by Peter Tonguette

In his study of silent films, The Parade’s Gone By…, author Kevin Brownlow described editing as “the hidden power.” “Editors are passed over by film historians because their work, when successful, is virtually unnoticeable,” Brownlow wrote. True enough, but when it comes to the history of editors’ screen credits, it is perhaps fairer to say that their craft has only been partly hidden. Since at least the 1920s, editors have been routinely credited on the films they worked on. Until about the 1960s, however, their names were clustered on cards with other craftspeople, appearing in a type size dwarfed by the big credits given to the producer and director, let alone the stars.

In the early days of the talkies, though, this arrangement didn’t especially bother editors like John D. Dunning, A.C.E. “The editors had a pretty good position in those days,” Dunning told Gabriella Oldham in an interview in her book First Cut: Conversations with Film Editors. “Nobody got a very prominent screen credit, even the writers were down in the corner. It wasn’t a big thing then. You felt lucky to get on the title, you didn’t care much how. You didn’t get a separate card. You got mixed up with the cameraman, art director, makeup in various orders.”

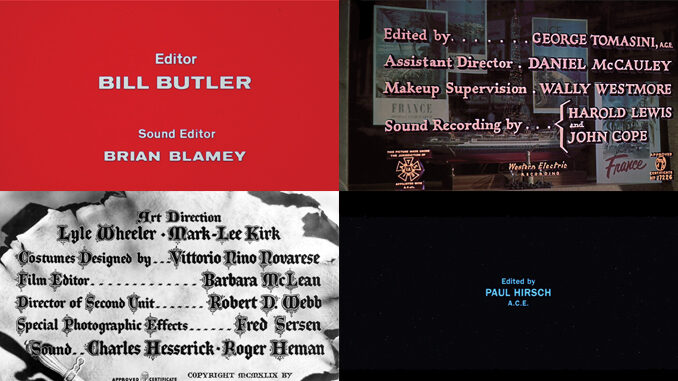

“Various orders” is the term for it, as there was remarkably little consistency in how editors’ credits were presented, even as late as the 1950s. Take four notable films (chosen at random) released in the same year, 1959, by four different major studios: Columbia’s Anatomy of a Murder, Universal’s Imitation of Life, MGM’s North by Northwest and Warner Bros.’ Rio Bravo.

In Anatomy of a Murder, editor Louis R. Loeffler shared a card with the script supervisor, music editor, set dresser and sound. In Imitation of Life, editor Milton Carruth, A.C.E., shared a card with the designer of gowns, makeup artist, hair stylist, assistant director and special photographer. In North by Northwest, editor George Tomasini, A.C.E., shared a card with the color consultant, recording supervisor, hair stylist, makeup artist and assistant director. And in Rio Bravo, editor Folmar Blangsted, A.C.E., shared a card with the director of photography, art director, set decorator and sound.

As confusing as these disparate groupings are, film scholar Vincent LoBrutto, the author of several books on editing, including the just- published Art of Motion Picture Editing, believes that editors still were doing okay, credits-wise. “If you go back and read the credits, when it says who edited it, that’s the editor,” LoBrutto says. “When it says production design or art direction, the first name was the person who ran the department, who may have had nothing to do with the movie.” By contrast, the credited editor was almost always the person who cut the film.

It is widely acknowledged that Dede Allen, A.C.E., was one of the first editors to receive a single-card credit in 1967 (on Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde), though an informal survey reveals that the practice was becoming increasingly prevalent several years earlier. In 1964, George Tomasini was given a single-card credit on Marnie — just five short years after he was listed along with the hair stylist on North by Northwest. On a film- by-film basis, a number of editors began negotiating for a single-card credit, though even as late as 1969, with editing becoming flashier and more conspicuous than it had ever been, it was still not the standard. That year, Donn Cambern, A.C.E., received it on Easy Rider, but Louis Lombardo, A.C.E., on The Wild Bunch did not. LoBrutto points to Peckinpah’s Western as a particularly egregious example of the unfairness of the shared card: “It was edited by the late, great Lou Lombardo, but he’s listed with a bunch of other credits.”

LoBrutto adds, “You have the cinematographer, screenwriter and everybody else in a revered spot. Editors are a major player in the process of making a movie. When I first started getting interested in film, I never liked it when I saw all those credits lined up.”

These days, when a book like 2010’s The Complete Film Production Handbook states, “On an IA show, credit shall read: ‘Edited by,’ ‘Editor’ or ‘Film Editor’” and that “such credit shall be on a separate card in a prominent place,” it is taken for granted. But this was not a contractual right for all editors until the Motion Picture Editors Guild’s 1979 contract negotiations. In research of the Guild Board of Directors minutes conducted by Guild Board member (and author of the “Labor Matters” column in this publication) Jeff Burman, he learned that it was in this contract that “picture editors on theatrical and long- form television will receive ‘up front’ credits if the Director of Photography and Art Directors credits are ‘up front.’”

The subsequent years have seen the pendulum swing in favor of more acknowledgment of editors, on- and off-screen. “The image of the editor has changed drastically,” Richard Marks, A.C.E., told Oldham in First Cuts. “For example, I think in the last five years, if you did a study of film posters, you would probably see 100 percent increase in the number of editors’ names in the credits.”

Brownlow’s adjective to describe the achievements of film editors — “hidden” — applies even more to the work of many sound editors prior to the 1970s. As legendary sound editor Peter Berkos, MPSE, recalls, “I won the Academy Award for The Hindenburg [1975] and I had no screen credit for that picture! The director, Bob Wise, came in one day and said, ‘I’ve been trying to fight for screen credit for you. The best [the producers] could do is let you have credit in printed material.’ And Bob was the president of the Academy! He tried to get it for us, but they were adamant that they would not do it.”

Sadly, for Berkos and his fellow sound editors, it was nothing new. “I worked for 20-some years with no screen credit,” he says. The situation was unchangeable even with the intervention of directors with clout, such as Wise or George Roy Hill, with whom Berkos worked on The Great Waldo Pepper (1975) at Universal. “George Roy Hill gave me a credit,” Berkos remembers. “I told George, ‘You can’t do that. We do not have a mandatory screen credit for sound editors.’ He told me, ‘I’m not used to being told no.’ I said, ‘Oh, then you’re going to fight for it?’ ‘Absolutely.’”

Hill (and Berkos) won the battle, but lost the war. No sooner was The Great Waldo Pepper released with Berkos’ credit than he received a telephone call from a Universal executive, who said, “I want you to know we’re calling the picture back to take your name off.” As Berkos recounts, “In some cases, they sent an editor to projection rooms around the country just to take off that little six-frame shot! They pointed out to me, ‘That’s a negotiable item and we will not let you take it away from us by setting precedent.’”

Shortly after The Hindenburg was released, producer Walter Mirisch was beginning work on the submarine adventure Gray Lady Down (1978). “He told his people that he wanted the person who did The Hindenburg to do the sound effects on this picture,” Berkos says. “But he didn’t know who that was — because there was no credit on the film! He had to start looking for who it was who did the movie.”

When Berkos began a two-year term as president of the Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) in 1963, one of his goals was to secure screen credit for sound editors. In a 1964 letter to Editors Guild business agent John W. Lehners, Berkos reflected on the confusion surrounding his profession, even within the industry, enclosing two reviews of The Lively Set (1964), a film he had recently worked on. “As you can see,” Berkos wrote, “both trades have seen fit to acknowledge the important contribution of the sound editors’ work within this film. The two men primarily responsible for these sounds are Bob Bratton and Frank Warner; however, as you can see, the trades give the credit for this facet of the picture to Mr. Waldo O. Watson, the head of the sound department, and Mr. Josh Westmoreland, the set mixer, whose work it must be realized was discarded and replaced with sounds from the sound editors’ library or from newly created sounds.”

Courtesy of Peter Berkos

As Berkos observes, production mixers and re-recording mixers (formerly known as dubbing mixers) have long received on-screen recognition with credits such as “Sound by” or “Recorded by,” and since 1929, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) has awarded Oscars in the field (under various names, with Sound Recording and Sound preceding today’s Sound Mixing). Although it wasn’t until 1969 that the Oscar went to the individuals responsible for the sound mixing work; previously it acknowledged the studio sound department heads or those listed as “sound directors.”

The situation for sound editors was different, however. Berkos ended his letter to Lehners with a very basic plea: “The main issue right now is to gain a craft credit… The main idea is to let the world know that there is such an animal as a sound editor.” But it would take more than a decade before the efforts of Berkos, in concert with subsequent MPSE presidents, would pay off. He notes, “The initial comment was that they were trying to eliminate credits, not add them!” The studios were anxious about having to credit the multiple sound editors who were typically assigned to a film or series.

“So my initial attempt was to give the sound effects credit to the head of the department,” Berkos continues. “I figured if we got that far, then we could take care of it from there — and that’s exactly what happened. Because we used that approach, we were able to get a sound effects credit. That was the number-one issue, without regard to who was getting that credit. We were limited to one name and so that name was the department head.”

Indeed, even AMPAS didn’t create an Oscar category to honor sound editing until 1963, and then it was not given every year, or was given as a Special Achievement Award — as was Berkos’ Oscar — also under various names (Sound Effects and Sound Effects Editing prior to the current Sound Editing). Since 2004, Academy Awards rules guaranteed three nominations in the Sound Editing category; in 2007, that was expanded to five nominees, like most of the other categories.

Before long, Berkos recalls, the supervising sound editor credit came into being. “That was the one person who assigned a reel to an editor and ran the reel with that editor to tell them what has to go into the reel or what kind of work is necessary,” he explains. “That person became the supervising sound editor and then got the credit.” So, on the 25th anniversary of the MPSE in 1978, then-president Lawrence Carow was able to inform the membership that “sound editors now hold their heads high as recognized creative contributors to every motion picture and television film with screen credit recognition.”

It was a long road for music editors, too. In his 35-year career as a music editor at Warner Bros., Eugene Marks, MPSE, worked on many classic films and series, including The Exorcist (1973) and Blazing Saddles (1974), but until the early 1970s, on-screen credit for his work was far from routine. Before that time, “If some producer out of the kindness of his heart decided to give credit, he would,” Marks says.

“So many people don’t even know what a music editor is,” Marks continues. “They ask me and I say, in the briefest possible sense, that he’s like the technical right arm for the composer. But it’s a lot more than that. You’re in for the entire process from the time a picture is spotted to final scoring sessions to editing the tracks. You know, if they take a picture out and preview it and they come back and make picture changes, they’re not going to call the composer and an orchestra in and re-score it. The editor has got to make the music still fit the picture changes. It’s quite a challenge.”

Berkos is just as eloquent as he describes the integral role of sound editors: “The sound editor is on an equal plane with the music composer. When we get our assignment, we get a cue sheet that we’re going to fill out with sound effects. That cue sheet is just as bare as the music sheet that the composer’s starting with.”

He adds, “Whenever you see a special visual effect, that’s only half the job. It’s not until you put sound to that visual effect that the senses are satisfied.”

And it was not until the day when all editors were satisfactorily credited that the Editors Guild and its members’ sense of fairness began to be satisfied.