by Edward Landler

Prisons are not visually attractive. That may be why prison movies were not a significant genre during the silent era. But after the introduction of talking pictures and as sound technology was refined, the 1930s saw the studios turn out over 60 movies set in penitentiaries.

Allied Artists Pictures/Photofest

Attuned to melodramatic situations by its very nature, sound underscored the ambience of long confinement and the expression of emotions and conflicts literally pent up until they would erupt into violence. Audiences drawn by action and brutality could also identify with themes of innocence and guilt, rehabilitation and redemption, escape and official corruption. While most prison films to this day vividly depict the hardships of incarceration, rarely do they attempt more than a token reference to the social and economic causes of crime and its consequences.

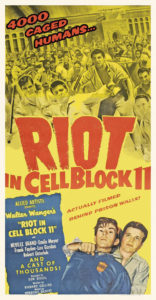

On February 28, 1954, Allied Artists released Walter Wanger Productions’ Riot in Cell Block 11, a film shot at Folsom State Prison in 16 days on a budget just under $300,000. Its Variety review read, “The picture doesn’t use a formula prison plot. There’s no inmate reformed by love or fair treatment…nor are there any heroes and heavies of standard pattern.” Howard McClay in the Los Angeles Daily News called it “the best film of its kind to ever hit the screen.”

During its initial run 65 years ago, Riot grossed over $1.5 million dollars, a phenomenal amount for essentially a B-picture. The British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) nominated it for Best Film from Any Source and its star Neville Brand for Best Foreign Actor. Director Don Siegel was nominated for the DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement. The movie also inspired Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller to write “Riot in Cell Block Nine,” the Robins’ (soon renamed the Coasters) first R&B hit single, released in June of that year.

From its conception, producer Wanger intended Riot to speak directly to the 30 prison riots that had occurred in the United States in the previous three years. In a terse and exciting 80 minutes, the film’s narrative focuses on the riot itself through a multi-dimensional view of the interactions of sharply drawn characters, offering a complex perspective of American society through the institution of prison.

A month before the movie opened, Wanger told Variety, “I wanted to make a picture that would make the public realize what a failure the prison system is today.” He blamed “vested interests” of the underworld and politics for supporting the system’s major faults: “…idleness, failure to separate and medicate psychopaths, overcrowding and releasing prisoners before they are ready to resume normal life.”

The producer was motivated by personal experience. Like the film’s character of the Colonel, a retired military officer in prison for manslaughter, Wanger realized, “…anyone can land in prison — just like that!”

Late in 1951, certain that his wife, actress Joan Bennett, was having an affair with her agent, Jennings Lang of MCA, Wanger shot Lang in the groin in a Beverly Hills parking lot. Only slightly wounded and wary of damaging Bennett’s career, Lang refused to file charges, but authorities prosecuted. A leading producer for 20 years and two-time president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Wanger had not recovered financially from his big-budget 1948 flop, Joan of Arc starring Ingrid Bergman, and his friends (among them, Samuel Goldwyn, Walt Disney, Darryl F. Zanuck and Walter Mirisch) contributed to his legal expenses.

Despite pleading temporary insanity, the producer was sentenced to four months in the Los Angeles County Honor Farm in Castaic. According to Matthew Bernstein’s 1994 biography, Walter Wanger: Hollywood Independent, upon his release in June 1952 after serving 98 days of the sentence, Wanger told the press that the prison system “is “the nation’s number one scandal… I want to do a film about it.” The difference between Castaic and San Quentin or Folsom was, he added, “a matter of degree not kind.”

Allied Artists Pictures/Photofest

Seeking backing for the project, the ex-convict producer approached Mirisch, head of production at the “poverty row” company, Monogram Pictures. With television taking audiences away from theatres, Mirisch was transforming Monogram into Allied Artists (AA), hoping to raise the quality of studio productions to break into the more profitable urban “early-run” market.

Mirisch put Wanger in charge of other AA projects while he developed his prison script. Early in 1953, Wanger discussed the movie with Richard Collins, a writer Mirisch had hired for another project. A former Communist Party member, Collins was one of the original “Hollywood 19” subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee and blacklisted by the industry until, unlike the jailed “Hollywood 10,” he named names as a co-operative witness in 1951. At Allied Artists, he earned $500 a week; before the blacklist he had made up to $1,500 a week.

Collins started work on the screenplay in March with Wanger guiding the tone and the shape of the narrative. The story was drawn from the actual events of the Jackson, Michigan State Prison riot of April 1952, in which 2,600 convicts held nine guards hostage and caused $2.5 million in damages. The movie’s riot leaders were based on the leaders of the Jackson riot, Earl Ward and “Crazy” Jack Hyatt, identified by prison authorities as psychopaths.

Based on Jackson’s assistant deputy warden Vernon Fox, the film’s warden sees the need for reform and sympathizes with the rioters’ demands. The film rioters’ demands were the same as the demands of the Jackson inmates: remodeling cell blocks to give inmates more room and light; separating the mentally disturbed for medical treatment; getting rid of manacles, leg irons, chains and brutal guards; and no reprisals against riot leaders and participants. Wanger added one demand in the screenplay: “Teach us a trade so when we get out we’ll be able to hold down a job.”

He also insisted that Collins eliminate the scripted opening scene starting with a shot of a robin in the warden’s wife’s garden just outside the walls. Instead, he wanted him to drop the wife and open with newsreel footage of prison riots of the early ‘50s.

From the first shooting script to the final cut of October 20, the producer kept up a continuing correspondence with Production Code Administration (PCA) chief Joseph Breen. On June 17, Breen acknowledged that Wanger “had already eliminated references to perverts and homosexuals,” but requested that “the intimate parts of women, specifically the breasts…be fully covered at all times,” referring to pin-up pictures posted in convicts’ cells.

Breen still maintained his major objection to the script on July 21 — “that it definitely throws sympathy to the side of the criminals as opposed to constituted authority and the administration of justice.” The PCA gave its approval in October after Wanger described his research, which included listing the penal authorities consulted: Folsom warden Robert Heinze, associate warden William Ryan, and California Department of Corrections director Richard Magee.

On July 22, Siegel was hired as director for a $10,000 flat fee. Starting in the industry at Warner Bros. in 1934, he worked up from the stock-shot library to editing to founding the studio’s montage department, directing second-unit shoots and editing the material into montages for many Warner pictures until he began directing features in 1946. His early experience is apparent in Riot’s opening prison montage and its smooth transition into the film’s narrative. Editor Bruce B. Pierce, ACE, assembled an early cut while Siegel shot on location, and they worked closely together through post.

As to working with Collins on the final draft of the script, the director told Peter Bogdanovich in a 1968 interview in the English film magazine Movie, “I felt this picture had something to say and didn’t choose sides… I molded the script so it would have the excitement it does have. Dick Collins wrote it all — but I think he would admit I contributed.”

Wanger and Siegel scouted Alcatraz, San Quentin and Folsom as possible locations, deciding on Folsom when they learned the prison had an empty 1880s-built two-story cell block which the production could take over completely. Despite Siegel’s guarantee of a 16-day shoot, warden Heinze was reluctant to permit it because a movie shoot went 11 days over schedule in 1951.

To ease the warden’s mind, Siegel introduced him to the crew members who were on the scouting trip — most importantly, he thought, cinematographer Russell Harlan, ASC, who lensed regularly for director Howard Hawks. But when Heinze met the production assistant on his first movie job (hired with a recommendation from then-California attorney general, later governor, Edmond G. Brown, Sr.), he recognized Sam Peckinpah, the son of prominent Fresno judge Denver Peckinpah. According to Siegel, in the 1993 A Siegel Film: An Autobiography, the warden made the future director the film’s production liaison, telling him, “If you run into any trouble, or have need of any information, be sure to see me, personally.”

Principal photography began August 17 and the lack of recognizable stars strengthened the authenticity of the setting. Like Brand, who had been the fourth most decorated soldier in World War II, fellow actor Leo Gordon had also fought in the war and also used the GI Bill to study acting. But the huge and intimidating Gordon had served five years in San Quentin for armed robbery and Heinze did not want him in his prison for any reason.

Allied Artists Pictures/Photofest

Siegel and Wanger convinced the warden that not hiring the ex-con would undermine their case for reform in the movie. In his autobiography, the director recalled Heinze agreeing, but with one condition: “Each day Gordon reports to work, he’ll be admitted through a side gate. Guards will strip and search him, both on entering and leaving.”

Throughout the shoot itself, the crisp and precise sounds picked up by recordist Paul Schmutz added immensely to audiences’ immersion in the inmates’ experience. As the narrative unfolds, layers of sound are gradually built over the constant resonant hum of the cell block, from cell door and bar clangs to machine noises, communications systems and loudspeakers, all woven together in the chaos of the major riot sequences.

For the exterior riot scenes, 700 volunteers out of Folsom’s 4,500 inmates were screened by the yard captain’s office and the convict-elected Inmate Council, and selected to participate as extras. None of the convicts could be shown in close ups — only actors, state police officers and prison guards serving as extras. The sequences were shot with armed guards on duty atop the walls.

Describing the shoot for Stuart Kaminsky’s 1974 biography, Don Siegel: Director, Brand said, “We didn’t know what…would happen in that prison yard during the riot scenes. Those were spooky scenes… You had to be there to capture what happened like you were in Vietnam in a documentary.”

Production wrapped on the 16th day, but the following week minor scenes were shot over two days at another location because “of a few cell interiors which presented difficult problems for us to light,” Siegel told Bogdanovich.

Allied Artists launched Riot’s release with a $350,000 promotional budget, unprecedented for the studio. The week of its opening, the bi-weekly general-interest magazine Look published a major feature story by producer Wanger, describing prison conditions and the complexity of reform explored in the film.

With his career re-established, Wanger produced Siegel’s classic Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) and ended his career with the disastrous production of Cleopatra (1963) that almost ruined 20th Century-Fox. Siegel became a major director, making Clint Eastwood an A-list star in Dirty Harry (1971) and taking him to another prison in Escape from Alcatraz (1979).

Seen today, with the exception of a few minor anachronisms, Riot in Cell Block 11 still speaks directly to our dysfunctional penitentiary system. The growing privatization of prisons, which raises America’s already highest rate of incarceration in the world, gives a new twist to the words of California corrections director Magee in the film’s opening newsreel montage about “the shortsighted neglect of our penal institutions amounting to almost criminal negligence.”