By Patrick Z. McGavin

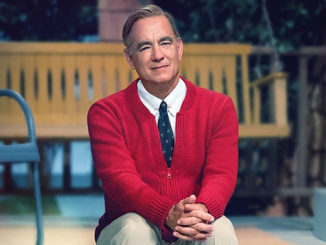

The New York-based picture editor Lucian Johnston specializes in cutting films by directors with a distinctive artistic personality, such as Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of Macbeth” (2021).

“It’s hard to imagine working any other way,” he said. “I’m sure some editors would prefer more autonomy, but there’s a rigor to the work that I find artistically rewarding.”

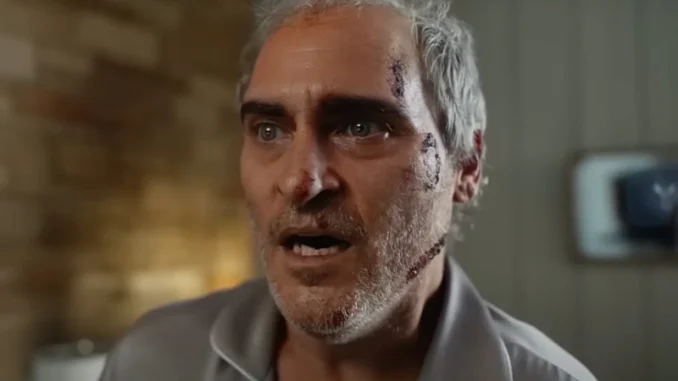

Johnston’s other major collaborator is filmmaker Ari Aster, for whom he has cut all three of his features. Their newest project, “Beau is Afraid,” is a three-hour, psychologically dense Oedipal study of an anxious middle-aged man (Joaquin Phoenix) navigating inner and outer worlds.

CineMontage: This is your third film with the writer and director Ari Aster. How did you meet?

Lucian Johnston: Ari hired Jennifer Lame to edit “Hereditary” (2018). I was Jen’s assistant editor. Ari and I bonded pretty quickly. The first day I met him, he came into the cutting room carrying Joan Didion’s novel, “Play It As It Lays,” and I had literally just finished reading it. That was the weirdest coincidence.

Jen was a mentor, and taught me so much. She was gracious enough to involve me creatively every day on that film. She was pregnant, and eventually left the film early to have her kid. Instead of hiring another editor, Jen and Ari convinced the distributor A24 to let me stay on as the editor. That was really the start of my collaboration with Ari.

CineMontage: How has your creative dynamic evolved working together on the three films?

Lucian Johnston: We’ve established a trust that you can only really have when you spend so much intimate time together. Editing is the most intimate of the different crafts. You’re in a small, dark room with another person all day long, for months and months. That can either make you forge a strong bond, or it can go horribly wrong. I think that’s why so many directors always use the same editor. Once you establish that close rapport, it’s kind of unfathomable to do it with someone else.

With “Beau,” it really felt like we just reached a place of total trust. We work very quickly together and every single edit, every single creative decision, is a conversation that we work through. We talk about different movies and filmmakers every day. I think that’s really important because it’s a way to create a shared language. Taste is so crucial as an editor, because so much of the job is instinctual and curatorial, and talking through references allows you to understand your partner’s taste and sensibilities.

CineMontage: At three hours, “Beau is Afraid” is a work of considerable length. As the editor, what are the particular challenges of having to calibrate and sustain the material?

Lucian Johnston: “Beau” was a much different experience than any other film I’ve ever cut. The film was designed to be an epic, and we always knew it was going to be a three-hour long art film.

That’s much different from how “Midsommar” (2019) was designed. Our first cut of that film was close to four hours. That was terrifying because it had gotten away from us. It wasn’t supposed to be that long. It just ended up that way because of how Ari shot it. We basically had to rewrite the film in post, and restructure the thing so that it actually worked on a storytelling level. It was an incredibly difficult war of attrition, and it took multiple revelatory breakthroughs to get it there.

“Beau” was completely different. Our first cut was a little over three and half hours. Watching that first cut was actually a major relief, because we felt immediately like we weren’t that far off from where we actually needed to be. The foundation of what we had was working for us.

We were able to focus on the fine cutting of every section more. The big picture editing revolved a lot more around pace and cohesion. There are four main sections, and a fifth section, the trial, which functions like a coda. Each section is a different world, and each was shot differently, and thus they were all edited differently. When you have a film comprised of four different worlds, four different styles, four different editing rhythms, new characters entering in each section, how do you properly bring cohesion, connect the segments and give something like that shape and pace? It’s not paced like a superhero film. We have no interest in making it move as fast as possible in every section,

CineMontage: Using the nocturnal urban nightmare of the first section as an example, what were the animating principles of the movement and rhythm?

Lucian Johnston: The first section is the most high octane. Ari shot this segment with pieces that were going to allow us to pace it up. Of course, we did just that. I think it’s really important for the first section to move this way because it does crucial subjective work. Beau is a very passive character, and it’s through the fast-cutting rhythms where we actually gain some interiority. A lot of the character’s anxiety, and the world’s absurdity, come through in the editing patterns. It’s imperative to enter the film like that.

CineMontage: The third episode with the theater troupe is probably the most ambitious because of the various strands you are weaving together, like the animation sequence.

Lucian Johnston: This is where the film really reveals itself as an odyssey. It’s where people seem to accept or reject the film. You either decide to ride the wave or you don’t. But once again, the film shape shifts here. As far as editing, we are now in a completely new rhythm.

The animation sequence was the very first thing Ari and I cut. We had to do that so that we could turn it over to our animators immediately, because it was so labor intensive. The entire segment was shot practically on a soundstage. In cutting the shots together, we used the angel’s voiceover to structure the sequence. Even though the shots are very carefully designed to piece together, it was actually a big challenge to initially editing. Even with the narration serving as a structural device, you still feel like you’re flying blind.

Everything was done on a green screen. When you don’t have any of the interactive elements to help guide you—really understanding how to propel the thing editorially almost feels impossible. We needed the animation itself to also help inform more of the picture edit. We just pieced it together as best we could, and then turned it over to our animators, Joaquin Cocina and Cristobal Leon.

After that we didn’t touch it for months. We did have animation meetings every single week. We’d meet them, and see what they had done, and give them notes. We had to let it slowly take shape before we could start actually picture editing it again. We changed some of the cut points and the angel narration timing based on how the animation started coming together. This is my favorite section in the film.

CineMontage: Did you struggle with how you wanted to incorporate the flashbacks into the larger narrative, or does it conform pretty closely with the script?

Lucian Johnston: There are three flashbacks that serve as the connective tissue between the four distinct sections. The first and the third conform closely with the script. The second flashback was entirely created in post. We included that to give all of the transitions a symmetry, and to strengthen the narrative thread of the brother being locked in the attic, which some people seemed to be struggling with.

Our first assistant editor Max Berger really helped us figure that one out. The third flashback plays as scripted, but a lot of care went into getting the VFX right. It’s actually one of the most complicated VFX shots in the film, and it took forever to nail, especially the pull back at the end. So much detailed work went into shaping those transitions. They are so important because they really organize the film, and are a key factor in bringing some cohesion to the entire thing.

CineMontage: Was getting the tone right the complex part of the creative equation?

Lucian Johnston: I feel like I could write a dissertation about this. This is a great place to talk about the other artistic contributors. Ari and I had never used a music editor before. I was frankly skeptical about their importance before this film. Katherine Miller came on to help us, and I can’t overstate how massively crucial her work was on the film, especially regarding tone.

The score was always going to be one of the tonal aspects that was going to have to glue everything together. Katherine worked tirelessly to create a temp score that did just that. The nuanced accent work, the thematic motifs, the emotional color of everything—she really laid the groundwork. Bobby Krilc, our composer, came in, and they worked closely together to shape the final product. It’s by far the most complicated score I’ve ever witnessed, and it’s doing so much important tonal work that ties together all of the sections.

CineMontage: Did you go to film school, or study formally?

Lucian Johnston: No, I went to Sarah Lawrence, and did the liberal arts thing, studying a bit of everything. I originally wanted to be a writer. I studied film a bit and made some films, but I actually taught myself how to edit when I was a teenager, making skate videos. Everything else, I learned on the job as I worked my way up through the assistant editor ranks.

CineMontage: Is there something intrinsic to editing that speaks to you in a way separately from cinematography, sound or even writing and directing?

Lucian Johnston: It is so comprehensive. I was first drawn to film editing because of how similar it felt to writing. It’s the part of the process where you give language to cinema. You use the vocabulary, grammar, and syntax of the medium to give it form. You need to be a cinematographer, and understand composition. You are constantly reframing shots, and you need to understand the pictorial elements, in order to properly juxtapose shots.

You get to direct as well. You need to understand performance, and how to track a performance, on the most microscopic level. You also are involved, creatively, in every phase of the process, from the very beginning, to the very end, which is not the case for any other film craft. Basically, it’s the most filmmaking part of filmmaking.

Patrick Z. McGavin is a cultural journalist and writer in Chicago. He publishes the film website Shadows and Dreams (www.patrickzmcgavin.substack.com).