By Peter Tonguette

For 18 years, on and off, the director of “Five Easy Pieces” (1970) and “The King of Marvin Gardens” (1972), and, as part of the legendary BBS Productions, a producer of “Easy Rider” (1969) and “The Last Picture Show” (1971), was a fixture in my email inbox.

Bob Rafelson, who died on July 23 at the age of 89, first came into my life in the summer of 2004, when I, then an enterprising young film critic, approached him with an interview request. After some back-and-forth—good-natured jousting, I would learn, was a Rafelson trademark—we agreed to a two-part, multi-hour phone interview in October 2004. The conversation encompassed Bob’s entire career and gave him a platform to air his many idiosyncratic opinions and theories about movies and how to make them. In January 2005, the interview was published in a small online film magazine.

In the years that followed, Bob and I spoke by phone only a handful of additional times—and we did just two additional on-the-record phone interviews—but, to my surprise, he remained a regular, you might say even persistent, email correspondent.

You can seldom get a read on people through electronic communications, but being on the receiving end of Bob’s emails over nearly two decades gave me, I think, as true a measure of the man as anyone. Bob was combative—he would toss out provocative comments and expect you to volley back—and even rather demanding. The one constant in our exchanges—perhaps the one thing that kept him writing to me for so long—was his periodic request for me to send, re-send, and send again a link to our interview.

I took this as flattering. Although my skills as an interviewer were not well honed at 21—my age when I interviewed Bob in 2004—I had genuine enthusiasm for his work that must have come through to him. After all, I had sought him out not because he was such a big-name director by this point—his most recent film, a modest but efficient crime movie starring Samuel L. Jackson, “No Good Deed,” had come and gone the year before—but because, I was thoroughly persuaded, he was a great director.

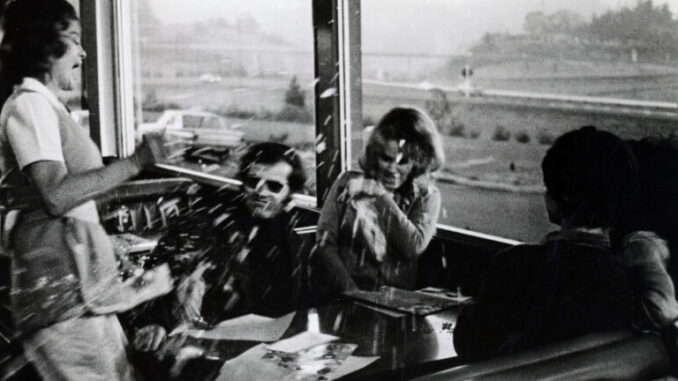

I loved the spit and vinegar of “Five Easy Pieces”—the way that Bobby Dupea (Jack Nicholson, his frequent collaborator and devoted pal) reams out the waitress from whom he is attempting to order a chicken salad sandwich sans chicken, or the way Bobby dresses down the upper-class egoist who speaks condescendingly of his girlfriend, Rayette (Karen Black). I loved, too, the invigorating, unrelenting bleakness of Bob’s vision, which, I felt, made him particularly well-suited for his genre of choice in later years: the film noir, his contributions to which included his brilliant remake of “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1981) and “Blood and Wine” (1996), both also starring Nicholson.

Shown from left: Lorna Thayer, Jack Nicholson, Karen Black; (back to camera from left) Toni Basil, Helena Kallianiotes. PHOTO: Columbia Pictures.

Not that Bob would nod and agree with any of this. Our first major disagreements came early, when, prior to our interview, I made the mistake of emphasizing his supposed interest in film noir. “I can’t put them in a genre,” Bob wrote back. “And if I did, I don’t much care for the genre. ‘Noir.’” Somehow, I rehabilitated myself sufficiently to induce Bob to proceed with the interview, but I had a taste of his restless, irascible nature.

Bob and I got through the interview process—which included, after we spoke, my sending him the transcript multiple times, including by mail to his home in Aspen, Co.—and, amazingly, he was pleased with the results. If anything, he encouraged me to press him more, since he (correctly) discerned that my interview style consisted of letting the auteur ruminate, as he put it to me. Near the very end, Bob decided that our interview needed some “comedic relief,” so he made up a few new “questions” and “answers.” “Use your own words for Tonguette questions,” he advised me in typically jocular fashion. “Revise (with wit) mine.”

Bob liked a give-and-take, and when he wasn’t asking me for a link to our interview, he was doling out other assignments. At one point, Bob tasked me with making sure that the little-seen “No Good Deed” was included in the various movie-review compendiums that were then still being published annually, including Leonard Maltin’s. A few years later, Bob asked me to help get his producing credits on IMDB updated, and a few years after that, he was after me to correct his Wikipedia entry—a project that continued intermittently up to last year and, I’m sure, would still be ongoing if Bob was here.

Bob’s personality was too forceful to refuse. One could see, through his sharply worded entreaties, how he had made himself the leader of the New Hollywood movement. Underneath, though, was a man of generosity, compassion, and feeling. As his films trickled onto DVD and Blu-ray, Bob always saw to it that I was sent copies; when I asked him for interviews, he usually relented, even if they were just by email. When I wrote obituaries of his BBS partner Bert Schneider and his “Five Easy Pieces” leading lady Susan Anspach for Sight & Sound magazine, I needed comments from Bob, and he complied—brilliantly—both times.

In January, when Peter Bogdanovich died, I could tell Bob was shocked; this was the loss of perhaps his greatest protégé, and someone who was, at 82, younger than he was. Bob and I exchanged many emails about Peter, and this spring, I asked Bob to sign my original one-sheet poster for his wonderful—atypically warm-hearted—1976 comedy-drama “Stay Hungry,” starring Jeff Bridges, Sally Field, and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Bob played along with this unusually (for me) fannish request, and sent me back the poster with a wonderful inscription that referred back to the title of our long-ago interview. He really liked that interview! Without ever saying it aloud, I sensed this was a concluding gesture to our friendship. Maybe we both realized, after the loss of Peter, that life was short.

He willingly he doled out credit to others, including film editors. He called them, in typically grandiose fashion, “the priests of film.”

I last heard from Bob just two weeks before he died. I emailed him to say that James Caan—with whom Bob had worked on a terrific made-for-television adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s “Poodle Springs” (1998)—had died. I asked Bob what Caan had been like to work with, and Bob replied with his shortest-ever email: “Amazing.”

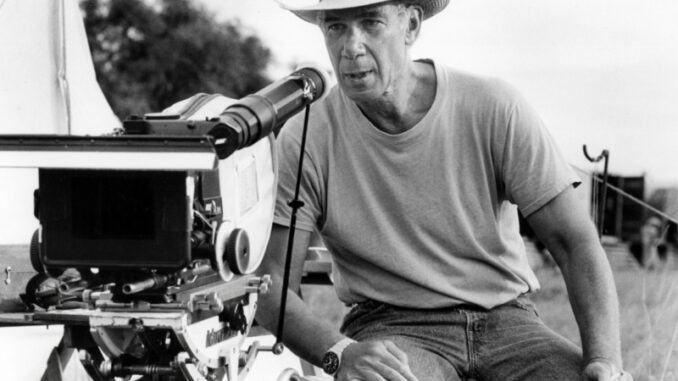

Bob was a huge personality, but when I look back at our conversations, I find how willingly he doled out credit to others, including film editors. He called them, in typically grandiose fashion, “the priests of film.” For his 1968 debut film “Head”—an ungainly, unhinged movie starring the Monkees, the TV sitcom band he had helped create—Bob favored wildly experimental, Stan Brakhage-like editing. Edited by Mike Pozen, ACE, the film uses sometimes imperceptibly quick cutting and abrupt scene transitions to get across its uniquely psychedelic vibe. Having exhausted that freewheeling style, Bob then shifted to a rigorous, highly restrained approach to editing in subsequent films; the takes were long, the cuts were well spaced.

“By the time I came down to shooting ‘Five Easy Pieces’ and ‘The King of Marvin Gardens,’ after having somewhat exploited the two-frame cut in ‘Head,’ I wanted a static camera, a more naturalistic kind of movie, obviously, than ‘Head,’ and everything was somewhat prefigured in my head,” Bob told me in 2004. “In fact—I don’t recall the exact amount—but there were very, very few cuts in ‘The King of Marvin Gardens.’”

Bob emphasized to me that what he called “cutting in the camera”—shooting as little film as you could get away with—was partly a function of the low-budget productions he oversaw at BBS. “Remember,” he told me, “I was a producer of Bogdanovich’s ‘The Last Picture Show,’ so I saw his minimalistic dailies. So I don’t want to sound dogmatic about the way I cut in the camera, it’s just it was an inexpensive way and a knowing way, an experienced way, of trying to reduce the costs of making a movie.”

Bob worked with many great editors, including Christopher Holmes and Gerald Shepard on “Five Easy Pieces,” John F. Link II on “Marvin Gardens,” Graeme Clifford on “Postman,” and Thom Noble, ACE, on “Mountains of the Moon” (1990). I know that he especially enjoyed collaborating with Steven Cohen, ACE, on “Blood and Wine” and “Poodle Springs.” “Editors don’t care in the end what your intention was; they may have to create your intention or, if it’s not on the film, dispense with it,” Bob told me. “And sometimes there are extraordinary battles: giving up things or discovering things they figured out you had little if anything to do with.”

After Bob died, I emailed one of my favorite interviewees, Oscar-winning picture editor John Bloom. Now retired, John cut Bob’s 1987 film noir “Black Widow,” a striking all-female thriller starring Debra Winger as a Justice Department official and Theresa Russell as the husband-offing serial killer in her sights. John remembered Bob much as I did.

“Bob was a formidable presence and, in a way, quite intimidating,” Bloom told me. “My clearest memory was when Bob said, somewhat pompously it must be said, that he may only be an average director but his editing ability was truly exceptional, and that he could see an edited sequence and discern if there was a difference of a single frame, a rather extraordinary statement in view of the fact that a single frame of film represents a mere 1/24th of a second.”

Nonetheless, Bob hired John, and as John describes it, they formed a tight bond in the cutting room. “He could be intimidating, somewhat daunting, rather grand and great fun and I adored our time together,” said Bloom. One time, Bob asked John for several shots in a sequence to be extended, and John, who felt the additions were unnecessary, made no changes “but added a few splices which seemed to indicate that alternations had actually been made.”

“He had a look at what I had done (or not done), announced that the sequence was much improved, disappeared back to his office whilst I had a quiet chuckle to myself and was able to reflect on the man who had told me on interview that he could tell if a sequence had been altered by a single frame,” Bloom said. “I did confess all this to Bob later, when we had become very close, and he roared with laughter at the deception.”

John—who believes that a rare Rafelson casting misjudgment mars “Black Widow’s” second half—reflects on the experience fondly. “I think the first part of the movie is masterful and something of which I am immensely proud, and I will always look back on my time spent with Bob Rafelson with great affection,” Bloom said.

As for me, when I think back on Bob Rafelson’s extraordinary career—and the fact that we maintained an unlikely, nearly two-decade dialogue—I can only repeat the last words Bob typed me: “Amazing.”