by Kevin Lewis

Though Leni Riefenstahl created the artistic principles for documentary direction and editing with Triumph of the Will (1935) and Olympia (1938), her notoriety as Adolf Hitler’s filmmaker ostracized her in the international film industry till the day she died at 101 in September 2003. In the few interviews she granted in those seven decades, she always denied she was a Nazi propagandist, stressing that she was a naive artist rather than a political opportunist. Two recent biographies, Leni: The Life and Works of Leni Riefenstahl (Vintage) by Steven Bach and Leni Riefenstahl: A Life (Faber & Faber) by Jurgen Trimborn and Edna McCown (translator), have unearthed damning evidence that she was a narcissist Nazi diva who legitimized the Nazi ideals of force and physical beauty through the power of her images.

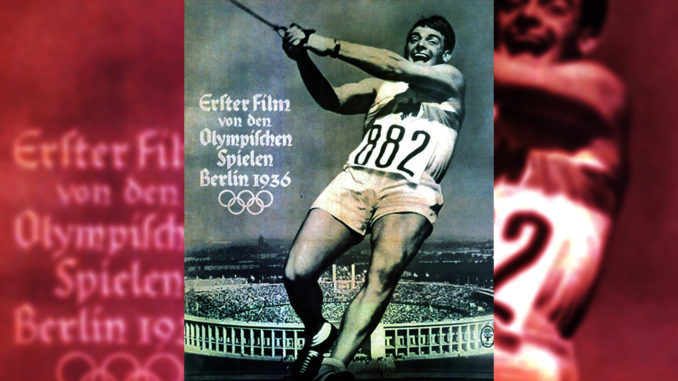

Olympia, which chronicled the 1936 Olympics in Berlin and was released 70 years ago this April, is actually two films: Olympia Part One: Festival of the Nations and Olympia Part Two: Festival of Beauty. It retains its pantheon stature and is still regarded as the greatest Olympics and sports movie. It eclipses Tokyo Olympiad (1964) and Visions of Eight (1973), the latter of which took eight directors to chronicle the 1972 Munich Olympics.

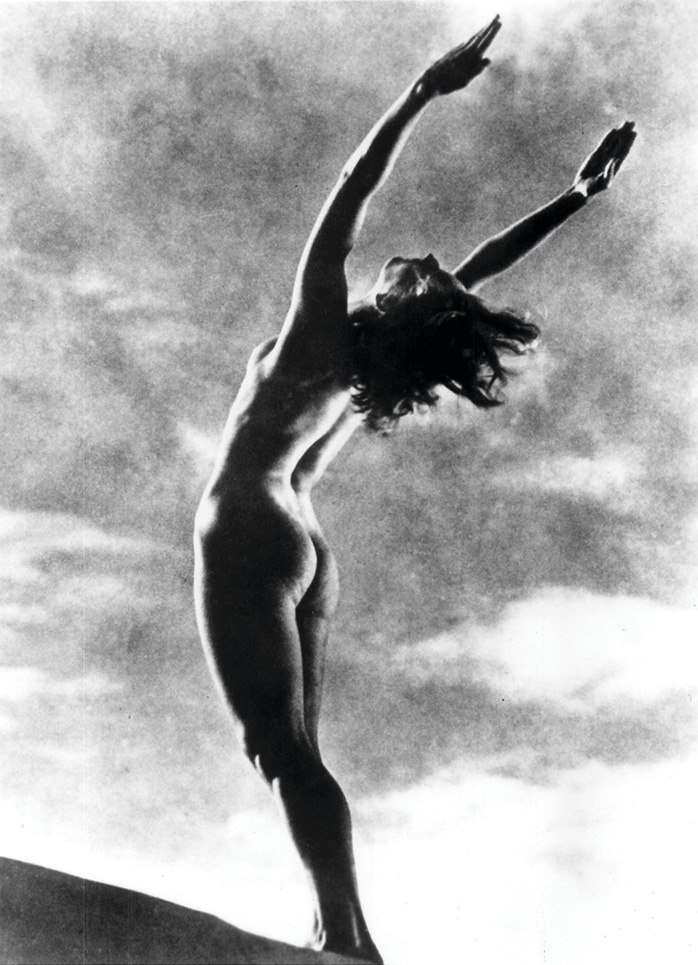

Riefenstahl’s directorial and editing decisions are implemented today by every director of sports programming on television, who ape her style of photographing athletes as classical statuary. The diving sequence in particular has been replicated on countless sports programs. The prologue of Olympia Part One: Festival of the Nations is set in ancient Greece, with its torch run and lighting, and climaxes in 1936 Berlin. It neatly juxtaposes the 20th century athlete with the ancient Greek counterpart. The torch run is an eagerly watched part of every subsequent Olympic opening ceremony.

Riefenstahl, who was a dancer before she became a movie star in Weimar-era mountain climbing films (including her first directed film, 1932’s The Blue Light/Das Blaue Licht), responded to the autoeroticism of sports. By photographing nude male and female athletes for the classical sections, she not only lent a sensual and timeless quality to sports, but also emphasized the Nazi obsession with neoclassical architecture, public sculpture and physical culture. Riefenstahl herself was an athlete who pursued deep-sea diving and underwater photography well into her 90s. It could be argued that her attraction to Nazism was rooted in autoeroticism and the sexual nature of the warrior and the athlete. Hitler recognized these qualities in her and authorized her direction of Triumph of the Will, a staged documentary of the Nuremberg rally of 1934.

Olympia is still regarded as the greatest Olympics and sports movie.

According to Bach, the film was financed by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda, and not Dr. Carl Diem from Germany’s Olympic Committee, the story Riefenstahl always told. Goebbels gave her a lavish budget of 1.5 million reichsmarks. Riefenstahl photographed the 1936 games from dirigibles, balloons and light planes. “Automatic cameras were cushioned in rubber and fastened to horses’ saddles or were suspended in tiny baskets from the necks of marathon runners and aimed at their feet as they pounded concrete roadways,” writes Bach. “Trenches were dug for low-angle views; steel towers erected for high.”

She initially enlisted the expertise of Dr. Arnold Fanck, who had filmed the 1928 Winter Olympics at St. Moritz and was Riefenstahl’s director on The White Hell of Piz Palu (1928) and S.O.S. Iceberg (1933). Although an estimated 20 editors were involved in the post-production process of whittling down 1.3 million feet of film for Olympia, Riefenstahl claimed sole credit in a succession of memoirs and interviews. Ultimately 70 percent of the footage was unusable. The recent Pathfinder DVD, Olympia: The Complete Original Version, strives to be the definitive archival version, complete with deleted scenes, but Riefenstahl made the film in at least three versions (German, French and English) and re-edited the almost four-hour film for commercial and ideological reasons for various markets.

With Michael Delahaye for Cahiers du Cinema in 1965, she discussed the year and a half she spent in her glass-partitioned editing rooms. On each side of the partitions she hung filmstrips. “I suspended them one next to the other, very regularly, and I went from one to the other, from one partition to the other, in order to look at them, compare them, so as to verify their harmony in the scale of frames and tones,” Riefenstahl said. “As a composer composes, I made everything work together in the rhythm.” She also recognized the balance between sound and picture. “Is the image strong? The sound must stay in the background. Is it the sound that is strong? Then the image must take second place to it,” she continued. “This is one of the fundamental rules that I have always observed.”

The decision was made to hold the premiere on Hitler’s 49th birthday on April 20, 1938. The film was to be used as a propaganda tool, so Riefenstahl brought the film to the United States in November 1938 with sponsorship by Avery Brundage, a Nazi sympathizer, an America Firster and President of the United States Olympic Committee (USOC).

That month, Kristallnacht, the pogrom against Jews in German cities, stirred the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League for the Defense of American Democracy to take full-page advertisements denouncing her appearances. “There is no room in Hollywood for Leni Riefenstahl! At this moment, when hundreds of thousands of our brethren await certain death, close your doors to all Nazi agents. Let the world know. There is no room in Hollywood for Nazi agents!!” the ads warned.

When asked by a San Francisco Chronicle reporter about Kristallnacht, Riefenstahl stated, “There are four walls about me…when I am at work. I work always. It is not possible for me to know what is true or what is a story.” Incredibly, she weathered this bad publicity with the support of Brundage, Harrison Chandler, son of the owner of The Los Angeles Times, and William May Garland of the American Olympic Committee in Los Angeles. They sponsored a screening of Olympia at the California Club in Los Angeles on December 14, but the only notable movie star who attended was Johnny Weissmuller, the Olympic medalist-cum-Tarzan. This screening was reviewed by The Hollywood Citizen-News with this endorsement: “the finest motion picture I have ever seen…its only message is the joy and the glory that comes from the development of a superb body.” The Los Angeles Times emphasized that it was “in no way a propaganda production.”

The motion picture community––with the notable exceptions of Hal Roach and Walt Disney–– shunned Riefenstahl because of a massive telephone campaign against her. A chilling correspondence from Garland to Brundage survives that states: “The Jews of Hollywood are hostile to Leni… Well, time marches on and perhaps some time in America they may get what is coming to them.”

Riefenstahl’s film career peaked with Olympia because she clashed with Goebbels over her demand to film the Polish Campaign and travel with Hitler during World War II. Her next film, Tiefland, begun in 1940 but not completed until 1954, was her swan song. She narrowly missed being convicted of war crimes and spent much of her remaining life as a photographer of the remote African tribe of the Nuba, a far journey from the glory of the Olympics and the tumult of Nazi Germany. The Nuba reside in the Sudan, which, ironically, is now undergoing its own genocide.