by Kevin Lewis

The summer season is always saturated with sequels in Hollywood, and this year is no exception. But it was the film serials, from the early days of cinema, that were the true forerunners of contemporary franchise pictures and tent-pole releases. In fact, you could even say that serials were the prequels to today’s sequels.

The serials — and the subsequent, approximately one-hour-long films called “series” — produced by Hollywood studios from the 1930s to the late 1950s epitomized the terms “programmers” and “product.” In the days when an evening (or day) at the movies was a full three- to four-hour program, these films were the bottom half of the bill. The A picture with stars was the top half, while the shorter series film was the B movie, preceded by a newsreel, an animation short, a travelogue or a 15-minute chapter in a serial. The serial was the real “product,” not unlike processed meat. If Hollywood was a “sausage factory,” as it has frequently been described by detractors, then the serial was the reliable Spam.

Serials came in all forms and mimicked almost every genre, except one: the romantic melodrama, or the traditional “women’s picture.” That was a staple of radio — the daytime serial, the soap opera — and went directly from radio to television. However, there were early film serials with canine stars, such as Rin Tin Tin and Rex, the Wonder Horse. There were jungle serials using Tarzan and variant reincarnations of him. The mad scientist out to control the world was a very popular subject, as were science-fiction films, featuring Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers, and comic book crime fighters like Superman and Batman.

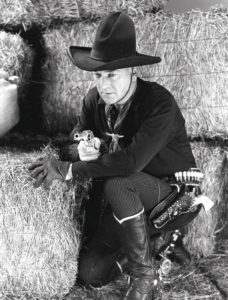

Universal Pictures/Photofest

Each serial chapter ended with a cliffhanger. Though the A film got the royal treatment, it was the next chapter of the bottom-billed serial that brought return business. The kids in the family made sure that Mom and Pop got them to the next installment. When kids saw the serial at the kiddie matinee, it was a Saturday afternoon they dreamed of all week before. And they went armed with the toys, decoder rings, cap pistols, etc. that they bought and which were featured as props in the films — the beginning of movie licensing and merchandising.

The most fondly remembered serial era was from the 1930s to the television age, but the silent era was perhaps the most interesting for its perspective on feminism and the creation of the Western myth with real cowboys. The transition from theatrical realism into the motion picture narrative can be traced clearly during this era.

Photofest

The serialization format was originally devised by the publishing industry. Many 19th-century novelists, especially Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo, developed their stories over months or a year as serialized novels, published and sold in separate, numbered parts.

This open-ended form enabled filmmakers to commence a mystery or action story for a 10-minute (one-reel) time limit and guarantee an intrigued audience to return for the succeeding parts. In addition, it gave cash-strapped filmmakers more time to find investors to complete a film. As a precursor of today’s focus groups, serials also afforded filmmakers the opportunity to determine how the story would develop by following how audiences responded to individual characters.

The chapter serial was one of the earliest narrative genres when films were just one or two reels long in the first decade of the 20th century. A century ago, the embryonic lot of film producers and exhibitors — who were oftentimes the same entity — were forced to plagiarize literature, theatrical hits, the tabloid press and even each other’s films to get product on the screen every day and night. The motley urban masses teeming into the newly industrialized cities demanded constantly changing entertainment.

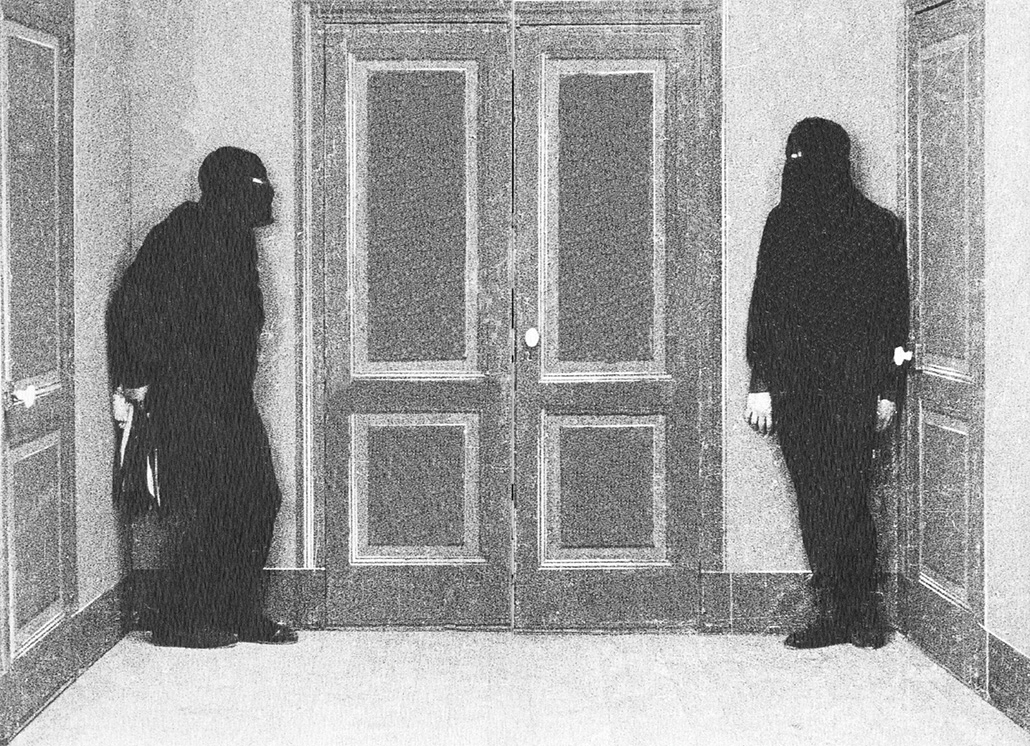

Columbia Pictures/Photofest

The earliest known serial was France’s Nick Carter (1908), derived from the best-selling detective series. Thomas Edison created what is considered to be the first American serial, What Happened to Mary (1912).

Oddly enough, the silent American serials focused on women in distress. Women in that Suffragette era were the plucky stars who escaped from one near-death experience to another. They drove cars at breakneck speed and even flew airplanes. Pearl White in The Exploits of Elaine (1913) and The Perils of Pauline (1914-15) became world famous and one of the earliest superstars. Her studio, Pathé, produced 55 series between 1914 and 1929, many featuring women as action heroines. She was followed by the likes of Grace Cunard, Ruth Roland, Helen Holmes and Helen Gibson. Holmes and Gibson successively played the title character in The Hazards of Helen (1914-16), which became the longest theatrical serial, eventually totaling 116 episodes and running almost 24 hours. Audiences loved seeing women threatened with death from falling bridges, plummeting autos, whirling buzz saws and oncoming trains, but escaping by their wits and strength.

But it was the popular theatre, not the movies, which invented the cliffhanger. The most famous threats — the villain tying the bound and gagged victim to a railroad track just when a train was coming ‘round the bend, or the villain tying the victim to a sawmill table with a whirling buzz saw approaching — were derived respectively from two barnstorming theatrical hits that toured for decades: Under the Gaslight (1867) and Blue Jeans (1888). In both of those shows, it was the woman who saved the man from certain death by overpowering the villain. Curiously, the movies made the woman the victim. Two fine books published in the 1960s by Kalton Lahue, Continued Next Week and Bound and Gagged, explore the silent serial and its women.

Many of the aforementioned serials and series films would go on to be resurrected, repackaged and renamed for the soon-to-be-burgeoning television medium, not to mention later being reincarnated, reimagined and repurposed by the feature film industry itself in the early 1960s.

In France, the serials of Louis Feulliade were sensationally popular and they have been rediscovered by film historians and critics as the inspiration for Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock, Alain Resnais and possibly Luis Buñuel. Feulliade’s Fantomas (1913) was released 100 years ago this summer and was an adaptation of a published French serial about a master criminal who heads a gang of murderous thieves but who also is a respected man above reproach. His other serials throughout the decade were variations on this theme, revealing the corruption among the bourgeoisie. Murders and kidnappings are executed in mundane settings in broad daylight. The thrill and suspense emotions among viewers was increased because Feulliade never prepared them for the crimes; audiences just anticipated more mayhem because they knew anything could happen after the first few murders. His most famous serial, Les Vampires (1915-16), made a star of Musidora as the notorious female criminal Irma Vep.

By the 1920s, the age of emancipation, these women and their ilk were gone from the screen, although two women later emerged as serial queens during World War II: Linda Stirling in Zorro’s Black Whip (1944) and Joan Woodbury in Brenda Starr (1945). The cowboy became the star of the serial, as well as the one-hour-long series film with a continuing character in the ‘20s. Harry Carey, Tom Mix, Buck Jones, Rex Lease and Hoot Gibson were the most popular stars. Joseph P. Kennedy got a foothold in the film industry by signing cowboy movie star Fred Thomson for short films produced by Film Booking Offices.

Perhaps the biggest box office draw of the mid-1920s was the German Shepherd Rin Tin Tin. The dog established both future mogul Darryl F. Zanuck, who wrote many of the scripts, and Warner Bros. The studio featured the dog in both serials and features between 1923 and 1931, until his heart gave out at 16 years old in 1932. Then Rin Tin Tin, Jr. starred in other serials and features until the mid-1930s. They were the gravy train for Warners.

According to a Hollywood legend, which was discussed in Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, the 2012 Susan Orlean biography of the canine star and his successors, Rin Tin Tin had more votes than his human colleagues for the very first Best Actor Academy Award. Even the Academy was abashed and gave the Oscar to Emil Jannings (for The Way of All Flesh, 1927; and The Last Command, 1928). When Jannings went back to Germany to become a state artist for the Third Reich, Rin Tin Tin didn’t look like such a bad choice in hindsight.

The talkie revolution thinned out the herd of smaller studios unable to afford the equipment and studio space, and by the early 1930s, only four studios were producing serials: Universal, Columbia, Republic and Mascot. Mascot was absorbed by Republic in 1935. Before that, its most memorable serial was The Three Musketeers (1933) starring John Wayne.

Mascot and Republic starred Wayne in a succession of roughly one-hour, low-budget Western series films until John Ford rescued him for Stagecoach (1939). Gene Autry played essentially the same cowboy in another lengthy series of singing cowboy films at Republic from 1934 to 1942. He also starred in the 13-chapter serial Phantom Empire (1935) from Mascot. Autry and Wayne were the only Republic actors to be listed among the top 10 box office stars. When the former enlisted in the Army Air Forces in 1942, Roy Rogers took his place as Republic’s King of the Cowboys in a long series of Westerns, also starring his wife Dale Evans. Autry became big box office again for Columbia in a series of Westerns from 1949 to 1953.

Republic produced 66 serials from 1936 until it shuttered in 1955, the most notable being the four Dick Tracy serials (1937-41), Adventures of Captain Marvel (1941) and two The Lone Ranger serials (1938-39). And the studio has the distinction of providing Leonard Nimoy, the future Mr. Spock, his first shot into outer space with the serial Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952).

Columbia had the longest tradition of cowboy series ranging over 300 B Westerns between 1930 and 1958. Among its Western stars with their own series were Charles Starrett (who played the Durango Kid), Buck Jones, Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Tex Ritter and George Montgomery. Randolph Scott was an A star in feature Westerns who was among the top 10 box office stars from 1950 to 1953.

The most famous cowboy star, William Boyd, was not associated with a major studio. The former Cecil B. DeMille actor was a fading star when independent producer Harry Sherman cast him in the first Hopalong Cassidy film in 1935, distributed by United Artists. Sherman produced 54 second-feature Hopalong Cassidy films until 1943, when Boyd bought the series from Sherman and produced the final 12 under his Hopalong Cassidy Productions banner until 1948. Boyd would become a multi-millionaire when he later licensed the films for early television.

Among Columbia’s 57 serials produced from 1937 to 1956 are such classics as Flying G-Men (1939), Mandrake the Magician(1939), The Shadow (1940), Terry and the Pirates (1940), Batman (1943), Superman (1948), Batman and Robin (1949) and Captain Video (1951).

Columbia and Universal also produced many series of hour-long, low-budget comedies, which would soon ease their transition into television.

Some of the Columbia series were very long lasting. Blondie, based on the comic strip, was a film series from 1938 until 1950 with 28 productions. Boston Blackie, a detective series, had 14 productions between 1941 and 1948. Jungle Jim, with Johnny Weissmuller, had 16 productions from 1948 to 1955. The Lone Wolf lasted from 1926 to 1949 with 19 films. The Adventures of Rusty, a German Shepherd, birthed an eight-film litter between 1945 and 1949. The Ellery Queen series had seven films from 1940 to 1943, Crime Doctor starred Oscar-winning actor Warner Baxter in 10 films between 1943 and 1947.

Universal holds the record for the production of serials. During the period of 1914-1946, approximately 137 serials were made. Among the most remembered are Flash Gordon (1936), which made a star of Larry “Buster” Crabbe; Buck Rogers (1939); The Green Hornet (1940); Don Winslow of the Navy (1942); Junior G-Men (1940-42); and The Adventures of Smilin’ Jack (1943).

The studio’s most popular series were probably the Sherlock Holmes series with Basil Rathbone, which started at 20th Century-Fox in 1939, although 12 of the series were produced at Universal from 1942 to 1946. The Ma and Pa Kettle series had 10 films produced between 1947 and 1957. Francis, the Talking Mule, starring Donald O’Connor as the human half of the team, yielded seven films between 1950 and 1956.

MGM and Fox had limited participation in the production of series. The former produced the Maisie series starring Ann Sothern with nine films from 1939 to 1947, the Andy Hardy series starring Mickey Rooney with 16 films from 1936 to 1946 (as well as a reunion film in 1958) and seven Lassie films released between 1943 and 1951. Fox produced eight Mr. Moto films starring Peter Lorre between 1937 and 1939, the Charlie Chan films with 41 films from 1929 to 1949 (with Monogram Pictures taking over from 1944 to 1949). In addition, the Philo Vance series — with 14 films among them — was successively produced by Paramount, Warner Bros. and Producers Releasing Corporation between 1929 and 1947.

Many of the aforementioned serials and series films would go on to be resurrected, repackaged and renamed for the soon-to-be-burgeoning television medium, not to mention later being reincarnated, reimagined and repurposed by the feature film industry itself in the early 1960s.

This being an article on the early film serials and series, which were precursors to the sequels of the modern era, it is only fitting that we leave you readers hanging here until next issue, when part two of this essay will conclude our look at how these original staples of the movies morphed into episodic TV programs and feature film franchises that continue to this day, and how much those contemporary counterparts were influenced by their antecedents.