by Debra Kaufman

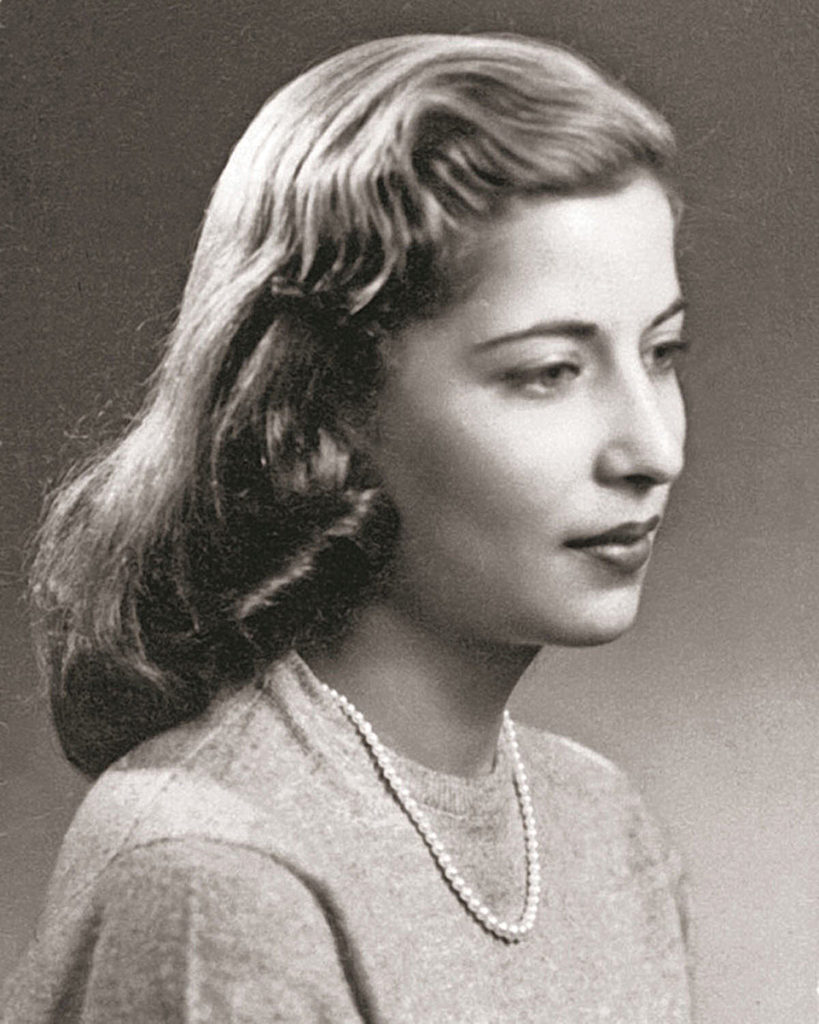

In a year that’s featured contentious debates over the #MeToo movement, On the Basis of Sex, which opens on Christmas Day, is the most timely holiday present imaginable. The Focus Features film, directed by Mimi Leder and edited by Michelle Tesoro, details the early career of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Felicity Jones), who has championed women’s rights throughout her lengthy career. She started off as one of only nine women in her Harvard Law School class of over 500, and the movie’s title refers to the first of Ginsburg’s many judicial battles for gender equality.

Coincidentally, two separate documentaries on Ginsberg were released earlier this year: RBG and Who Is the Notorious RBG?

CineMontage caught up with Tesoro to talk about her experiences working on this project, the challenges of transitioning from episodic TV (The Newsroom, 2012-2014, and House of Cards, 2013-2018, are just two of her credits) to feature films, and her love of editing.

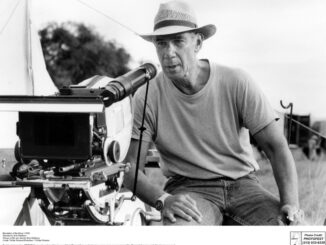

Tesoro first met director Leder on the last episode of HBO’s Luck (2011-12), a project about the world of horse racing. “Mimi and I did the finale together,” explains Tesoro. “She’s a really good director — very specific, which is a dream for an editor. She knows what she wants and is able to get it on set, but she leaves it open to interpretation.” Leder tried to bring Tesoro onto other projects since then, but the timing didn’t work out until this feature film.

“A high-pressure situation” is how Tesoro describes editing On the Basis of Sex. “It’s a biography, but we wanted it to be more than a straight biopic,” she explains. “Our first conversations were about making it cinematic.” According to the editor, the screenplay by Daniel Stiepleman touches on Ginsburg’s many struggles being a female lawyer in a male-dominated arena from her first days in law school, which meant that much had to be condensed.

“When Ruth interviews for a job after graduating law school, she goes from door to door and is turned down 12 times,” says Tesoro. “We had to condense that into one scene, in which she states that fact.” Noting that although On the Basis of Sex is a period piece, it still also feels modern, according to the editor. “Yes, we’re talking about a real person’s life, but we also wanted it to feel like today,” she adds. “It’s important for her to communicate to a younger generation about not taking your rights for granted.”

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Tesoro found Leder to be a dynamic director. “Mimi found a way to put her voice into it,” Tesoro says, explaining that she and Leder would have conversations during the shoot about the scenes, with the director describing how she shot each scene. “A good example is the scene where [Ginsberg’s husband] Marty Ginsburg [Armie Hammer] discusses Swedish tax law at a party, and then he’s looking for Ruth. The way the scene is written, it starts out from Marty’s point of view; for all intents and purposes, it’s Marty’s scene. Mimi covered that, but she also had all these shots from the points of view of Ruth, who wasn’t with the men’s or women’s circles at the party. Mimi and I talked about how we’d rather play that scene from Ruth’s perspective, which is what we did.”

The biggest challenge in cutting On the Basis of Sex was that, as a legal story, it required a lot of background information. “Mimi and I were aware during the shoot that we didn’t want it to be too expositional,” Tesoro offers. “You don’t want people to feel like they’re being told, but that they’re discovering it in the moment. When Mimi got more from the performances than was in the script, we were able to scrape out some of the exposition.

“One tricky scene was when Ruth meets plaintiff Charles Moritz [Christian Mulkey] for the first time in Denver,” she continues. “There is a scene with his mother doing the crossword puzzle. It was a great device, making you feel like you’re in a real moment, and you had something going on that was parallel with the exposition. Mimi and Daniel did a lot of work to keep a kind of personal touch and accessibility to the material.”

Tesoro confides that a few scenes resonated with her and Leder as women. “What’s interesting about this movie is that it’s completely from a female perspective,” she says. “In one scene, the lawyer/partner Greene [Tom Irwin], who is interviewing Ginsburg for a job, looks down at her boobs, and she looks up — and there’s this moment. The producer wasn’t sure the moment was landing at first but trusted our sensibility about it. Then we showed it in previews, and it really landed. I love that about the film; we need more of those scenes.”

Another sequence of which the editor is particularly proud is the ending, in which Ginsburg ascends the steps of the Supreme Court. “Mimi got this idea for this little epilogue, signifying Ruth’s transition to the Supreme Court,” says Tesoro. “I came across the audio for the cases she argued in front of that Court, and her words were like fire. I decided to surprise Mimi with those audio sound bites in the assembly — and they stuck.”

Tesoro hopes that audiences for the film learn more about Ginsburg and how one person can really make a difference. “I was privileged to grow up with certain rights that were assumed, and Ruth did not,” she says. “Yet she was able to effect a lot of change, with her own grit and with the support of her husband and the Ginsburg family. I want people to take away what she did, and feel grateful for it, as well as realize that they can be their own agent of change. The fact that she and Marty did it together shows that it’s all about equality. Equal rights for women mean equal rights for men.”

As a Filipina and a woman, Tesoro has often experienced being an anomaly in a largely white, male post-production environment. “Being the only woman has happened maybe half the time,” she says. “More often, I’m the only person of color there. Oftentimes, people have no idea what to expect when they meet me. On one TV show, my director was looking for me, and he looked right past me. That happens to me all the time. I always love the first moment of that person adjusting to the fact that I’m his editor — and then we get over it and move on.”

Tesoro gravitated to animation on TV as a child and in high school she went on to study photography, video and theatre production. Then she attended New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. “I went to school thinking I was going to be a cinematographer,” she recalls. “But as an undergrad, you can try all different jobs, and I quickly fell in love with the control and creativity in the editing room.”

Upon graduating NYU, Tesoro got a job right away at ABKCO Music & Records, a music publishing company. She started off as a video/film librarian and, three years later, was editing music promos. “I felt that even though it was a great job and I loved my co-workers, it wasn’t what I thought I’d be doing,” she admits. “New York City is a tight-knit community in terms of editing, and I was competing with very experienced people to cut shorts for free.”

Several Tisch friends had moved to Los Angeles and liked it, so she followed them in 2005. In addition to those friends, she had met editor Lora Hays, who introduced her to another editor, Paul Barnes, ACE. “I asked Paul about the ACE Internship Program and he introduced me to Marty Nicholson, who was a wealth of information,” she recounts. “He told me I had to get into the Editors Guild, and to become an assistant first.” She didn’t get into the program, but Nicholson encouraged her to attend the Internship Program applicants workshop — and to join the Guild.

“It was one of the first things I did in Los Angeles,” Tesoro explains. There, she met an assistant editor who told her that the pilot he was working on was looking for a post-production PA. She applied for the job but instead became post coordinator on the pilot, In Justice (2006). “It was a great position to see how everything worked,” she says. That show’s associate producer Keri Young and ABC/Touchstone post-production executive Bruce Sandzimier tapped her for another pilot, Just a Phase (2006), her first assistant editing job, for editor Mallory Gottlieb.

That pilot didn’t get picked up but it led to another assistant editing job on another pilot, David Manson’s Saved (2006), which went to series. “I did the series, and that’s where I met editors Peter Frank, Lisa Bromwell and Michael Ruscio, and worked with them for the next five or six years,” Tesoro relates, noting that, after Saved, she worked on Raines (2007) and then Swingtown (2008).

It was on the last series where Tesoro made the leap from assistant to editor. “I did the pilot with editor Ron Rosen; it was directed by Alan Poul, who was the director/showrunner,” she recalls. “When Ron left for another pilot, he told them that if they didn’t bump me up to editor, he’d take me with him.” Swingtown was also the show on which Tesoro met award-winning editor Sidney Wolinsky, ACE. “We became very good friends and worked on House of Cards together,” she says. “I now consider him my mentor. We always ask each other for advice. There is a lot of mutual respect and trust between us because we are both very honest with each other. You don’t get a lot of that in Hollywood.”

Tesoro considers HBO’s In Treatment (2008-2010) to be her breakthrough job. “It was the second show I did as an editor, and really it was the most impactful,” she attests. “I wouldn’t have gotten that job had Alan not bumped me up. Before I was bumped up on Swingtown, I had assisted on the first season of In Treatment and cut a little short for one of the producers, Rodrigo Garcia. The show moved production to New York City, but they kept the post-production in LA, and I was made an editor that season. Working on an HBO show gave me pedigree moving forward.”

Two full seasons on In Treatment led to another breakthrough when HBO senior programming executive Gina Balian put Tesoro’s resume in a large pile of applications going to director/executive producer Michael Mann. “For whatever reason, I got picked to work on his new show Luck,” the editor says. “I’d never worked on that level before. At the time, it was pretty intimidating; I was junior to everyone else, and my assistant and I were the only two women in editorial — although I was never uncomfortable being one of the only women.”

Tesoro worked on Luck for two seasons and, as mentioned above, met and worked with Leder on the show’s finale, which ultimately led to On the Basis of Sex, her fourth feature editing job. The others are Natural Selection (2011), for which she won SXSW’s Best Editing Award in the Narrative Feature Category; Revenge of the Green Dragons (2014); and Shot Caller (2017).

Having worked in television for most of her career, Tesoro says she feels she’s still transitioning into feature films. “I’m still trying to make that move, and it often feels very parallel, like I’m doing two different things at once,” she explains. “I still mostly get high-end TV series, and sometimes those credits don’t translate to features. People still question my feature experience, saying ‘You’ve done some great TV, but only a few features…’ I still feel like I have one foot in each pool.”

But whether it’s theatrical films or television, Tesoro thoroughly enjoys her profession. “There’s the intimacy of working with directors and trying to create something they have spent years developing,” she says. “They have an idea in their heads, and you’re doing it together. On every project, I learn a lot about the subject with this person who has a vision for it. And the editor is the last person to touch the film before anyone sees it.”

Her advice for up-and-coming editors, especially women of color, is to keep challenging themselves. “Be confident in yourself and what you have to offer,” Tesoro stresses. “You can’t hide what you are, so you might as well be really good at what you do and build a practice of integrity.”

The editor adds one more piece of advice: “Whenever my fellow female editor friends ask for advice on what to do in a situation, I often tell them, ‘Pretend you are a white, 27- year-old-male, and do what he would do.’ Basically, as long as you’ve got the goods to back it up, be entitled to what you want.”

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg would not disagree.