By Scott Essman

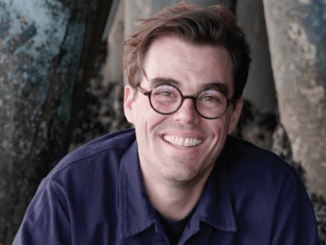

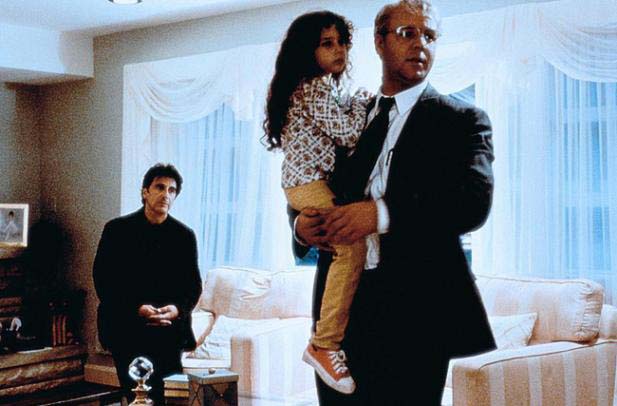

Based on a real incident from the early 1990s, The Insider is Michael Mann’s newest feature after scoring critical successes with films such as Heat, Last of the Mohicans, Manhunter, and Thief. Starring Al Pacino as 60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman, Russell Crowe as whistle-blowing tobacco scientist Jeffrey Wigand, and Christopher Plummer as 60 Minutes Mike Wallace, the movie features a tantalizing human drama, played off of the parallel stories of Wigand and Bergman. For the editing team, The Insider represented a formidable example of overcoming the challenges of working with a passionate fastidious director to realize his vision. To do so, the editors’ collective tenure on The Insider was staggering – lead editor Bill Goldenberg worked for a year, Paul Rubell for 14 months, and David Rosenbloom for five months. Needless to say, their efforts are all onscreen – The Insider is a two-hour thirty-seven minute engrossing experience that evokes the craftsmanship of classic 1970s cinema.

Why did Michael Mann choose to have three editors on this film?

Paul Rubell: Michael’s roots are executive producing TV series like Miami Vice – of which David cut the pilot – and I think he loves the action of having three shows in various stages of completion with editors working down the hallway on a variety of shows, with some stories in development and others getting ready for air. I think, consciously or unconsciously, he probably tries to recreate that same buzz when he is editing a feature.

Since this was based on a true story, did you feel compelled to research the facts?

David Rosenbloom: You become informed by the material and you learn what you need to know from it. The movie itself is pretty descriptive and has its own point of view, so while it is documentary-like in the way it was shot, we’re not necessarily educating the audience beyond how the story educates.

Why did only two of you stay on for the entire length of the project?

DR: When I left [at the end of 1998], this picture was in pretty good shape and at that point, Michael felt that there wasn’t necessarily enough work for three editors. It was into a very good form – pretty close to what got released – then the post production sound work began. Michael just felt that three was too many – he was right.

“What keeps you going is that Michael makes movies that are about something at a level in which very few directors operate.” – Bill Goldenberg

The Insider, while not a political film, addresses many issues – capitalism, power, and corporate decision-making, among others. Do politics enter your decision to do a film?

PR: If you object to the politics, then you don’t take the job. But your role as an editor has nothing to do with your personal opinions. You’re there to make the best possible version of that movie that it can be.

How was it determined which of you edited the various sequences in the film?

Bill Goldenberg: It is interesting that on Heat [Goldenberg was the only member of The Insider’s editing team to work on Mann’s 1995 film, Heat – Ed.], Michael was very specific about who cut what scene. He felt like each editor had their strength and he assigned the scenes, but on this film, I think he felt comfortable with all three of us cutting anything – he felt that we were all equally ready for any scenes. When we once got the movie into a first cut, then we decided we would divvy it up more logically, so that we each had longer stretches of the film.

PR: We had a very specific method: we’d just take whatever comes up in the rotation. Just grab it off the shelf and cut it. And then, as you get further along, if there are a couple of scenes to choose from, you take the one that might link up to yours so that you have a bigger section with more of a flow. But basically, it is just chance.

We had a team of Avid assistants and a team of film assistants. At the end of every day, we would turn over the scenes that had changed to our Avid assistants and they would then conform the Avid cut. They would then handle the necessary change notes to the film assistants in the film department who would then conform the work picture. Michael likes to screen the movie a lot, sometimes, on a daily basis, and at least every other day, which, if you are editing on film is a relatively simple thing to do. It’s much more complicated and time consuming when you are working on the Avid.

What would transpire among Mann and the editors during the dailies?

PR: Michael’s method is to watch them and dictate into a micro cassette recorder a stream of consciousness [report] of everything he is thinking. It then gets transcribed and put into a book, a copy of which each of us has. This became the bible, and he would constantly refer back to his first impression because he knows that the longer you look at something, the less objective you are. He would work the same way with regards to the cut; each successive cut would be put onto tape, sent to him, he would view it, dictate his notes, and then we would get back his transcribed notes, which is a great way to work. He also did that with sound notes. On the dubbing stage, he was very hands on; he mixed most of the music in the movie himself. He would then screen the movie and dictate his reactions. He would fiddle with levels during the screening, note the levels on the page, and then those would be transcribed. The next day [the sound team] would come back to the dubbing stage and they’d recreate those moods.

With such a hands-on approach, does that leave you any room to be creative?

PR: Michael has the ability to set the parameters and then let his people fill in the blank spaces. I think a prime example of his courage in doing that is the way this movie was shot – the camera work is kind of chaotic. It is the opposite of what you would call a controlled visual style. The camera is always moving and it is very jittery and when you look at the dailies, you see that the operators had great latitude in what they could physically do with the camera; they tried some wild things and Michael loved that. He would sort of control the chaos and shape it, but he allowed the chaos to occur.

BG: He did something that is similar to live television on this movie, where each cameraman had headsets and he would speak to them during the shot. He would make adjustments during the takes which I am assuming that other people do, but it was the first time I had seen it in a feature.

DR: I never worked with a director who gave such precise notes – the fact that the notes were precise and that there were so many of them made them imprecise because you couldn’t possibly do everything that the note said to do. If you did, you would have 24 versions of the scene. The notes provided you with a road map and oftentimes the chaos in the editing was trying to figure out the one way that you could first put the scene together. Although there were versions upon versions, the first step was try to figure out what Michael wanted and which note might supersede the next. Ultimately, you could only arrive at one destination. So, on the typical day, we would share each other’s notes, then see if we achieved the note.

“You can give greater meaning to lines through editing than exists initially.” – Paul Rubell

BG: I think that most times, you try to figure out the spirit of the note as opposed to doing specifically what the note said.

PR: We also agreed at the outset to grant each other the freedom to criticize each other’s scenes in making the film stronger and so, we would approach it in the spirit of total camaraderie and would make suggestions about each other’s scenes and just set our egos aside. Michael doesn’t want to sit down and have a theoretical discussion about a scene. His metabolism works too fast for that, but he loves it if you just cut a different version of a scene and show it to him. That is why I say he communicated to us by memo and we communicated with him by tape because a picture is worth a thousand words.

How closely did the notes follow specific items from the dailies?

BG: He would sometimes watch dailies eight hours at a stretch, commenting on every line and taking it all in, not missing a thing, remembering moments like the way the light hit Russell Crowe’s eye in a certain take. He would just remember it months later. Also, Michael has the unique ability to watch the movie every other day, and see it as fresh as anybody I have ever seen. He is able to look at it like he has just seen it for the first time or hadn’t seen it in a long time. It is a unique ability to maintain distance when you see the movie four or five times a week.

His attention to detail and accumulation of it is like nothing I have ever seen before. I have done two films with him and he really feels like the small things add up to the whole, and he doesn’t want to let one of those small things get by without making sure it is perfect.

If there is a moment of complacency, Michael feels like the movie is not getting better. At the point where he relaxes, takes a breath, he feels that there is something we could be doing.

With a film so dependent on performances, can you manufacture key moments in the story when you’re in the editing room, or does it have to come from the footage you are given?

DR: I think the more movies are manufactured in the editing room from scene to scene to scene speaks to the problems inherent to the script than the creativity of an editor or the director in the editing room.

PR: You can give greater meaning to lines through editing than exists initially, so you’re not so much manufacturing with shots from other scenes, but you’re manipulating the dialogue to create a greater importance in certain lines than ever existed. The reason or need for that importance in the line comes to light after you see the movie as a whole than when you are just viewing the scene. The scene works differently, obviously, in the context of the picture than it does by itself. So you work on it once by itself to make the scene work, put it into the body of the picture, and you realize you need to get other values out of it. At that point, you begin to go in, take the line, and reorder the sequence of lines to get the meaning that is more germane to the picture than to the scene.

Is there any extra pressure on you as editors when you are cutting a scene with such high-powered actors as Pacino, Crowe, and Plummer or is it actually more enjoyable than cutting lesser actors?

PR: There is a lot of pressure the first day. Cutting a scene with movie stars you have never edited, you feel the pressure of maintaining that reputation, but after the first day, it is just another character and a lot of the problems begin to recede.

DR: True, but it is absolutely more fun because they are just better actors, so you are dealing with better raw material. When you are overcoming a problem or trying to get around something, you don’t view it as a performance problem. It’s absolutely more fun and more rewarding. You are just dealing with a better color.

“The movie itself is pretty descriptive and has its own point of view.” – David Rosenbloom

It seems as though the movie is told from two different points-of-view.

DR: Actually, one-third is Russell Crowe’s point of view, a third of it is Al Pacino’s point of view, and a third is when they are together – then, it’s a collective point of view. It’s more in the writing as to whose movie it is, or maybe it’s the interpretation by the audience, but I don’t think anybody’s going to walk away and say that the movie belongs to either one guy. They both have a story to tell, and you can have a great impact on the entire movie just by merely focusing on a scene or replacing it in the structure. It is unique in our work that you can have such an impact.

Your hours must have been totally consuming on this project.

PR: In a typical two-day period, Michael would screen the film, dictate notes, and get those transcribed. Then we would make changes, show the changes to Michael, get more notes, turn the film over to the assistants, and screen it again. We never worked less than twelve hours, and sometimes eighteen hours and anywhere in between, maybe three times a week.

With such an intense amount of work and time on this project, is it worth it in the end?

BG: Absolutely. You work really hard on a Michael Mann movie, but what keeps you going is that Michael makes movies that are about something at a level in which very few directors operate. As an editor you really are subject to the material you are given. With Michael directing – and he is as hardworking or harder working than anybody I have ever seen – you still know, even at the end of an eighteen hour day, that every other editor would jump at the opportunity to work with him in a second.

PR: What we are leaving out is that Michael is constantly inspiring. He is also quite funny.

In addition to Greg King’s sound effects editing, the music and dialogue play a major role in The Insider – as integral to the success of the film as any aspect of post-production. (See article, THE INSIDER’s Sound King)

PR: Yes, and generally you want the sound editors to come on early enough to help you create a great sounding track for the first time you run the movie for the studio, and you cannot always afford that. In our case, the sound editors came on early in post-production.

BG: What I think Greg did beautifully was everything that he created sounded completely authentic and original but also organic to the movie, so you never feel like it’s a sound effect, yet it still impacts the movie in the way you see it and in the way it makes you feel.

PR: Greg’s great strength is his taste and his courage to make decisions about what to leave out; his work is terribly focused and not everyone is willing to do that because it’s risky. The director may ask, “why am I not hearing these sounds?” and then you have to scramble to go and get it, but Greg’s decisions were always right, so he got us down the road quickly.

BG: Also, the dialogue has a very genuine sound, much to Greg Baxter’s credit. He edited the dialogue and is probably as diligent as Michael is about detail.

Music is such a big part of Michael’s movies that we are always putting in temp music and we made an effort not to put a movie score in; it was not what Michael thought was appropriate for the movie, so we were constantly trying to find original instrumental music.

At first, Pieter Bourke and Lisa Gerrard, the co-composers of The Insider, were going to have four or five pieces of music in the movie – some of those were written for the movie and others were pieces that Michael loved and wanted to use. But it ended up that their music worked so well, they did the whole score, save a few pieces of acquired music.

Where does The Insider fall in the pantheon of your editing experiences?

PR: I certainly learned logistically that we were capable of much more than I would have thought possible. Creatively, Michael has very high standards and it’s good to be constantly exposed to high standards. He never allows you to become complacent.

BG: Aesthetically, it’s right at the top. The last two films I worked on, Pleasantville and The Insider, were films that had something important to say and it obviously made me feel proud to be on them. Those opportunities don’t come all the time.