by Michael Goldman

Lately, the buzz surrounding the arrival of the Academy Color Encoding System (ACES) as a standardized, device-independent, color management and image interchange system meant to be applied to present-day and future workflows has ramped up in intensity. The ACES project began over 10 years ago when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences gathered industry experts together to develop, essentially, “a common digital interchange file format suitable for long-term archiving,” explains Andy Maltz, managing director of the Academy’s Science and Technology Council, which heads up the ACES effort.

“Over the course of development, ACES evolved into the digital replacement for the industry’s production infrastructure that we lost when we moved away from film,” he continues. “We had well-known spectral response curves, standards, metadata, latent imagery, keycode labeling and so on for a few common workflows. Everything was well known and consistent within lab tolerances — that is, when we worked with film-based technologies and workflows. But when we moved away from film and into the digital world, there were no standards and no consistency. So ACES was designed and built as a suite of standards and best practices, providing for a standardized production infrastructure.”

Keeping pace with these continually evolving technologies is why Maltz points out that there is every intention to eventually produce an ACES Version 2.0, and a versioning system has already been built int0 ACES Version 1.0 to accommodate future development.

Now, after years of field-testing pre-release versions of ACES on selected projects, ACES version 1.0 is finally available as, according to the Academy, “the first production-ready release of the system,” which includes support for “a wide variety of digital and film-based production workflows, visual effects and archiving.” On the ACES Website (www.oscars.org/science-technology/sci-tech-projects/aces#field-tabbed-content-tab-5), a list of production partners illustrates that the standard has already been built into numerous camera and color-correction systems with more on the way, as was announced by several companies this past April at NAB.

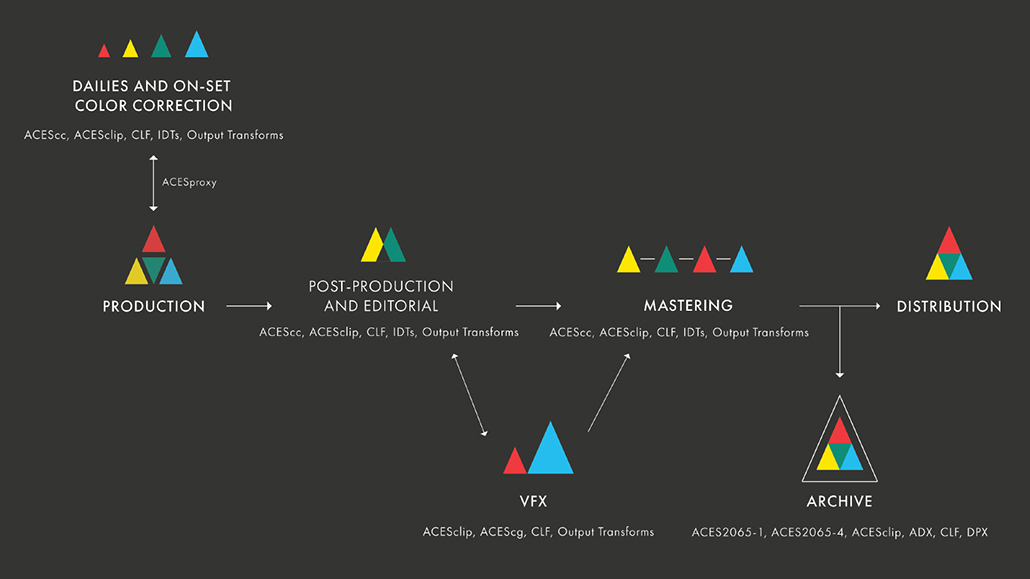

Equally crucial has been the effort to educate the industry about how ACES impacts different sectors of the production chain. While much of the early focus was on bringing equipment manufacturers and service facilities into the ACES fold, educating the creative community will be an ongoing, long-term effort, Maltz suggests. Furthermore, until now, much of the initial outreach has focused on the image capture, dailies, visual effects and digital intermediate processes.

For the color pipeline, ACES is “a defined color space and working space where you will do your color correction,” in the words of Joshua Pines, Technicolor’s vice president of Imaging Research and Development, but speaking as a member of the Sci-Tech Council. “It’s the image state pipeline, and describes how you get from various cameras into a common color space where you do your color correction how you apply a viewing transform and how you then go out to different display devices. But ACES is very specific in that once you get all that material into the color space, it has nothing to say about how you do the color correction. We are merely defining how you transform the images and get into ACES, and then, how you view it when you are done doing color correction.”

ACES IN POST

Now, the Academy is trying to get the message out to the post-production community on how ACES potentially impacts the editorial team specifically. The intent of ACES is to enable the highest quality possible color management all the way from image acquisition through distribution. It is also to simultaneously ensure that there is a common standard for all deliverables via the implementation of an encoding system that preserves as much dynamic range and color information as possible from the originally captured image. So how deeply do editors need to worry about all the associated details anyway? Yes, modern editors frequently deal with color for creative purposes or to solve problems, but don’t they expect the nuances and technical details of “color management” to be left to others?

According to Maltz, the answer to these kinds of questions is a basic “Yes.” Editors do want such details to be largely invisible inside the editorial suite. And to a large degree, that is one of the key points of ACES; it can improve the product traveling through the editorial department and potentially make that journey more efficient, but without disrupting the nature of the unique work being done in editorial, he believes.

“One of the biggest complaints we hear from productions, cinematographers, directors and colorists is that at some point along the line, if it is not a well color-managed project, when they get to the digital intermediate, the director says, ‘That is not my movie,’” Maltz explains. “This happens because there was no color management that connects with editorial; if editors adjusted color because a director asked them to, there is no mechanism to communicate those changes to the colorist in the DI suite, and the director sees different colors there. More sophisticated projects generally incorporate some form of color management, but many projects don’t have the resources to do that.

“ACES provides specifications and best practices for color management with standardized metadata and transforms that can be supported by the editing systems that editors are using so that, even if they make the simplest color adjustments in the editing suite, they will be doing so in a way that can be communicated to the DI suite,” he continues. “The pieces that the editing systems need to support are the ACES Display Transform, ACES clip metadata, and the ASC-CDL [American Society of Cinematographers Color Decision List format for exchanging color-grading data between platforms manufactured by different manufacturers], so that when you get to dailies created by a dailies generation system, the files were produced knowing what the display color chain is, and with the metadata files necessary to communicate the editor’s color adjustment to DI, visual effects or anywhere else.”

Maltz adds that the ACES initiative therefore “makes a very strong statement about monitor calibration throughout the entire imaging chain,” including the editorial suite, since “ACES provides the mechanism to communicate the color intention from set to editorial to dailies viewing to DI — and to and from visual effects — all in a standardized way. ACES provides display transforms for the most common display types and viewing environments.”

And the issue of monitors has been a question that concerns editors, since some of them point out that many editing suites rely on prosumer monitors at best, if not solely on computer monitors, with limited calibrating capabilities, even under the best of circumstances. Editor Shelly Westerman is one editor who worked on recent major features entirely within the ACES workflow. She used pre-release versions of ACES, when she co-edited The Wedding Ringer in late 2014 and also used ACES protocols while co-editing About Last Night between 2012 and 2013.

The reason ACES is not a cure-all is that there is simply no replacement for the human role in the process, nor for typical limitations in production that can cause variances in imagery.

Westerman reports that on both projects, the involvement of ACES was “really quite transparent” for the editors in most respects. But she does add, “We still struggled with monitor setups; we work in an offline environment and traditionally there have always been monitor variances and struggles to be able to confidently judge color.”

She attributes this to the fact that her team relies on prosumer monitors in the editing bay limited to Rec. 709 calibration, and feels it is likely impractical to think that editing rooms will ever be routinely configured with the same kind of monitoring technology as digital intermediate suites.

But nevertheless, Westerman says, “We clearly have more consistency than we had before.” Besides, there were other obvious efficiencies working under the ACES umbrella from the editorial department’s point of view. For one thing, the creation of preview versions of the films was more efficient for the simple reason that Westerman and her crew didn’t have to step back and take an extra day to color-correct preview versions. “That saved us a lot of time and energy,” she says. “We were able to output an HDCAM-SR tape directly from the Avid and take it straight to a theatre. In the past, we would never preview an Avid cut without having someone do a color-timing pass first. Now, with ACES, it’s not an issue because the dailies color grade or on-set look has already been applied.”

Similarly, for visual effects’ collaboration, Westerman says that the utilization of ACES “streamlined our process in that our assistants would create EDLs with CDL information included. The digital intermediate vendor would pull the plates and provide the CDL information and a viewing LUT to our visual effects producer and his team, and they could get to work immediately. We didn’t have to set aside time to pre-color-time the plates, which was a definite plus. If an adjustment did have to be made without editors present to give input about the look of the show, our colorist Trent Johnson already had the information about the DP’s intended look— since we were utilizing ACES.”

Furthermore, the editor’s relationship with the colorist regarding the digital intermediate process did not change creatively, according to Westerman, but became more efficient. In her career, she says she has traditionally participated in the DI and in “helping to create a foundation for the final DI work” during the editing process. However, “As ACES streamlines the process, the amount of time we need to spend in the color-timing sessions decreases,” she adds. “With this process, it is much easier for the colorist to do his own pass, then call us in for a review session. He already has a clearer understanding of what the DP, director and producer intended, with adjustments from editorial reflected in the Avid QuickTime reference. We used to camp out in the DI room or the lab. Now, we color-time the movie in significantly shorter time than we used to, because ACES allows things to fall into place more efficiently.”

Colorist Trent Johnson handled that job on both projects that Westerman edited. In fact, he worked on some seven movies between 2013 and 2014 that were done using a pre-release version of the ACES spec. “ACES is no panacea, but while it is not an auto-color-corrector, it certainly is an auto-confidence-enabler, ” he says.“It’s a huge benefit to have confidence that I’m seeing the same images as everyone else working on the movie and, in some areas, enjoying a huge time savings as well.”

According to Johnson, the beauty of ACES is that it is transparent to him as the colorist. “I simply see the same color they saw on set, as it was baked into the dailies,” he explains. “When I start a show, ACES is turned on in my Baselight color corrector, and any on-set color corrections — CDLs — are already in my color list, as they are imported from the client’s EDL. The visual effects vendors see the same color on their monitors, as they can use an ACES LUT as well, even if they aren’t using Baselight. When I receive the visual effects shots, they drop in where I had just a backplate, and keep the same color correction.”

Both Johnson and Westerman emphasize that the reason ACES is not a cure-all is that there is simply no replacement for the human role in the process, nor for typical limitations in production that can cause variances in imagery.

“There can be variances in dailies between A, B, and C cameras from time to time,” says Westerman. “A lot depends on the camera crew and those processing the media, applying looks, and entering crucial metadata. If a setup is missed or a look isn’t applied properly, then a scene will be off. Plus, second unit and B-roll frequently does not have any look applied on set, so we often have to match to that in the Avid. The science is great, but it’s ultimately dependent on the team that is preparing the media.”

“The other wild card is the cameras themselves,” adds Johnson. “If one of three cameras is different for some reason — perhaps it’s using a vintage lens with a different color tint or is off angle — they may not all be color-balanced the same. But that problem pre-dates ACES, and ACES won’t solve it for you. The dailies colorist would have to adjust the CDL for that camera to correct it.”

The editor’s relationship with the colorist regarding the digital intermediate process did not change creatively, but became more efficient.

A PARADIGM SHIFT?

Are there any areas in which ACES changes the paradigm for editors and colorists, or otherwise concerns them? For some, one topic of discussion has been the aforementioned ACES Display Transform, a component of the full ACES package formerly known by the more technical engineering monikers Reference Rendering Transform (RRT) and Output Display Transform (ODT). Display Transforms are components designed to be a common standard for converting scene-referred ACES imagery (similar to a film negative) along an aesthetically pleasing S-shaped tone curve within an ACES Project Committee-chosen color gamut and dynamic range that, frankly, “is a great starting point for colorists,” as Maltz puts it, when displayed on any ACES-calibrated output device. It is, in other words, a way “to get a balanced and pleasing out-of-the-box picture that would otherwise require hours of colorist time for basic technical grading and camera-matching,” Maltz adds.

Some industry types, including colorists, however, were concerned that the tone curve and related components were “too aggressive in the early days for making a great picture out of the box, and this made it harder for colorists to do their job, which is to make creative adjustments to colors,” he continues. There was, he says, some early confusion about whether colorists “had to use the default ACES look” when rendering out imagery for initial viewing, even though “the default look was always intended to be a flexible starting point, not the finished product.”

In other words, as ACES went on to become “official,” would facilities and projects that decided not to use that tone curve, preferring instead to apply one of their own choosing, still be considered ACES-compliant in the long run?

Maltz says another component of ACES, known as the Look Modification Transform (LMT), addresses this concern. The LMT, among other things, enables customizing the starting point for image data by putting a user-defined “default look” into the ACES pipeline before getting to the Display Transform viewing stage, allowing colorists to build customized looks inside ACES.

“LMT designers have to pay attention to maintaining the extremely high dynamic range and wide color gamut inherent in ACES, which is a departure from the current practice of working within the reduced dynamic range and gamut of today’s display devices,” Maltz elaborates in response to concerns that the current LMT solution might not preserve enough dynamic range latitude or color gamut information in archived versions of the content, which might be needed for future versions of current releases. “Doing so is critical for protecting content for future display technologies.”

Keeping pace with these continually evolving technologies is why Maltz points out that there is every intention to eventually produce an ACES Version 2.0, and a versioning system has already been built int0 ACES Version 1.0 to accommodate future development. These kinds of issues and other concerns or additional features that user input eventually brings to the fore can get addressed as ACES matures. “But first, the industry needs to establish some stability around ACES 1.0,” Maltz points out. “We need some serious adoption before we can get to Version 2.0.”

And speaking of input, Maltz says the entire industry, including the editorial community, is encouraged to provide input, questions and concerns to a special e-mail address: aces@oscars.org. Additionally, he says, “We are also preparing an end user community forum to enable filmmaker-to-filmmaker conversations.” He urges the editorial community to check out the ACES website for more information and updates on upcoming ACES-related events.