by Ray Zone

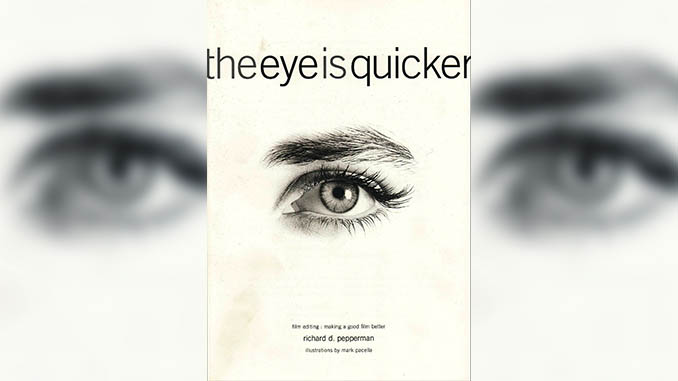

The Eye is Quicker

Film Editing: Making a Good Film Better

By Richard D. Pepperman

Michael Wiese Productions

249 pps., paperbound, $27.95

ISBN: 0-941188-84-1

Richard D. Pepperman has written a book about editing that would best stand alongside Walter Murch’s In the Blink of an Eye(Silman James, 1995) on an editor’s bookshelf. It is an aesthetic––or “psycho-aesthetic”––discussion, rather than a technical discourse, of the perceptual and psychological impact of the cut. The book gives a minute examination of the cut and its visibility and effects upon the eye. Pepperman has also been very much influenced by two other books, Andrey Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time (University of Texas, 1989) and Edward L. Dmytryk’s On Film Editing (Focal Press, 1984) in fashioning his highly philosophical examination of the dynamics of the cut.

As a film editor for motion pictures and television for over 30 years, Pepperman is highly qualified to address artistic aspects of editing. He is also the author of Setting Up Your Scenes (Michael Wiese Productions, 2005), previously reviewed in these pages, and a filmmaking instructor at the New York School of Visual Arts, where the articulation of many of the concepts expressed in this book was formulated in his work with students.

Pepperman’s title and the overriding concept for the book derived from his days as a child watching magicians on television. Reflecting on the old adage, “The hand is quicker than the eye,” Pepperman came to learn that it is not true. “The eye is quicker!” he observes and adds, “This fact is indispensable for editors. It holds a very simple significance: Directly, it means that the moment selected for the joining of images must be ‘calculated’ to the very speedy interpretive facility of our eyes––a specific cut can work well or poorly. It is equally fundamental to our ability to ‘decode’ collections of images.”

In the introduction to the book, Pepperman characterizes the ultimate goal of editing as storytelling, or more specifically, “storyshowing.” In teaching this to his students, he will frequently have them tell the story of their film projects out loud. Quite a bit of discovery results from this simple verbal tool as to the importance of structure, inflection and pacing. To question the widely held concept of the “invisible” cut, Pepperman proposed a test to his film students. In viewing a film, students were instructed to raise their hands when they observed a cut. “Not a single cut went unobserved!” says Pepperman.

“Forget precise and realistic matching of anything! What is astonishingly elastic about ‘film time’ is that the most minor modification in beats can make all the difference.” – Richard D. Pepperman

So the query is posed: “If cuts are discernible––and with very few exceptions they are––what are film editors determined to achieve?” In addition, Pepperman asks, “Are there good cuts and bad cuts? If there are, what are their attributes?” To examine this question, Pepperman analyzes many films, from student productions to major studio releases, which are illustrated in the book through black-and-white drawings by Mark Pacella with sequences of edited frames.

Using Dmytryk’s concept of the “mental hiccup,” whereby an incoming frame noticeably introduces a “sudden starkness,” Pepperman observes that such a cut is “conspicuous” and can be considered a “bad cut.” Such an edit can be improved by trimming the outgoing cut, which has “grabbed the eye,” or by adding two to three frames to the outgoing cut to extend action across the cut. Throughout the book, Pepperman has isolated “Tips” and “Hints” to underscore the salient points he is making. For example: “Tip: The ‘imbalanced blur’ bad cut can be made good by ‘seeing’ that there is a more, rather than a less, equal degree of blur on both sides of the cut. There are lots of times when an adjustment of a single frame will make all the difference.”

In noting the two-dimensional nature of the film frame, Pepperman observes, “All cuts exist within the margin of two film frames: the Outgoing and the Incoming. A cut across action must take into account another equally decisive feature of the ‘quick-eye’ reflex: How does the eye ‘read’ the spatial illusion of the projected image.” A key issue in this kind of cut pertains to the “focal point” of the eyes. With a Tip, Pepperman advises, “In all cases, if you can find the focal point––where your eyes are inevitably gaze––you can ‘find’ (or fix) a cut!” In most cases, and not surprisingly, our eyes are usually drawn to focus on the face and the eyes within the face.

While not proposing that a dissolve may be a “fix” for a bad cut, Pepperman does acknowledge that a “winning cut” is one that is inconspicuous. He also makes some cogent observations about the way in which film editing conflates our perception of both space and time.

Pepperman characterizes the ultimate goal of editing as storytelling, or more specifically, “storyshowing.”

Drawing on Stanislavsky’s concept of breaking down a scene into tiny moments or “beats,” he proposes a bold strategy: “Whenever ‘real-life’ time (or space) is a primary editing pursuit, you will be risking far more (serious) audience confusion than if––through beats––you establish a sense––or texture––of the needed (psychological) time.” He offers strong advice to forget about matching action over the cut but also advises to “forget precise and realistic matching of anything! What is astonishingly elastic about ‘film time’ is that the most minor modification in beats can make all the difference.”

Editors will rejoice in the epigraphs that open the 22 chapters in this book, with commentators ranging from Isaac Bashevis Singer to Walter Pater, who observes, “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music.” Pepperman’s book is a bracing invitation to revisit the art of motion picture editing with new eyes.