by Edward Landler

In The King of Comedy (1983), directed by Martin Scorsese from Newsweek film critic Paul D. Zimmerman’s script, fledgling comic Rupert Pupkin wants to be a star. Obsessed with celebrity itself, he emerges from the subculture of fandom to take a shot at fame by kidnapping late night talk show host Jerry Langford. The ransom for the star’s release: Pupkin must first appear on Langford’s nationally televised show performing his comedy routine.

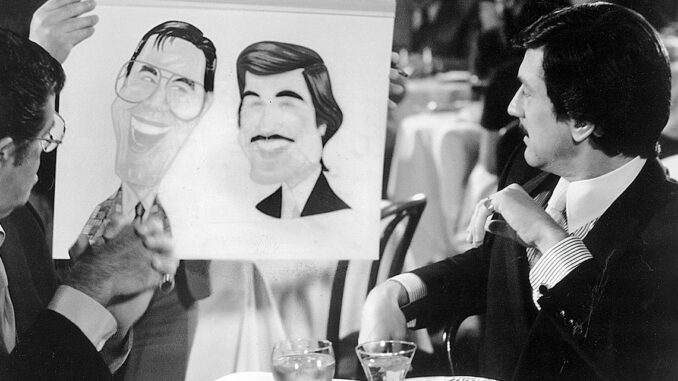

Opening in New York City on February 18, 1983, The King of Comedy was greeted with anxious anticipation. Scorsese’s star and winner of the Best Actor Oscar for his previous film, Raging Bull (1980), Robert DeNiro was playing Pupkin. Playing opposite him was the legendary comedian/actor/writer/director/producer/TV variety show host Jerry Lewis as Langford.

20th Century-Fox Film Corporation/Photofest

Just two months later, in April when the Cannes Film Festival announced the selections for its 1983 edition, The King of Comedy was slotted for its May 7 opening night gala. (Back then, every film at Cannes was not a premiere.) For the French, the collaboration among their revered comic auteur Lewis, the rising young auteur Scorsese and the brilliant method actor DeNiro was a cinematic event of historic proportions.

In Ronald Reagan’s America, 35 years ago, however, the movie’s satire of the media’s emerging mixture of real life and entertainment struck uncomfortable notes. Despite some favorable reviews and fair box office returns in New York and Los Angeles, the picture earned less than $2 million in its first weeks of release. By the time Cannes made its selection, 20th Century-Fox was pulling the film out of US distribution.

In 2013, for its 30th anniversary, the movie was restored digitally in 4K from the original camera negatives and screened on April 27 for the closing night of the Tribeca Film Festival (co-founded by DeNiro). On stage afterwards, Scorsese, Lewis and DeNiro joked about the shoot and talked about how the film had held up over time. According to a Huffington Post article the next day, the director noted, “We knew we were commenting on the culture of that time, but not thinking that it would blow up into what it is now.”

Two months before Tribeca, in an article about The King of Comedy in the British film magazine Empire, Sandra Bernhard, who played Pupkin’s partner in crime, Masha, in her first major film role, pointed out, “It was ahead of itself in exposing what motivates our whole culture. Everyone wants to be near the immortals.”

Zimmerman got the idea for the screenplay in 1969 while watching host/producer David Susskind’s interview show on New York’s educational public broadcasting channel WNET. The subject being discussed was “Celebrity Chasers and Autograph Hounds.”

20th Century-Fox Film Corporation/Photofest

In Mary Pat Kelly’s book, Martin Scorsese: A Journey (1991), Zimmerman said, “I was fascinated by the intimacy with which autograph hunters spoke of these people they didn’t really know.” Seeing a connection between autograph hunters and assassins, he added, “Both stalked the famous.” The scriptwriter was also influenced by an Esquire article about a man who kept a nightly diary analyzing every one of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show broadcasts.

Early in the 1970s, Zimmerman took his treatment to Milŏs Forman and they collaborated on a script until the director dropped it to work on One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). The writer completed his own draft and, in 1974, showed it to DeNiro and Scorsese at the Cannes Directors Fortnight, where their film Mean Streets (1974) was being screened.

At the time, the director dismissed it as “a one-gag film,” as he admitted to The New York Times in 1983, but DeNiro liked it well enough to option the screenplay for himself. Four years later, his Deer Hunter (1978) director, Michael Cimino, signed on to the project and DeNiro secured a $10-15 million investor’s deal with producer Arnon Milchan. When Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980) failed at the box office, DeNiro tried to get Scorsese interested again after the release of their critically acclaimed Raging Bull.

With a sense of his own growing fame, the director now saw more in the screenplay — as he told the Times, “I can identify with Rupert Pupkin.” Retaining Zimmerman’s structure and much of the dialogue, he and DeNiro revised the 1974 draft to reflect a darker perspective on a story that its original writer had seen as a fantasy.

The writer explained, “Marty and Bobby are realists. They made it much better, much deeper, tougher, more important.” He had seen Rupert as a Danny Kaye-like figure and Masha, his accomplice, was, he said, “weepy and sentimental,” adding, “Marty gave her that predatory quality.” The only character added to the script was Pupkin’s mother, heard only in voiceover, played by Scorsese’s own mother, Catherine. Zimmerman still got full credit for the script — as had Paul Schrader for Taxi Driver (1976) and Mardik Martin for Raging Bull — despite rewrites by the director.

While the project was being prepped, current events at the time lent even more relevance to the script. John Lennon was shot and killed by Mark David Chapman (who wanted to be famous) on December 8, 1980; and the Oscar ceremony that gave DeNiro his golden award the following March was postponed a day because of the attempt on President Ronald Reagan’s life by John Hinkley, obsessed with Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver, in which DeNiro starred.

20th Century-Fox Film Corporation/Photofest

NBC icon Carson was fittingly offered the part of the talk show host, originally named Bobby Langford, but he turned it down. Working on the fly five nights a week on TV, he had no interest in doing any kind of show that required multiple takes. After considering Orson Welles, Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin for the part, Scorsese sent the script to Lewis, Martin’s former partner.

“He understood it without even reading it,” Scorsese recalled in the aforementioned Empire article. “He knew it inside out.” Lewis even insisted that Langford’s first name be changed to Jerry. Invoking method acting, DeNiro called Lewis to tell him that they had to maintain the same personal distance as their movie characters and they must have no social contact until the shoot was over.

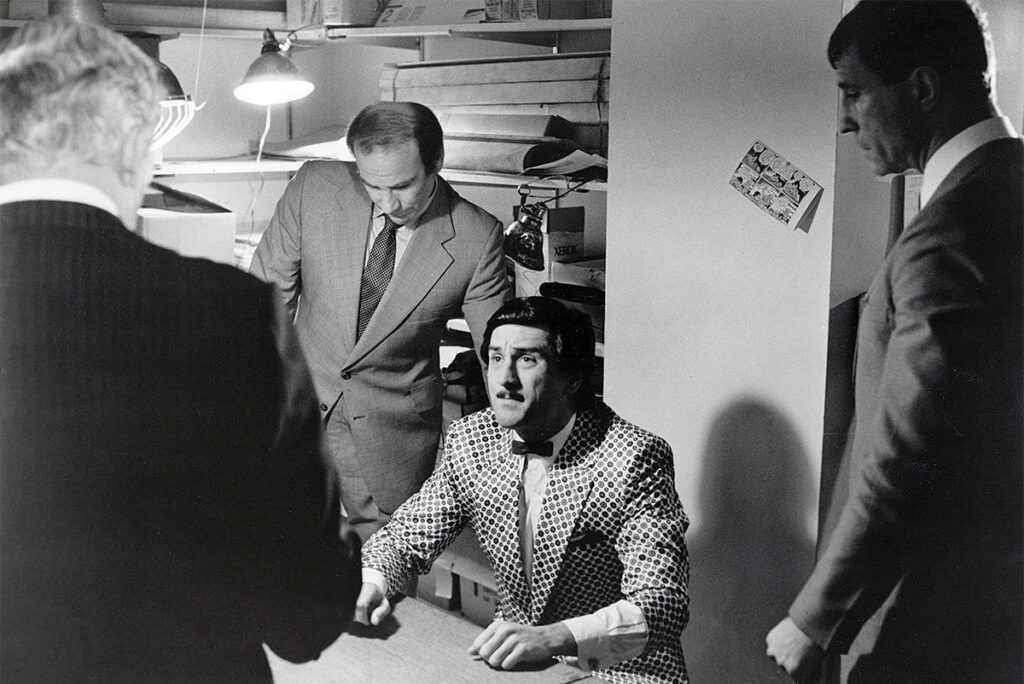

Pupkin’s apparel might also be attributed to the method. Window shopping on Broadway with costume designer Richard Bruno, DeNiro espied what became the wannabe comic’s red suit and red bowtie adorning a mannequin. The mannequin even sported the pencil-thin mustache the actor adopted for the role. As the talk show host, Lewis simply wore clothes from his own personal wardrobe, and his own dog was Langford’s dog.

Seeking authenticity for “The Jerry Langford Show” itself, set decorators George DeTitta, Sr. and Daniel Roberts based their sets on floor plans and photographs of the offices and staging areas of both The Tonight Show and The Merv Griffin Show. Familiar talk show figures were featured in talk show scenes, including Victor Borge, Dr. Joyce Brothers, announcer Ed Herlihy and bandleader Lou Brown. Even Tonight Show producer Fred De Cordova agreed to portray the fictional show’s producer; Scorsese played the show’s director.

Typecasting was central in a scene prior to Pupkin’s spot on the missing Langford’s show, now guest hosted by Tony Randall. The scene was played entirely with non-actors doing their real-life jobs — producer De Cordova, an FBI agent, and the filmmaker’s own lawyer and agent. “They really fought,” Scorsese told The Village Voice in a 1983 interview. “When I yelled ‘Cut,’ they kept on going.”

Still recovering from pneumonia caused by the stress of making Raging Bull, the director planned an easy shoot in his native New York City with a simpler visual style — “more like Edwin S. Porter’s The Life of an American Fireman [1903], with no close-ups,” he told film critic David Thompson for the book Scorsese on Scorsese (1989). The start date was set for July 1 with cinematographer Fred Schuler, ASC, who had been camera operator for DP Michael Chapman, ASC on Raging Bull and Scorsese’s concert film with the Band, The Last Waltz (1978).

A possible work stoppage due to a threatened directors strike forced producer Milchan to move the shoot up a full month to June 1, with intense summer heat already setting in. In a Film Comment interview, Scorsese said, “I wasn’t in very good physical shape at the time and I had very great difficulty shooting every day.” Sometimes he would only shoot from about four in the afternoon and quit by eight that night, only managing to do four or five setups.

Major scenes requiring improvisation also slowed things down. “We got into a rhythm where we’d go through maybe 22 takes, sometimes more,” Scorsese noted in Martin Scorsese: A Journey. “I recall doing 40 takes on some scenes.” One totally ad-libbed scene provoked real anger in Lewis’ performance as Langford was being confronted by Pupkin at the star’s Long Island estate, when DeNiro launched into blistering anti-Semitic taunts (not heard in the finished film). Similarly effective was Scorsese directing the quirky, in-your-face Bernhard to make Masha a “sexual terrorist” when she holds Langford hostage in her townhouse.

Recognizing how he had tried the veteran comedian’s patience during production, DeNiro praised Lewis for stepping in to correct speech rhythms during the filming of the TV show scenes. Scorsese offered, “He helped with intangibles, like body moves. I purposely did long takes on him so I could study him,” according to a New York Times article published in 1981.

20th Century-Fox Film Corporation/Photofest

After a 19-week shoot, production wrapped on October 21, 1981. Over the following 11 months, Scorsese cut the picture in his Manhattan triplex with editor Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE, who was also the picture’s production supervisor, and had recently won her first Oscar for Raging Bull. She has edited all of Scorsese’s features since.

Starting out, progress on the cut was painfully slow. In the book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (1998), about the “movie generation” filmmakers, Scorsese explained to author Peter Biskind, “It was partly because I shot so much footage — almost a million feet of film I had to sit through… I just couldn’t do it.” Also contributing to his “editor’s block” from November 1981 through March 1982 was the breakup of his three-year marriage to actress Isabella Rossellini.

More than the fervent exhortations of DeNiro, Milchan and Schoonmaker, a real-life event may have gotten the director back to work. On March 15, Theresa Saldana, who played a major supporting role in Raging Bull, was savagely stabbed outside her West Hollywood home by an obsessive fan.

Scorsese and Schoonmaker continued to work through October mainly at night. For the book Conversations with Scorsese (2011), the director told film critic Richard Schickel, “Raging Bull was edited only at night, so nobody would call us. The King of Comedy was edited at night, and we got into a rhythm. That’s when making a film is really the most fun.” The Band’s Robbie Robertson produced the soundtrack for the film, a mix of popular music and orchestral score.

At completion, the budget for the movie came to $19 million; it eventually grossed $2.5 million.

Even though The King of Comedy died at the box office, it got some attention in awards season. While getting no Oscar nods, it received five BAFTA nominations — including for Actor (DeNiro), Supporting Actor (Lewis), Direction (Scorsese) and Editing (Schoonmaker) — with Zimmerman winning the British Film and TV Academy’s original screenplay award. The London Critics Circle Film Awards named it Best Picture, and Bernhard was named Best Supporting Actress by the National Society of Film Critics in the US.

Today, unscripted television seems to have merged almost completely with the media’s portrayal of events directly affecting society and culture on a day-to-day basis, and The King of Comedy’s portrayal of the ordinary people and their regard for celebrity rings truer than ever. Pupkin’s pointed yet obsequious hostility nags and resounds within us just like any bully’s jarring gibes.

In the Empire article five years ago, Bernhard nailed it: “Today, the immortals are the stars… People get angry because they can’t have that kind of rich and famous success and beauty. It’s a real double-edged sword of ‘I love you,’ ‘I hate you.’”