by Ray Zone

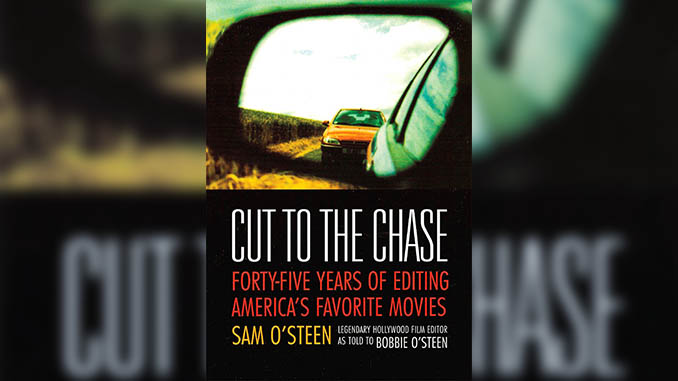

Cut to the Chase

Forty-Five Years of Editing America’s Favorite Movies

By Sam O’Steen, Legendary Hollywood Film Editor

As told to Bobbie O’Steen

Michael Wiese Productions

249 pps, Paperbound, $24.95

ISBN 0-941188-37-X

Few people in the motion picture business have had a career like Sam O’Steen. He is the man who edited landmark films such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), The Graduate (1967), Cool Hand Luke (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Chinatown (1974). He was an honest man and his truthfulness as well as his great humor is readily apparent in this oral history.

With an in-depth interview by Bobbie O’Steen, Sam’s wife of 23 years, the result is one of the very best anecdotal histories of filmmaking in print. In this case, the intimacy shared by interviewer and subject pays off with great inside stories about film personalities and the real stuff that happened behind the scenes with the making of now-classic motion pictures from the 1960s and ‘70s, an era that has been characterized by movie buffs as the “Golden Age of Cinema.”

Structured in a Q&A format with occasional sidebars on individual films and directors, the book reads like a dream for anyone interested in how filmmaking actually works. O’Steen didn’t hesitate to call a spade. Yet this quality did not stop him from becoming the highest paid editor in Hollywood. In so many ways, this book is all about personalities, from Jack Warner and Frank Sinatra to Mike Nichols and many others.

O’Steen started out from hardscrabble poverty and began working at Warners in the print shop in the 1940s, where he toiled for ten years. At this time, he attempted to get into editing. “It was impossible,” he said, “but it was a dream I had.” Editor Fred MacDowell gave him a start as an apprentice on a John Wayne film called Blood Alley. On the first day, O’Steen walked into the cutting room where he met Ralph “Pappy” Dawson, the Academy Award-winning editor for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), Anthony Adverse (1936) and The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938). Dawson told him, “So you want to be a cutter, huh? Well, let me give you two pieces of advice. First, never wait for a picture; take the one that’s offered. Second, after you start cutting, put the film on the shelf to let it heal. If you pick at a sore it’ll never heal, but if you put it aside for a couple of weeks, you’d be surprised how objective you’ll be.”

Editing has to be justified in terms of how it serves the story.

During the requisite eight-year term that O’Steen served as an assistant editor, he created a couple of useful inventions. The first was to switch to a straight razor blade on the splicer and dispense with the serrated blade, which would pick up dirt. O’Steen’s second invention was a portable rewind, which he used to splice in optical shots in the back seat of a car on the way to a film preview. After working as an assistant editor on A Summer Place (1959), directed by Delmer Daves, O’Steen was asked by the director to edit his next picture. But he still had four more years to serve as an assistant. But on the very day his eight-year term was up, O’Steen’s phone rang and it was Daves on the line who asked him, “You ready now?” “Yeah, I’m ready,” he responded, and began work as an editor on Youngblood Hawke (1964) at the age of 38.

O’Steen then worked with director Curtis Bernhardt and edited a string of films with Sinatra that included Robin and the Seven Hoods (1964), Marriage on the Rocks (1965) and None But the Brave (1965). He began his long-term association with Nichols on Virginia Woolf in 1966, but the director was initially opposed to working with him. He was “dead set against me,” said O’Steen. At their first meeting, Nichols asked if it would be possible to shoot overlapping dialogue. “If you shoot it, I can get it together,” he replied. Nichols found that interesting because numerous editors had told him that it was impossible. Virginia Woolf became the first picture intentionally shot with overlapping dialogue. “Mike, coming from the stage, knew the value of it,” says O’Steen. “There’s a reality to it, because in life we overlap constantly.”

The editor’s solution for the overlapping dialogue was to recommend shooting with two cameras, record separate sound tracks for each camera and mix them together using matched timecode for sound and picture. “That way, they would always be in sync,” he said.” I could cut anyplace I wanted to.”

Around this time, O’Steen developed a saying which reminded a director not to become too attached to a moment or a scene. “Movie first, scene second, moment third,” noted O’Steen. “That is the order of importance for everything.” With this rule, editing has to be justified in terms of how it serves the story.

In so many ways, this book is all about personalities, from Jack Warner and Frank Sinatra to Mike Nichols and many others.

For Virginia Woolf, Nichols wanted Andre Previn for music scoring and objected to screenwriter Ernest Lehman’s signing of Alex North. Nichols persisted, which resulted in Warners throwing him off the lot. “Mike and I were working in the cutting room,” explains O’Steen. “We’d just finished shooting a couple weeks before, when they told him he had four more days to finish the movie.”

Nichols and O’Steen worked day and night for four days to complete editing on the film. “I remember at one point I was sitting on a stool, laughing at something, and I was so tired I actually blacked out,” the editor recalled. The sound mix was completed by O’Steen. Nichols made periodic calls to listen to the sound track in progress over the telephone. That was a particularly brave action O’Steen took, which could have gotten him blackballed by every studio. “It’s amazing, really, to think that there were seven or eight guys [studio heads] who could just call each other,” said O’Steen. “And that would be the end of you.”

So much of Hollywood history consists of recollections by pioneers like Sam O’Steen. This is one of the best I’ve read, and a must-read for editors interested in how the craft evolved.