by Mel Lambert

Realizing a complex film or TV soundtrack takes a lot of care and attention, together with an advanced degree of collaboration between sound effects editors and re-recording mixers specializing in the same. The former develops the myriad elements needed to detail a contemporary mix, the components of which are weaved together with dialogue and music by the latter to produce a cohesive, immersive whole. CineMontage considers such joint efforts of the sound effects crews working on The 100 television series on The CW network, as well as those on the recently released feature film Trumbo. >>>

THE 100

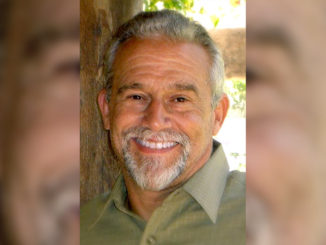

portraits by Martin Cohen

Because of its complex and interrelated story arcs, The 100 represents a unique set of creative challenges for effects editor/ sound designer Peter Lago, MPSE, and re-recording mixer Ryan Davis, working at Warner Bros. Studio Facilities in Burbank. Developed by Jason Rothenberg, the post- apocalyptic drama series premiered during the 2013-14 season; its third season is scheduled to begin airing in early 2016. The weekly series is based on the book of the same name by Kass Morgan, the first in a trilogy.

“Peter and I work closely together to deliver a theatrical-quality soundtrack for one of the busiest shows on TV,” says Davis. “With limited time per episode, we work collaboratively on a tight schedule to deliver amazing tracks for the show, by always communicating our visions to one another so that we remain on the same page.”

“The 100 takes place in the future — possibly 200-to-300 years after our time — but 97 years after a nuclear holocaust,” Lago explains. “The only known survivors came from a series of space stations placed in Earth’s orbit prior to the war. Banding together to form a single large station known as the Ark during Season 1, a group of 100 juvenile prisoners are sent from the Ark to Earth to see if it’s habitable again.”

As a result, Lago had two different environments for which he needed to design specific ambiances. “On the space station, each room had its characteristic sound,” he says. “Since the environment was more than a century old, I developed a creaky vibe to indicate that the station was on the verge of falling apart. For Earth, on the other end, we needed a leafy and airy atmosphere.” Norval D. “Charlie” Crutcher III, MPSE, has served as the show’s supervising sound editor since the first episode, and defined the overall soundscape for each environment.

“The producers wanted the Space Station and the Earth to be characters,” says Davis, who works on Warner Stage 4, with dialogue/music re-recording mixer Rick Norman. “But Earth is not a safe place, since we soon learn that it’s now home to Grounders, who survived the war, and Reapers [Grounders who have become cannibals]. And for Season 3, we encounter the AI-type of creatures that were unveiled in the closing episodes of Season 2.”

“We design all the different creature vocals and movement using a tight combination of designed sound effects and heavy Foley,” Lago explains. “I sometimes leave a hole and see if Foley covers it, but with some backup choices.” Adds Davis, “Peter is different because he carefully reads the script and develops ‘character’ sound for each scene. He really fills it up; some tracks won’t be needed, but they’re there as backups.”

Because of channel limitations, the team has access to a pair of 48-track Pro Tools dubbers for playback into Stage 4’s Neve DFC console, according to Lago, who says he therefore has to be careful with track count. “On a typical episode, I’ll target 48 tracks of mono and stereo hard effects — 32 of mono/stereo backgrounds and 16 of Foley,” he says. “Ryan and I developed our workflow and channel count, together with track color-coding and labeling, while working on Lifetime’s Witch of the East End, which was also mixed here at Warner Post Facilities.”

Although Lago will look in on the stage at the start of each mix session — “we have two busy days to re-record each episode,” Davis states — the effects editor needs to return to his edit suite to continue work on upcoming episodes. ”But I can send a text or instant message to Peter if I need a new effect or if visual effects require extra material,” Davis reveals. “I’m working in the next building,” Lago states, “and can quickly update the effects tracks and make a new Pro Tools session available to Ryan via the media server. I’m just a phone call away.”

Because visual effects elements may not be supplied until the first mix day, Lago says, “I’ll crash down certain things to leave enough room in the track for the new sound effects.” Davis elaborates: “Since we developed a collaborative workflow, I’ll immediately see in the session what Peter has done and what will follow later, via clear labels. I fully understand the way he thinks, which can be a huge time saver.” “Even without picture,” Lago interjects, “I like to let Ryan know about my ideas using carefully labeled tracks.” Davis confesses that he rarely gets to work with someone in a capacity where everything is so clearly labeled and laid out. “Ryan is very collaborative and never throws me under the bus!” Lago asserts.

By way of an example, Davis recalls that in the last episode of the second season, “We had the actors rowing in a boat towards the City of Lights,” to which Lago adds, “And then a giant sea monster attacks them. But we didn’t see any solid visual effects until the final mix. What would it sound like?”

Davis explains, “Our producer Tim Scanlan — who is also directing an episode in Season 3 — tells me a lot about what’s coming up. And when the visuals arrive, I can tweak the tracks while Peter might be cutting a sweetener. That can be very handy because I don’t have to stop the stage; I can always find something to cover. I might need to re-sync an element; maybe an arrow is now coming from the left and not the right. I’ll open the Pro Tools session and use my controller to make those changes, so I don’t need to pull Peter off his show.”

Both Davis and Lago readily concede that sound for a creatively challenging show like The 100 benefits greatly from their finely tuned teamwork. “Having that level of collaboration makes it so much easier for us to develop an immersive soundtrack in the time we have available,” the re-recording mixer concludes.

TRUMBO

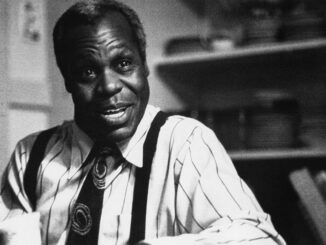

portraits by Christopher Fragapane

During a motion picture project, additional time for editorial and re- recording means that, in theory at least, the sound effects team can work more closely over a longer period of time. For director Jay Roach’s new film Trumbo, written by John McNamara and based on the 1977 book Dalton Trumbo by Bruce Cook, the key was to match filmed action with contemporary newsreels. The film, which opened November 6 through Bleecker Street Media, tells the story of the acclaimed screenwriter’s career — which came to an abrupt halt in the late 1940s, when he and other Hollywood figures were blacklisted for their left-leaning political beliefs. Trumbo is played by Bryan Cranston, with Helen Mirren as his nemesis, Hedda Hopper.

Courtesy of Bleecker Street Media. Photo by Hilary Bronwyn Gayle

“Jay wanted us to develop a realistic sounding soundtrack that matches the monochrome world he re-created from that period, but also with an open, 5.1-channel feel of current releases,” explains supervising sound editor Perry Robertson, a partner in Ear Candy Post with Scott Sanders, MPSE, who served as the film’s supervising sound designer/ editor for sound effects, backgrounds and Foley. “We had early meetings with the director, picture editor Alan Baumgarten and post-production supervisor David Dresher to further define the overall tone and feel of the soundtrack; it’s all about collaboration. Dialogue/music re-recording mixer John Ross was also at those meetings and provided valuable feedback but, because of scheduling, sound effects re-recording mixer Christian Minkler didn’t join the project until a week before the dub started at John’s Ross 424 facility in the Hollywood Hills. It was definitely a team effort.”

“We wanted to retain that overall feel from the pre- and post- World War II periods, using a simplified soundtrack that reflected the time period, with accurate traffic sounds and ambiences,” Minkler says. “We also needed to dirty up our sound to match the mono sound of contemporary archive footage, as we transitioned between stock footage of the Trumbo trials; the voiceover also had to be treated to sound authentic.”

“Alan Baumgarten certainly helped define our direction with the soundtrack,” Sanders confirms. “The trick was to stay out of the way, to be invisible. We wanted to recreate the world of the 1930s and ’40s — a world that sounded a lot different back then, with less traffic and other extraneous noises. I also wanted each of the cars to have its own individual character, with different horns and V8 engine noise.”

Sanders cites one example of a car carrying government agents who plan to interrupt Trumbo’s family picnic in order to serve him with a summons. “There are several shots of the car traveling on its way, intercut with the family at the picnic,” he says. “The vehicle’s character is foreboding and helps play some tension in the intercuts. The car finally pulls up, and the engine’s character and brake squeaks serve to break the jovial mood of the picnic. Another example is Otto Preminger’s arrival at Trumbo’s house; the sound of his Rolls Royce in the close-up is huge, clean and slick; it helps foreshadow the director’s larger-than-life character that we meet shortly after that scene.”

Backgrounds were carefully designed to offer a richness “that we thought would support

the story set in that time period,” Sanders continues. “I also developed a characteristic

sound for Trumbo’s typewriter, which is used in several scenes. And I went back to the production track to salvage practical sounds from the set.”

Foley became a sound character too, according to the sound effects editor.

“We had heavy shoes plus linen and cloth touches; not modern sounding at all. I have an extensive library that I’ve built up over the past 25 to 30 years, and which contains the sound of older cars. I kept asking myself: ‘What does the sound of this car need to convey to the audience?’ If it didn’t work, I started over.”

Sanders delivered a mixture of mono and stereo elements to the stage, to let Minkler “have some fun with the basic tracks,” he says. “I divided the hard effects into 16 conventional mono tracks and 24 mono tracks that had been pre-treated to re-create the newsreel sound from the period. For backgrounds, I delivered 64 stereo elements, in A/B/C format to accommodate screen changes, and had 24 tracks of mono Foley.

“I wrangled everything into shape for Christian, and added volume levels in Avid Pro Tools sessions,” Sanders continues. “I also added labels for elements that I thought might be useful for surround channels, and ambiences that might work on dialogue tracks — but that would be Christian’s final choice, of course. We met for the first time at 424 Post during dialogue pre-dubs after several phone conversations. I asked what Pro Tools templates he prefers.”

“Scott became my right-hand guy,” Minkler offers. “I came late to the project, about a week before the start of the final mix, while John Ross completed his dialogue pre-dubs. But the picture editor talked me through the story arcs, and I caught up pretty quickly. It was a totally collective effort.

Foley became a sound character in Trumbo.

“Playback on the stage at 424 Post was from three Pro Tools sessions containing effects and Foley, background and music, plus dialogue and ADR,” recalls Minkler. “We sat together at the Avid/Euphonix System 5 console and I quickly assessed Christian’s way of working,” Sander adds. “We had three weeks to organize the tracks and get a feel for the 5.1-channel mix. There were no temp dubs, so we moved pretty quickly to print mastering.”

“With the emphasis on realistic sounds from that era, matching the quality of actual to newsreel footage became our challenge, using practical projector sounds and backgrounds,” Minkler explains. “We also re-created the microphone quality of that time, without being too obvious. In essence, we were looking to create a documentary-type feel and capture that magic of the era.”

“Christian is very astute,” considers Sanders. “I could offer input as he worked on the mix, including advising him of sections that were up and coming, as well as making suggestions about the mono feel during the newsreel sequences, the room ambiences I had cut to add richness, and the surround elements.”

Sanders’ philosophy was to select a sound that sells the scene — “one that works with what’s on the screen and doesn’t call attention to itself,” he elaborates. For the newsreel sequences, I had developed seven or eight projector sounds for different scenes — to offer Christian some options and to provide characters for each playback theatre. We chose two or three sounds that were not exactly the same. For example, Kirk Douglas’ screening room has its own unique sound.”

“All the newsreel sounds were treated differently,” Minkler confirms. “Using just a touch of my distortion plug-in — in addition to subtle compression, limiting and EQ to match the period — like during a scene from Spartacus, which was intercut with our actor [Dean O’Gorman] playing Kirk Douglas.”

All in all, the seasoned sound effects editorial and mixing team that worked on Trumbo, which already is attracting a positive Oscar buzz, seamlessly blended sound elements to create a film- centric world from over 60 years ago.