by Kevin Lewis

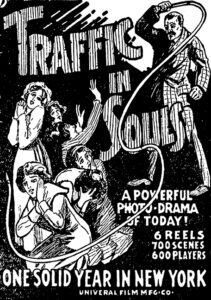

The early silent film Traffic in Souls (1913) remains just as timely as when it was released 100 years ago. The sex slave trade today operates with the same methodology as depicted in this exposé of forced prostitution based on the Rockefeller White Slavery Report of 1910. When the film was placed in the National Film Registry in 2006, the Library of Congress announced that it “presaged the Hollywood narrative film,” and restored the film to its rightful place in film history. Though it was the first blockbuster American movie, and expanded the attention span of audiences used to 15- or 30-minute films to roughly a 90-minute running time, this important film was overlooked for many decades by film historians, who regarded it as an exploitation film rather than a serious narrative like those directed by D.W. Griffith.

Traffic in Souls established the American feature film, surpassing in story construction the stagey Italian and French spectacles shown in America in 1912. It sidestepped censorship efforts by claiming that it was a true story filmed to enlighten the public. In fact, the film could be an episode of today’s Law and Order: SVU. Law and Order is still using the conceit of Traffic in Souls: The criminal mastermind turns out to be a person of wealth, power or official status.

The film’s creator, George Loane Tucker, who is even more ignored than his work in film histories, was actually a seminal figure in the development of the motion picture industry. Perhaps because he was formerly a railway clerk, whose job was to protect gold and mail deliveries from mail thieves, he was attracted to stories about con artists. He entered the film industry as an actor with Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Picture (IMP) Company in 1909, began writing scenarios soon after, and became a director, mainly of shorts. He played the wireless operator in Traffic in Souls.

Besides this film, he co-wrote and directed two films later in his career that had great influence in the careers of two giants. In 1918, Tucker directed Virtuous Wives, the fledgling production of a pioneer theatre chain owner, Louis B. Mayer. The success of the movie made Mayer a player in the industry, attracting the attention of Marcus Loew of the Loew’s Theatres chain, who made Mayer head of production of what would become Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios in 1924.

In 1919, Tucker directed another exposé, this one on fake faith healers: The Miracle Man, which made a major star of Lon Chaney and made a fortune for Paramount Pictures. Two years later, Tucker was dead at the age of 49, just when the film industry was entering its Golden Age. His memory was buried by the moguls he helped create.

Like Tucker, Jack Cohn, the uncredited editor and producer of Traffic in Souls, has been ignored by film historians, and even in his lifetime was eclipsed by his brother Harry. The fullest account of his early years in New York can be found in the biography of Harry, King Cohn by Bob Thomas. “Jack was stocky, pugnacious, accustomed to the language of the street,” writes Thomas. He left his job at an advertising agency, and the study of law at New York University, to work in the laboratory of IMP in 1908. The movies fascinated him, and he moved rapidly from department to department. He was a genius as a picture editor. In those nickelodeon days, one-reel films were the normal length. As an editor, Cohn “discussed scenarios with directors and suggested expanded scenes,” according to Thomas. Cohn repeated shots, wrote expository inter-titles and juxtaposed action. “By judicious cutting, he could provide a finished product that would be double the length the directors originally intended. Thus, Laemmle got two reels for the price of one,” explained Thomas.

In 1912, IMP joined with several other film studios from New York and New Jersey to release their product through one distribution source, Universal Film Manufacturing Company. Cohn had developed the newsreel, based on the model of Pathé in France, first at IMP and then at Universal. He used his skills for montage to produce a regular newsreel, Universal Animated Weekly. At this time also, Universal was in turmoil because of the constant fighting and suspicion of the partners, which led to the union of Cohn and Tucker.

It was Tucker who devised the idea for Traffic in Souls, with a scenario by Walter McNamara, based on both the Rockefeller Report and the success on Broadway of plays on white slavery, most notably The Lure (1913), produced by the Shubert brothers. Cohn was already a master at editing documentary footage, so he was comfortable working with scenes shot on the streets, and seamlessly inter-cut stock footage of Ellis Island and New York scenes.

Accounts differ about the production, but Laemmle could not justify a $5,000 budget to a Universal board of directors for an original multiple-reel exploitation scenario. Tucker, Cohn and IMP star King Baggot guaranteed the production cost. IMP had already made inroads in feature films with a handsome production of Ivanhoe, filmed in Wales in 1913.

But feature films of that period — especially those produced by Adolph Zukor — were photographed versions of stage successes with theatrical stars and shown in legitimate theatres. Early film exhibitors had to use legitimate theatres to show special films because other than nickelodeons, there were very few venues at the time built for film exhibition. Universal’s success with the documentary Paul J. Rainey’s African Hunt (1912), released in Shubert theatres through the Shubert Feature Film Booking Company, may have led Laemmle to approach the Shuberts for financial support and booking guarantees.

According to Thomas’ King Cohn, Tucker and Cohn probably shot the interiors for Traffic in Souls at the IMP studio on Eleventh Avenue and 53rd Street in Manhattan, when the regular IMP studio manager was in Europe. Many of the scenes were also shot on the streets of New York and Brooklyn. Eventually, Traffic in Souls was 10 reels long, which Cohn cut down to six.

As Laemmle expected, the board of directors were shocked that a film could cost $5,700. Laemmle offered to buy the film for $10,000, which convinced the board to release it through Universal. The Shuberts bought one-third interest in the film for $33,000, and it opened at Joe Weber’s Theatre (aka Weber and Fields Imperial Music Hall) on Broadway on November 24, 1913. In what may be a first in Hollywood bloated ballyhoo, the original trade advertisement proclaimed:

Traffic in Souls — The sensational motion picture dramatization based on the Rockefeller White Slavery Report and on the investigation of the Vice Trust by District Attorney Whitman — A $200,000 spectacle in 700 scenes with 600 players, showing the traps cunningly laid for young girls by vice agents — Don’t miss the most thrilling scene ever staged, the smashing of the Vice Trust.

An estimated 30,000 customers paying 25 cents packed the first theatre playing the film, and approximately 28 New York theaters wound up showing it. Eventually, the film grossed over $450,000; Laemmle bought out his partners and Universal Pictures began its fabulous history.

In his 2001 book Celluloid Skyline: New York and the Movies, James Sanders writes about Traffic in Souls: “Location shooting would give its sensationalized account a sense of immediacy and veracity; the ability to cross-cut among several stories from different parts of the city would allow it to dramatize the diverse nature of the problem: How both female foreign immigrants (arriving at Battery Park) and domestic country girls (arriving at Pennsylvania Station) were lured to the same evil ends. And its feature length would allow a sustained view of the city, far beyond the quick glimpses of earlier films.”

An added pleasure for the urban architecture scholar is to see the then recently built brownstones and apartment buildings in gleaming condition. In this sense, the film is a true companion to a similar film noir filmed 35 years later, The Naked City (1948).

Cohn later founded Columbia Pictures with Joe Brandt and his brother Harry. Many of the early film moguls were skilled craftsmen in the various jobs of the film industry or were exhibitors who knew their audiences. Although Jack Cohn left no insights into film editing, he may have agreed with Harry’s famous statement on film construction: “When I’m alone in a projection room, I have a foolproof device for judging whether a picture is good or bad. If my fanny doesn’t squirm, it’s good. It’s as simple as that.”

Hollywood wiseacre Herman J. Mankiewicz amended that with: “Imagine, the whole world wired to HarryCohn’s ass.”