by Kevin Lewis

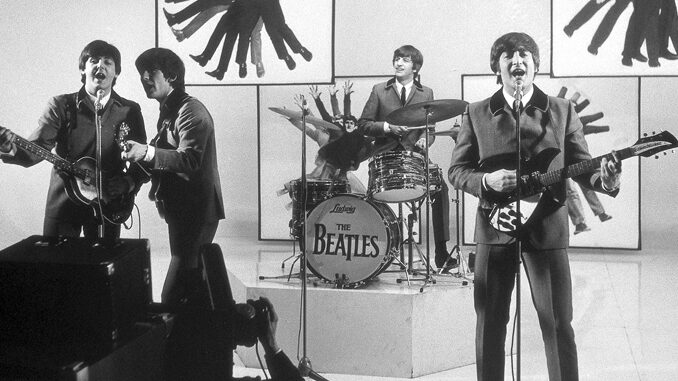

It is hard to believe now, but in the early 1960s, the young, long-haired Liverpudlian lads John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr (known collectively as the Beatles) were considered to be an insidious force, challenging British as well as American stereotypes of youthful masculinity, just as their distinctive, infectious “beat music” threatened to take over the pop charts of both countries. In short order, the band succeeded decisively; thanks to the Fab Four, as they were dubbed, popular music underwent a massive sea change and boys’ hair and fashion were never the same again. And the girls screamed and squealed in delight over both.

When their first film, A Hard Day’s Night, premiered in July 1964 in the UK (and a month later in the US), Village Voice film critic Andrew Sarris called it “the Citizen Kane of jukebox musicals.” It proved a game changer — not only for the increasing popularity of the musical group (if American kids weren’t already Beatles fans, they certainly were after seeing the film), but for musicals and music-based films, which were never the same again. In fact, almost every genre of film — from spy thrillers to caper comedies — was influenced by the innovative editing, including jump cuts, zooms in and out, and handheld, cinema vérité-style cinematography, all of which were inspired by the contemporary Nouvelle Vague movement in French cinema.

Not much was expected of the film, in which the Beatles play themselves, because it was only created to cash in on Beatlemania, which had already swept Britain and was surging in the States, especially after the group’s historic debut performance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. In fact, production began only a month later. Producer Walter Shenson had a distribution arrangement with United Artists Pictures for the low-budget ($500,000) black-and-white film, as well as its much-anticipated soundtrack album.

If American kids weren’t already Beatles fans, they certainly were after seeing the film.

Because expectations were low, American expatriate director Richard Lester, who had been working in British television for a decade, had the freedom to be daring and experimental with A Hard Day’s Night. He had directed one prior music- related film, It’s Trad, Dad (aka Ring-a-Ding Rhythm! in the US, 1962), which featured, among other acts, American rock ‘n’ roller Gene Vincent, a favorite of the Beatles. Lester would also helm the band’s second feature, Help! (1965).

The film’s production team came from British television as well. The picture editor was John Jympson, who, like Lester, began as a runner at London’s Ealing Studios, but soon graduated to the editorial department. Jympson would go on to edit such English and American films as A Fish Called Wanda (1988) and the remake of Little Shop of Horrors (1986) before his death in 2003. The screenwriter, Alun Owen, was a British television writer and, with the exception of the features A Hard Day’s Night and Joseph Losey’s Concrete Jungle (1960), remained as such.

Many members of the supporting cast were also from British television, including Norman Rossington, who played the chronically chagrined band manager. Rossington divided his time between TV and films such as Lawrence of Arabia (1962), in which he had an uncredited part, and several of the Carry On… comedies of the late 1950s and early ’60s. Wilfred Brambell, who stole A Hard Day’s Night as Paul’s troublemaking grandfather, was the star of the hit Britcom Steptoe and Son (1962-65, 1970-74), which would be adapted to become the American classic sitcom Sanford and Son (1972-77).

For their part, the Beatles were great fans of The Goon Show, a radio program airing on the BBC Home Service from 1951 to 1960 starring Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and Spike Milligan, as well as several Goons features and TV shows from the mid-’50s, some of which were helmed by Lester. They wanted Lester to direct them because of that connection, as well as his co-direction (with Sellers) of The Running, Jumping & Standing Still Film (1960), which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Short Film – Live Action. In fact, the “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence in A Hard Day’s Night, in which the band members run and jump around in a field, complete with creative camera work, was a nod to the Goons and the Lester/Sellers short.

In addition, Mack Sennett’s “Keystone Kops” are evoked when the Beatles are being chased by bobbies after springing Ringo from jail. Lester and Owen used these prior, slapstick influences in the shaping of the Beatles as an offbeat comedy group rather than just as musicians in the film. They also made Ringo an endearing comic character by emphasizing his social gaucherie and shyness around women because of his prominent nose.

Ringo even recalls Charlie Chaplin or Harpo Marx in the comic scene where he gallantly throws his overcoat over puddles to guide a woman through the muddy streets, until the final puddle turns out to be a large hole, into which the unsuspecting woman disappears. Starr is also credited with giving the film its unique title, when the drummer delivered one of his infamous malapropisms while describing what a tough, long day it had been. Everyone loved it and it stuck. Then Lennon and McCartney had to write the title song before production wrapped!

Lester cleverly places the Beatles’ songs in the storyline, and the “If I Fell” segment advances the story in a self-reflective way. The Beatles are on the journey to perform on a variety show, not unlike The Ed Sullivan Show. When they have to imprison the rebellious granddad in the train’s pet kennel to keep an eye on him, they rehearse “If I Fell” in the kennel, only to be watched like caged pet animals themselves by the giggling schoolgirls (one of whom, Pattie Boyd, would become Mrs. George Harrison).

The youthful revolution against the “Dad’s Army” World War II generation that arose in the early 1960s is declared immediately in the film with the introduction of Paul’s grandfather, who is a reluctant appendage to the lads. “He’s very clean,” Paul tells his comrades, a clever upturn on the “dirty old man” description of Brambell’s character in Steptoe. The train trip which opens the film juxtaposes several layers of British society: the adoring schoolgirls who pursue the Beatles, the working-class managers of the band, and a sneering, pompous traveling businessman who forces his traveling habits on the boys. “I fought the war for your sort,” he snorts, to which John retorts, “Give us a kiss,” and Ringo adds, “I bet you’re sorry you won.”

A Hard Day’s Night received Oscar nominations for Owen’s original screenplay and the adapted score by George Martin, the Beatles’ record producer. The film’s songs also received a Grammy nomination for Best Original Score. It is difficult to determine how much Lester collaborated with editor Jympson because the jump-cutting was emblematic of the director’s work at that time. Lester often stated that he preferred editing to directing, and Jympson mainly edited big studio films such as Zulu (1964) during that period. In any case, it was a jewel in the British cinema crown for both of them.