by Edward Landler

By the time most of you are reading this, the 83rd Academy Awards will be history and their results another entry for the record books. We can now collect our winnings in the Oscar office pool (or not) and set aside debating the collective wisdom of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in its consideration of the films and filmmakers of 2010.

But before moving past last year’s accomplishments, CineMontage considered that the achievements of one of the Guild classifications have been perpetually overlooked by Oscar—the work of the music editor, who compiles, edits and synchronizes music in the creation of a film’s soundtrack. While music editors are included as part of the team in some of the Creative Arts Emmy Awards’ Sound Editing categories for television, as well as a few of the Motion Picture Sound Editors’ (MPSE) Golden Reel Awards––chiefly the ones acknowledging music in film and TV––there is no high-profile recognition from the gold standard of movie awards ceremonies.

In an effort to rectify this snub in some fashion, we asked a sampling of distinguished music editors what they thought of such an award, as well as which film in 2010 they feel should have received the hypothetical Oscar for Best Music Editing—and why.

Whether they selected films or not, the music editors voiced a range of opinions about whether an award for Best Music Editing was even a good idea. Their perspectives on the question provided some insights into the nature of their work.

“This is great fodder for discussion,” claims Christine Luethje, MPSE, who worked on Moulin Rouge and Ali. “The more people talk about it, the more they understand our contributions to the process.” Elaborating on that contribution, Jim Schultz (Inglourious Basterds, 3:10 to Yuma) adds, “Essentially, the music editor helps to facilitate the director’s vision.”

Jason Ruder (Dreamgirls and Crazy, Stupid, Love) confesses that he could see how a music editor would be worthy of an Oscar. “But it all comes down to the relationship with and the need of the filmmaker,” he says by way of qualification. “Some directors enter the cutting room with music specifics already chosen or scripted. But when the creative need arises, a music editor is responsible for taking on a vision and setting the tone and style of the score and songs during the temping and preview process. If those musical concepts are well done, it will highly impact the end and overall result of a film.”

Regarding the various ways a music editor might work on a project, Angie Rubin, MPSE (The Company Men, Sex and the City)––who represents music editors on the Guild’s Board of Directors––says, “Every single show is different. The music editor usually starts with a blank slate––before the score exists. I come in early and help design the template that the score will eventually replace. Some music editors just do temps. Some music editors just work with the composer once he or she is hired. And some have the joy of being involved from beginning to end. Hopefully, regardless of the time we’re on, the music editor is the connective tissue that helps the composer communicate with the director.”

Music editors often work in a satellite location off the studio lot, or sometimes right next to the picture editor, according to Luethje. “We’re very independent of the sound and effects departments until temping or dubbing, when all the elements are merged,” she explains. “Depending on the budget, we’re hired at different stages of a production.”

“Music editing at its core—which includes providing and shaping the temp cues on which the film’s score is modeled—represents terrific craftsmanship,” says Richard Henderson, MPSE (Into the Wild, Borat). “I wouldn’t want the Oscars to be any longer than they already are,” he adds. “But it’s obvious that music editors do Oscar-quality work.”

Some music editors, though, had reservations about this imaginary Oscar.

“Honoring the music editor is a great idea, but there are many reasons why it would be hard to pull off,” opines Curt Sobel (Nine, Ray). “For one thing, you’d have to figure out how to define what a music editor does in a way that the voter can identify on the screen.”

Erich Stratmann (The Beaver, Rent) flat out doesn’t think there should be an Academy Award for music editing. “Unlike picture editors and cinematographers, one can make a film without a music editor,” he offers. Also, just because the score is great doesn’t mean the music editor made a more significant contribution than, say, the music mixer. Many times, we are very involved with the creation of the score, but sometimes we’re technical shepherds, delivering the composer’s work to the mix.”

Agreeing that such acknowledgement for music editing would not be a good idea, Helena Lea (Cookie’s Fortune, Dr. T and the Women) says, “I find that the craft of music editing is difficult enough to judge. Add to this the fact that the majority of the voters in the Academy are not musicians themselves and you’ve got, in my point of view, an award category that is nearly impossible to evaluate objectively.”

Dan Pinder (Gulliver’s Travels, The Dark Knight) calls the idea “a futile pursuit; even as a music editor, it’s hard to observe and judge the work of your peers.” Stratmann adds, “If I watch a movie and hear a music editor’s work, then there’s a problem. Good score editing should create a soundtrack that is seamless; you shouldn’t even know there was a music editor.”

Craig Pettigrew (TV’s Ugly Betty and Monk) doesn’t even see how one would judge for a specific music-editing award––“unless you have inside information about the production and how the score and the songs were handled by the music editor,” he says. “A music editor could be on a project before the composer; and the composer sometimes brings on his or her own music editor.”

Stratmann notes that to gain a nomination for the MPSE Golden Reels, a music editor must make his case. “You have to write a report detailing the work done,” he explains. Tom Kramer (Valentine’s Day, Jackie Brown) agrees, adding, “Unless they know the history, there would be no way for the voters to know what the music editor did. If we do our job well, nobody knows.”

Lea elaborates: “The most creative and complex music editing in many instances is done in pictures most people have never heard of. These are the projects that present the most editing challenges—precisely because the picture itself is not working.”

Some of the music editors offered compromise positions on an award. “When the Grammy for Album of the Year is awarded, the producer, the recording engineer, the artist and the mastering engineer all receive it,” says Schultz. “In the same fashion, we should be recognized along with the composer for best original score—the exception being if the composer says ‘No’ to that.”

For his part, Pinder sees music editing as a form of production. “Perhaps the music editor would best be served by being recognized as part of a team contributing to existing categories—Best Original Score and Best Original Song—a kind of esteem-by-association.” Strat-mann agrees: “The best situation would be to include the music editor with the Best Original Score recipients, perhaps also including the score mixer.” Pettigrew has an even more modest proposal, suggesting, “I’d rather have the composer thank the music editor from the stage.”

Recommending a more music-oriented approach to such an Oscar, Sobel says, “Unfortunately, it would be difficult for the voters to distinguish what a music editor creates in most films. But musicals would be different because the music is dominant. You can clearly visualize and hear what was accomplished.”

Despite the discussion and debate on the wisdom––and practicality––of establishing an Academy Award for Best Music Editing, several music editors ventured some Oscar-worthy selections for such an honor for the films of 2010.

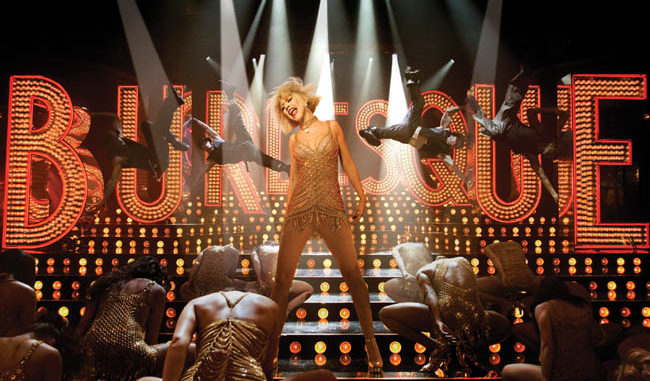

Reiterating his idea for a specific award for music editing for a musical, Sobel named two recent films and their respective music editors: Country Strong (Fernand Bos, MPSE, and Philip Tallman) and Burlesque (Joseph Magee, CAS, Todd Bozung and Chris Newlin). “In a musical, Academy voters can best recognize the music editor’s contribution,” he says. “There were pre-records and playback, lip- and instrument-synching–– and the responsibility for those processes falls on the shoulders of the music editor.”

Henderson also put forward two films: “First, The American, with Peter Clarke as music editor, made me aware of the skill of the people working on it—more than just hitting the mark with music, much more subtle than that. There’s an organic cohesion when the music just merges with the picture and doesn’t call attention to itself. Good music editors help that merger to occur.”

“And also The Social Network (Marie Ebbing and Jonathon Stevens),” he adds. “Composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ use of sequential synthesis fit the cyber world of the film and spoke to alienation and loneliness. There’s a ‘Rosebud’ moment at the end when Mark [Jesse Eisenberg] tries to ‘friend’ the girl who broke up with him. The score crystallizes the tone and theme of the story.”

Pettigrew selected Toy Story 3, whose music editor, Bruno Coon, MPSE, often works with Randy Newman. “The music is so important to the film,” he explains. “I’ve done a lot of animation, and frequently the music editor assists the composer through tempo mapping—massaging the pace of the music to the pace of the visuals. In live action, you don’t have to hit things in the same way. Animation is far more exacting.”

Rubin cited 127 Hours and John Warhurst: “The music is really good—really effective in its texture and ambience. Everything about it worked. The end was a tough moment to pull off, but the last cue—when Aron [James Franco] makes it out of the canyon and finds the other hikers—paid off. It was emotional, but not over the top. It was also my favorite movie of the year.”

Both Luethje and Ruder chose Inception, with Alex Gibson as supervising music editor and Ryan Rubin as music editor. “The music was different,” Luethje says. “It didn’t sound like any other picture. It had a unique signature—a fairly simple theme used in a very complex way. I love it when thematic content is carried throughout a story. Here, the theme was musical but with a textural sound-design feeling. It didn’t get in the way; enhancing the story without distracting from it.” Ruder adds, “Alex Gibson is one of the strongest and most creative music architects out there. His hard work and ideas always seem to have a fine way of executing the director’s vision.”

The others music editors declined to cite a film. But Kramer tongue-in-cheekily suggested another compromise: “I would propose an Oscar for the Best Final Score Most Resembling the Temp Track.”