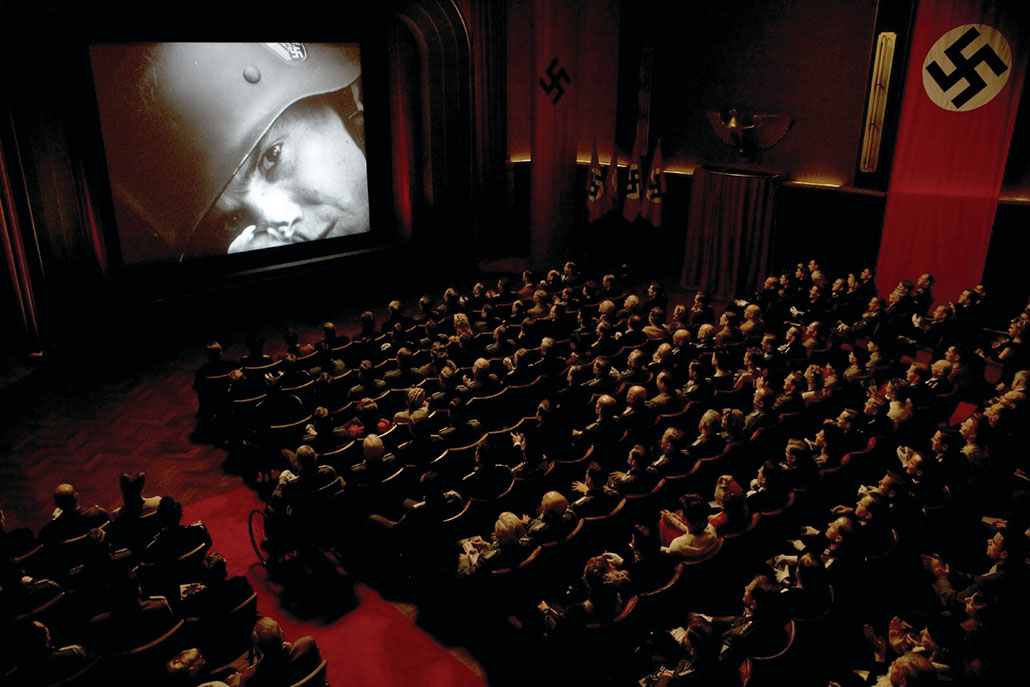

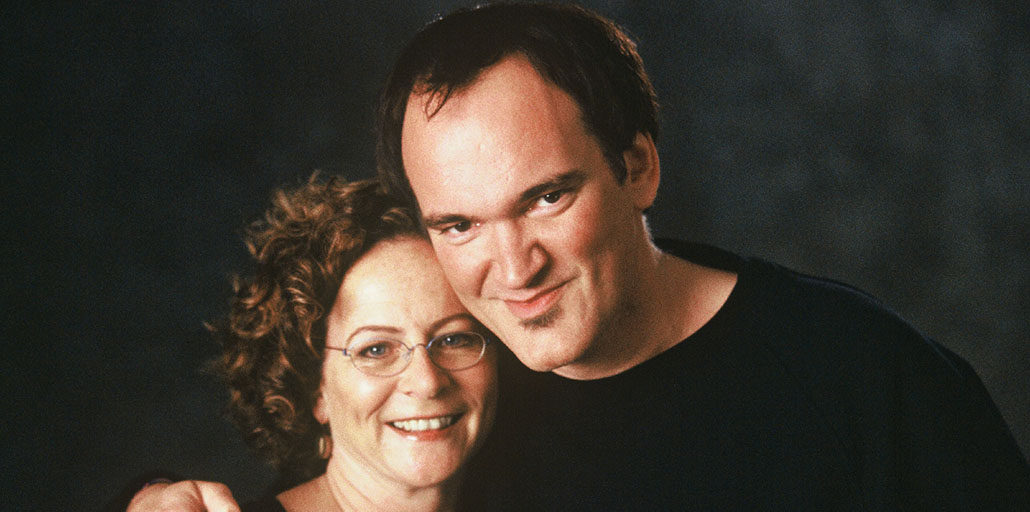

Sally Menke, A.C.E., whose editing work on Pulp Fiction was also nominated for an Oscar and a BAFTA, has been there every step of the way since Reservoir Dogs, providing the brilliantly bold cutting for all of the director’s films. Tarantino vanished after 1997’s Jackie Brown, resurfacing in 2003 with that roaring rampage of revenge, Kill Bill: Vols. 1 and 2, for which Menke received another BAFTA nomination. The pair’s latest film is one that he has wanted to make for a long time––Inglourious Basterds (yes, it’s purposely misspelled). The World War II piece follows an audacious plot to assassinate the entire Nazi high command during a film premiere. The film opened wide through The Weinstein Company August 21.

So what can you say about Tarantino and Menke, a team who have given us some of the most unforgettable images, characters and scenes in recent cinema history? A glowing briefcase. A Hattori Hanzo sword. A missing ear. A death-proof car. You could easily be forgiven for forgetting about all the fine films Menke has edited for other directors. The editor took some time out of her busy schedule to talk to CineMontage about the unique cinematic universe of Tarantino and her most recent films with him.

CineMontage: All Quentin Tarantino’s films come off as love letters to the cinema.

Sally Menke: He’ll explore as many different types of filmmaking and genres as he can. Quentin and his characters live in a cinematic world. There are a lot of films that try to hide that, but we embrace the iconography process of filmmaking. I think he likes to explore as many different types of filmmaking, and genres, as he can.

CM: In Inglourious Basterds, the power of cinema is literally used to destroy the Third Reich.

SM: It’s not history or biography. And history has been changed by Quentin Tarantino. It’s a fairy tale, once upon a time in Nazi-occupied France. It’s not history or biography. The point is that cinema is a powerful tool, and always has been. When I was starting out at CBS, I worked on a documentary about teenage pregnancy. It was such a poignant, emotional film that it actually changed policy at the White House. All films are powerful one way or another, and that power can be used for bad or good. My kids will not go to McDonald’s anymore because of Super Size Me…

CM: There’s been a lot of talk about Christoph Waltz as Colonel Hans Landa, the Jew Hunter.

SM: He is so beguiling; he’s remarkable. Quentin is brilliant at casting. When he found his Landa, he knew he needed to start shooting right away. Brad Pitt is amazing––he’s terrific in this film. It’s a group protagonist, three intertwining stories. Landa, Shoshana, and the Basterds.

CM: I’ve heard one writer criticize the final line of the film. Brad Pitt’s character says, “This might be my masterpiece.”

SM: [Laughing] What can I say? Quentin’s films are always divisive, and they’re always inspiring. There’s gonna be a lot of people who love it, and a lot who don’t like it. But I think this film really is going to hit home with a lot of people.

CM: From 1997 up to 2003, Quentin wasn’t making films at all. What happened?

SM: He was thinking about what he needed to do. I was raising my family, so it was perfect timing.

CM: You’ve worked with some great directors; Oliver Stone, Lee Tamahori, Ken Burns, Billy Bob Thornton, Ole Bornedal, Steve Barron…

SM: I love all of them. I’ve learned so much from every film and every director––a new perspective, a greater appreciation of the art. On one scene in Heaven & Earth, Oliver said, “It’s just so perfunctory.” I couldn’t figure out what he meant; then a light bulb went off in my head. It was just one cut too! I realized every single edit is important. Years ago, this documentary I was working on was a very serious piece and I made this cut that made people laugh. I realized the power of cinema.

CM: Has your relationship with Quentin changed over the years?

SM: It’s definitely grown and matured, but it’s always been as supportive and exciting as it was on day one. I understand him more fully. There’s a huge amount of understanding that’s very tacit and unspoken. It’s like living with a person, like my husband. You grow accustomed to his habits and wants, though his needs change.

We’ve been working so fast. All of us have worked together for so many years that we step right on board, knowing it’s gonna be a new ride, a different challenge, but we know how we want to do it––[supervising sound editor] Wylie Stateman and [sound designer] Harry Cohen and their whole team.; Mike Minkler, the mixer, too.

Quentin can go ahead and start doing the prefab without us even being there. And we don’t use very much ADR. We keep our team very small. I don’t like to be in a big corporate building. When I was at CBS, it was huge. It was great when I was working there, but I wouldn’t choose to work in that environment now. We like this little house, that we kind of have to squish into.

CM: Music and sound from other films are frequently referenced in Quentin’s films.

SM: Occasionally, we’ll even borrow a sound effect directly, if it’s cool and appropriate. Or an entire segment of a film, which might have music and sound effects in it. Of course 99.9% of our sound effects are new. Stylistically, creatively, we allow ourselves to write. The sound effects are never taken from another film. We’ve always created them––apart from a couple circumstances where we brought in a section of a movie that had some sound effects in it. But stylistically, yeah, absolutely! We copy other films, recreating from a similar palette of colors.

CM: You might not understand every reference, but it puts you in a specific time period and genre. Kill Bill had a vintage Shaw Brothers logo at the beginning.

SM: We study the genre we’re entering into, via Quentin suggesting films to watch, or on our own., as well as the music–– especially–– [music supervisor] Mary Ramos is our music supervisor. It won’t be from just one genre; sometimes the influences are surprising. There are some Western influences in this film––the way we cut some picture, and structured the film.

CM: A David Bowie track from Cat People is also used; anachronistic for the 1940s…

SM: Quentin’s use of music is pretty darn remarkable. He really articulates scenes with music. A lot of the choices are made early. On Kill Bill, I went into his music room and he played me a lot of music for specific scenes. He thinks very clearly about all the music, for months if not years in advance. But those moments of inspiration come from the cutting room. I don’t cut with his music before he comes in. We work together–– adjust and even edit the music to fit the filmfit certain areas.

CM: The editing of Kill Bill seems very microscopic, showing you clearly the details of what’s going on.

SM: We muse over everything for a long time. Nothing is simply connected for the sake of connecting. That doesn’t mean the film doesn’t change, but he doesn’t shoot by the hip. All directors embellish as they go along – a new idea because the actors are suddenly doing something. But Quentin really has a vision in his head, and it’s such a small group of people that we’re all able to really support his vision in one way or another. The key to good communication is to keep it intimate. It’s wonderful to find people you can work with again and again. We’re on the same page, and the control that comes from that makes for a very refined product. We’re willing to explore new approaches to making a film.

CM: Quentin often uses long takes, as in O-Ren Ishii’s parlor in Kill Bill.

SM: Bob Richardson is a brilliant DP, of course. Together they plan things really well so that it will keep an audience’s attention.

CM: A long take opens a shoot up to so much imperfection if it’s not done carefully.

SM: I haven’t had it not work with Quentin––but if it didn’t work, there’s always tricks to get around any problems.

CM: Cutaway, audio work or a special effects fix…

SM: Quentin doesn’t use CGI. We use a little bit in this new film but he likes everything to be practically composed. He doesn’t dwell on that world.

CM: Which makes Kill Bill and Death Proof work.

SM: The fighting we didn’t speed up, except for only one or two shots, which we did in camera. A lot of wire removal, but no real gadgets beyond that. The swordfights feel real. A CGI fight can just gloss over you. It feels more exciting when you can see that the people actually did it.

CM: Kill Bill blinked in and out of black and white; was that to get an R rating?

SM: It wasn’t just really for censorship. That could be a secondary reason, but we never do things without an artistic intention. The MPAA are a good group of people. We’ve had to address many things that would have lost us the R. But the blink was a decision on our part.

CM: The Kill Bill movies feel differently paced. The first being chop-socky Hong Kong action, the second a slower Western with bursts of violence.

SM: It worked out perfectly that way. The idea to divide it was there early on. A lot of story needed to be told, and it turned out that the films were so beautifully divided. We were thrilled.

CM: Death Proof embraces the Grindhouse aesthetic, with a comical use of missing footage, missing frames and leader. It looks like a beat-up old print.

SM: We’d take a pen, a needle or some other implement, and scratch the film. Nina Kawasaki, my assistant, would go out and thrash it against the bushes on the driveway. We have video of it; it’s actually kind of funny. We kept asking the lab to make this section dirtier. We never even got it; we were too careful. We should have gotten it dirtier in some places. The lab had a lot of fun, though, not being careful. Want to smoke a cigarette over that? No problem.

CM: Some critics saw Death Proof as being padded and talky to the point of self-parody, a tossed-off side project.

SM: Quentin never tosses anything off. He takes everything very seriously. It’s a film that was made with very specific ideas. Maybe we could have made it shorter, for the double feature. Since some people don’t have the patience for it. I love the film, the car chase in particular. Kurt Russell is always so great, and Zoe Bell is such a big talent. One of the nicest people on planet earth as well.

CM: How would you describe the specific style that you bring to a film? Of course, an editor’s style can differ depending on the style of the film and the director.

SM: Yes. On the other hand, I do feel there’s an internal rhythm in every person that is reflected in her or his work. Somehow a painting looks like its painter. There’s an innate response to footage that I feel is very much mine. Sometimes it’s not at all what Quentin or another director wants, so I change it. I approach the footage in a detailed way, looking at mannerisms as much as I listen to dialogue––what the body is saying.

CM: As dialogue-centric as parts of Tarantino’s films are, there is a muscular physicality to some of your edits.

SM: As long as it’s not perfunctory! I try to keep a strength of motion. I don’t do match cuts, really. That’s a ridiculous thing to say; I do. But we always explore how we can propel a scene, and that’s including dialogue, without doing match cuts, because the audience is really willing to accept a lot of discontinuity

CM: You got away with murder in Death Proof on purpose. Leader was inserted between shots that didn’t match. Did that allow you to do things that ordinarily you wouldn’t be able to do?

SM: A cut is a cut no matter what. The leader and the missing scenes didn’t simplify anything. It still was frame-perfect, in terms of our decisions. If Hollywood stops using film, poor film, but it can come back as something stylistic to do later on. Leader or a cartoon––everything’s done for a reason, to keep it strong…muscular…not perfunctory. There’s always a reason to go to the other shot. Every single frame is important, whether dialogue or action. Quentin is such a strong visionary and unbelievable auteur that it’s a pleasure each time. So what else? I was just in my little dark room…

CM: We could still find out what’s in that glowing briefcase in Pulp Fiction…

SM: We’ll never find out what’s in the briefcase.

CM: I think it’s a light bulb.

SM: [Laughing] That’s the genius of Quentin right there. It’s a light bulb––or it’s something really special.