By Norman Hollyn

Alan Heim has edited many films that are, arguably, high on the list of innovative achievements in editing, among which are his collaborations with the late director/choreographer Bob Fosse – Lenny, Star 80, and All That Jazz (for which he won an Oscar). He has also helped to create memorable characters in films such as American History X, Hair, Valmont and Billy Bathgate as well as television shows Liza with a Z and Introducing Dorothy Dandridge.

He recently completed editing The Notebook, directed by Nick Cassevetes for New Line Productions, Inc. The film is framed by a story in which James Garner reads a love story from a notebook to Alzheimer’s victim Allie Nelson (Gena Rowlands). The love story recounts a fateful summer romance between Noah (Ryan Gosling), a local boy from the opposite side of the tracks, and young Allie (Rachel McAdams), the daughter of a very wealthy couple who come to North Carolina for a summer vacation. The parents break the romance off, but the young couple continues to love each other, even while being out of touch for years.

Norman Hollyn: You’ve worked on such a variety of films. What about this particular story interested you?

Allan Heim: I found the script to be very moving. I never cry when I read a script, but I found that I cried at two points while reading this one.

NH: Did those scenes continue to affect you in the same way after they were shot and during the editing?

AH: I actually sobbed during the dailies when Gena Rowlands recognizes the Jim Garner character for the first time, and I was very moved at the end of the film, though I don’t think I actually cried at the dailies. Gena and Jim’s performances were just stunning.

NH: Did you end up cutting out much of the script?

AH: The first cut of the movie was over three hours long. Then Nick came in and we started recutting from the top. The next thing we knew, we were at an hour and forty-eight minutes, and the film was not playing well.

What happened in the process, we had dropped one of the characters – a love interest for Noah. That other woman was absolutely splendid but, in the interest of time, we had gutted that performance. So we decided that we should put back part of her scenes. These are decisions you can’t make when you’re shooting. You won’t know what should stay and what should go until you actually put each scene in context with the others.

“When you’re editing, you’re manipulating not only the material, you’re manipulating the audience” – Allan Heim

[Noah and Allie have just gone to an empty house where they tenuously begin to take off their clothes. Suddenly, one of Noah’s friends bursts in to tell them that Allie’s father has called the police and everyone is out looking for her. The two lovers quickly return to Allie’s house, where the police and her family are waiting.]

AH: The top of this scene took awhile to get going, so we took a lot of things out. As she runs up the house, we hung a bit on Noah walking up the house. When he enters, we were able to play just a little bit of dialogue from the family while we were looking at him. Much of the original dialogue turned out to be unnecessary. At this point, we just wanted to keep things moving. We wanted to get to the next step.

[Noah wants to take the blame himself, but the father (James Marsden) won’t let him talk. He sends Allie and his wife (Joan Allen) into his study and then asks Noah to wait for him. Noah walks into the waiting area by himself and, slowly, sits while we hear the muffled argument from the next room. We cut into a close-up of Noah.]

NH: This sets up the dynamics for the rest of the first half of this sequence – Noah waits in the outer room listening to the fight in the study between Allie and her parents.

AH: This size shot of Noah was the only one we had. He has this strange look on his face; he almost looks pleased. But what it really is, I think, is nervousness and a little embarrassment. Staying this long on him focuses your attention on him so we realize that his life is about to change in a big way. He’s beginning to make decisions, for the first time, based on what kind of person he is going to become.

[Inside the study, both Allie and her mother are standing in front of her father’s desk yelling at each other.]

AH: Hanging on Noah in the outer room enabled us to get the father into his seated position without walking him across the room. There was a lot of action that took place to get everyone into position. By focusing the scene on Noah, we were able to jump the rest of them all around the room with no matching problems.

NH: We’ve spent an enormous amount of time in this movie so far with Allie, but there are no singles of her at all.

AH: This is because Joan Allen is so good. When you have an actress like Joan Allen you sometimes want to say, “God, do I have to cut to somebody else?” And Allie, while quite wonderful in this film, is only reacting to her mother’s tirade. The only reason I want to go to somebody else is if they’re really delivering something that I don’t know.

[Allie’s mother yells that Noah is “trash, trash, trash,” and then there is a cut back outside to Noah listening.]

AH: We feel he is reacting to what Joan Allen has just said. We were also able to take a lot of dialogue out here, because we were cutting outside to Noah. This shot of his is an odd angle – looking at his back. But he turns, we see his face, and it’s a very strong contrast to the lightness he had when we last saw him.

NH: How did you decide where to cut back and forth from the argument to Noah?

AH: First, I cut the entire scene in the study without any cutaways to Noah. Then, the two questions were – where do you put Noah? And then – what do you get rid of? Each instance was different, but we were always looking to have the boy react to what was going on inside the study – What does he hear?

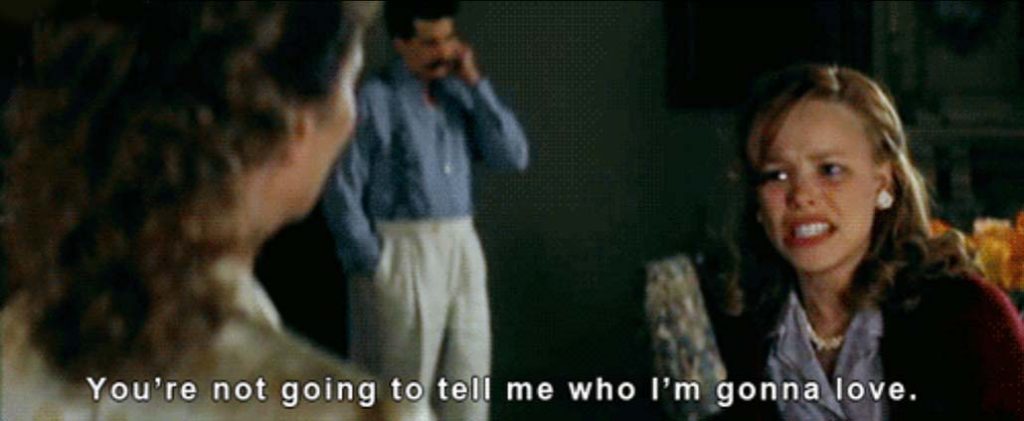

[We cut back inside to the study to find Allie’s mother still berating her. Then, Allie breaks away from her mother, furiously telling her that she can’t tell her what to do.]

NH: This is the first time that we come around to the daughter in close-up.

AH: Allie is acting here, as opposed to reacting, so we want to see what she is thinking and feeling. Note that we’ve jumped the dad across the room while we were outside with Noah. Once again, by cutting outside and back, we were able to lose a lot of what is sometimes called “shoe leather,” people walking around.

She hopes that her dad will see her point of view. But, instead, he says that she’s too young. Now, even though the father has said that in a very low voice, we go outside again on this line and we take a certain dramatic license here. We go to Noah reacting to the line, even though it’s really too low for him to hear. It’s the magic of film that makes you feel that he’s heard it.

NH: Noah stands up and leaves. Now you cut back into the study for more of the argument. But Allie is about to run out and catch him for their scene outside. Did you have to adjust the timing of the argument to make the time span plausible?

AH: We took out an enormous amount of dialogue, all in the interest of keeping the story flowing and getting Allie and Nick outside in a reasonable amount of time. There was another factor that Nick and I would talk about. How much abuse should Noah listen to when he’s sitting out in the room? Would you sit in a room and listen to people who don’t like you very much, vilify you for 10 minutes? I don’t think so.

[Outside, we immediately get into tight over-the-shoulder shots between the two of them.]

AH: We chose to go into tight shots for the performance and to accentuate the moment between them even though using overs makes it tougher to cut, since you’re always struggling against mismatched actions on both characters. I’ve worked with some really fine older actors and actresses, and they match action really well.

Later in the film, Jim Garner pulls out an envelope. He does that action at about the same word of dialogue on every take. Younger actors don’t do that as much. But, if you overlap a word, you can take most of the curse off a mismatched head. If you find a hand movement, you can deflect the audience’s eyes – actually any type of movement. The important thing in a scene like this is to keep the eye contact between the two people.

[The dialogue between them comes right on top of each other’s. Then, she asks him to come back to New York with her. He tells her that he can’t. “What would I do?”]

NH: Now you slow the pace way down.

AH: This is just a heartbreaking line and we wanted to accentuate it. We probably could have lost 10 to 15 seconds here, but it wouldn’t be the right thing to do. In many places in this movie I cut right on the action, right on the word. But this is not a place where you want to do that.

[Noah turns and walks away from Allie and we hold on his back. She runs to him and starts hitting him.]

“These are decisions you can’t make when you’re shooting. You won’t know what should stay and what should go until you actually put each scene in context with the others.” – Allan Heim

AH: There are about five takes of the action when she pushes him against the car. And in one of the takes, he did something completely surprising – he began to slap himself. Of course, we put it in and it’s never changed. It was fascinating – it raised all sorts of questions about how Noah got to that point emotionally.

[He jumps into the truck and then we finally cut to Allie through the truck window.]

AH: This seemed to be the place to go to her. She does a wonderful thing there. She goes from this real rage, and suddenly she thinks to herself, “Oh, what have I done?” It’s a really good performance as the truck begins to pull out.

[The car pulls away from here and we end the scene as she watches its taillights disappear.]

AH: There was no reason to stay with the truck any more than we did. It was just enough to let us feel what she’s feeling.

NH: Some have said that there are two different approaches to editing. One is to be very conscious of every single cut and where and why you make them. The second approach is to cut from the gut. Of course, that’s an artificial distinction, but do you fall in one camp or another?

AH: For me, it’s a mixture of the two. When you’re editing, you’re manipulating not only the material, you’re manipulating the audience – you’re moving them from place to place. You want the audience to comprehend what it is you’re doing, to know why you’re cutting to Noah or Allie at a particular point. But you don’t want them thinking about it every minute. You just want it to seem natural “I want to see her. I want to see what she’s doing at this point.” That ‘s what must guide the cutting. And that’s really a combination of the head and the gut.