by Ray Zone

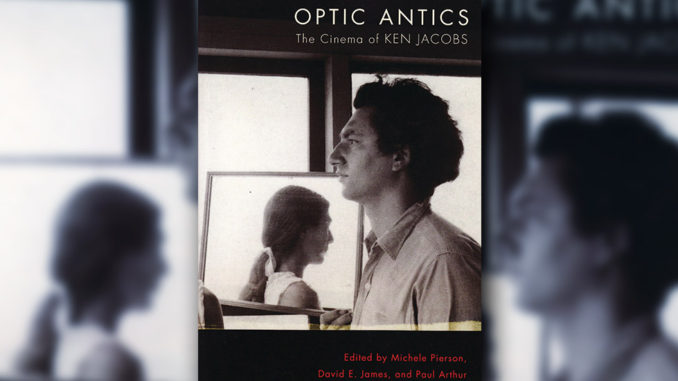

Optic Antics:

The Cinema of Ken Jacobs

Edited by Michele Pierson, David E. James, and Paul Arthur

Oxford University Press

Softbound, 294 pps., $39.95

ISBN: 978-0-19-538498-7

I’m not sure how many industry professionals in Hollywood know who Ken Jacobs is. Let me tell you. Ken Jacobs has been making avant-garde, experimental or underground films in New York City for over 50 years. With over 30 film and video works, Jacobs has also created many shadow plays, magic lantern performances, art installations and sound pieces that deal with film, cinema history and the nature of the moving image. His works have been canonized in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) and the Whitney Museum of American Art, which included him on its list of “100 Greatest Artists of the 20th Century.”

Even though extensive discussion has been given to Jacobs’s work in seminal books like The Underground Film by Sheldon Renan (E.P. Dutton; 1967), Underground Film, A Critical History by Parker Tyler (Grove Press; 1969), Experimental Cinema, A Fifty-Year Evolution by David Curtis (Universe Books: 1971) and Visionary Film, The American Avant-Garde, 1943-1978 by P. Adams Sitney (Oxford University Press; 1974, 1979), the present volume, a rich compendium of essays, is the first to be solely dedicated to Jacobs’ cinema.

Jacobs may be best known for his six-and-a-half-hour magnum opus Star Spangled to Death, which he first began filming in 1956. In her introduction to the book, Michele Pierson characterizes the film as “an epic junk collage,” in which Jacobs edited found footage and filmed performances together. “Out of this recycling of junk materials,” writes Pierson, “Jacobs developed an avant-garde aesthetic that eschewed technical perfection and professionalism and exposed the haunted contents of consumer culture’s castoffs.”

In his essay on Jacobs, Paul Arthur notes that the filmmaker creates “spectacle from dross” and observes, “It is hard to imagine another filmmaker as willing to court disaster both in the making and presentation of his work.” Arthur adds, “Lurking at the edges of Jacobs’ myriad improvised, rehearsed or aleatory maneuvers is an impossible pursuit of presentness in the screened image, which is, for him, always ripe with time, with oscillating layers of past and present. His trashing of linearity summons a temporal realm that is often surprisingly historical in effect, but can nonetheless yield an apocalyptic scent of something beyond time––a secular machine-made version of eternity.”

“The challenge for the artist, as Hofmann saw it, was to render space as movement, as the penetration of one moment into another; in a word, to render it in time.”- Michele Pierson

With this highly poetic observation, Arthur is also commenting about Jacobs’ “Nervous Magic Lantern” performances of projected imagery using a complicated device of his own invention. These performances create a hallucinatory, non-objective inference of spatiality, a trance-like cinematic experience unlike any other. The “historical effect” in Jacobs’ work can be seen in his 1969 appropriation of Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son, which avant-garde theatre pioneer Richard Foreman describes as “a lengthy re-photographing and total alteration of speed, focus and exposure with selective zooming in on the image to ‘pulverize’ it into graininess.” Jacobs’ extended deconstruction of Billy Bitzer’s 1905 Edison short centers on the filmmaker’s “choices of what to see, what to alter, how much and for how long. One might object; but isn’t this akin to choices all artists make?” In 2008, Jacobs produced a two-hour anaglyphic 3D version of Bitzer’s film.

For Jacobs, art-making is a highly political act. He is a cinematic “fly in the ointment” of motion pictures, a challenging “conscience” for the medium. Foreman rightly observes that Jacobs, by the act of editing Blonde Cobra, a 1963 underground classic he made with Bob Fleischner and Jack Smith, became the “creator” of the film, an essentially moralistic action. “This invocation of a universe in which moral choice is central is so placed in the film [by its editor, Jacobs] that I think it can be seen as the ‘open sesame’ of all of his work,” writes Foreman.

Jacobs had a university teaching career in New York for 33 years, developing innovative curricula that enabled students to major in independent filmmaking within the context of a liberal arts program. Jacobs’ teaching style, as with his art, is confrontational and discursive. Pierson notes that when Jacobs first began to screen Tom Tom in 1969, it “was especially important for the development of a critical vocabulary for engaging with the formal challenges” of cinema. “Beyond the influence of this landmark film on avant-garde filmmaking and critical writing on the avant-garde,” Pierson writes, “Tom Tom has also helped to change the way that film scholarship, more broadly, looks at early cinema.”

For decades, Jacobs has also explored stereoscopic aspects of cinema and how we see the motion picture image, inferring depth from a planar screen. This is not surprising in that he was inspired early in his career as much by the painter Hans Hofmann as cinema itself, with all its temporality. The act of filmmaking, for Jacobs, is an interrogation of both space and time.

“When he talks about what he learned from Hofmann, Jacobs most often talks about how Hofmann’s teaching provided him with a context for exploring ideas about space,” observes Pierson. “As it was for the cubists, the challenge for the artist, as Hofmann saw it, was to render space as movement, as the penetration of one moment into another; in a word, to render it in time.”