By Rob Feld

Allyson Johnson remembers finding the work of director Claude Chabrol while taking film classes at SUNY Purchase, where she was a music major studying clarinet performance. She had grown up going to Woody Allen movies the day they opened with her family, but it was a scene from Claude Chabrol’s “Les Bonnes Femmes” that made her discover the creative potential of film editing. The sound of children playing in the distance can heard as two lovers walk and kiss in the forest, but the ensuing edits trick the audience into believing they are making love when in fact he is strangling her.

“The film was made in the 60’s, so no sex or violence could be shown on screen,” Johnson recalled. “Just the faces of the lovers and perfectly placed cutaways to elements of their surroundings. It was chilling. I will never forget the shock and amazement at how the audience could be manipulated in that way. I was hooked.”

Johnson adopted the I’ll-do-anything approach when she graduated and landed a job as a receptionist—by her own account, a poor one—at a commercial production company, then as a PA at cable startup A&E (né ARTS). To leap from writing, producing, and editing promos to longer form, she learned the new AVID system, which gave her opportunities in documentary and eventually editing “The Who’s Tommy: The Amazing Journey” for Barry Alexander Brown, who directed it, and garnering an Emmy nomination for herself. To make the move to narrative film, Johnson then served as Brown’s apprentice when he cut Spike Lee’s “He’s Got Game” and “Summer of Sam,” after which she would never assist again and would collaborate repeatedly with Mira Nair.

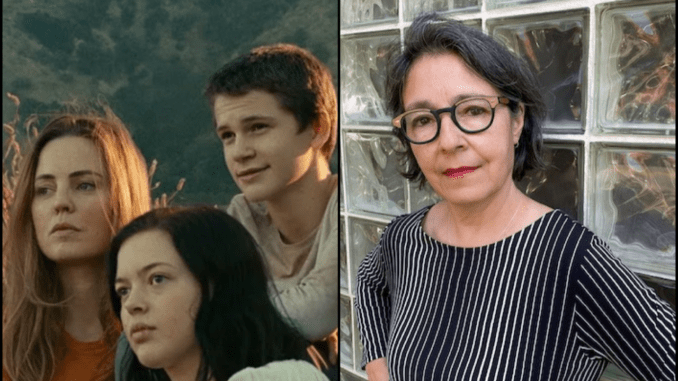

Johnson recently cut two episodes of Apple TV+’s seven episode “The Mosquito Coast,” which is based on Paul Theroux’s best-selling novel. The drama follows the adventures of the Fox family, who live off the grid on California farmland. As their father, radical idealist and inventor Allie Fox (Justin Theroux), feels the federal government closing in on them because of a past incident, he takes his family on the run, through mountains and desert, toward an imagined safety on Mexico’s Mosquito Coast. The variety of tones and textures seem designed to keep an editor on her toes.

“Allyson is an extraordinary film editor with the most marvelous sense of musical rhythm that permeates her entire process of cutting and shaping motion picture,” says Nair, who first worked with Johnson on “Monsoon Wedding.” “Her steady and calm exterior belies the unexpected waves she can sculpt within the film at hand. There is no one genre or style Allyson is daunted by. Sure of herself in the most self-effacing way, Allyson does what only the best can do: Weave a tapestry of wonder, with great economy, in an original non-imitative style, to propel us through stories of any language in the world.”

Johnson explained her craft in an interview that was edited for length and clarity:

CineMontage: Not everyone gets one these days, but did you have an apprenticeship experience?

Allyson Johnson: Barry Alexander Brown is my mentor. In those days, Spike Lee was still cutting on film, which was great for me because I was able to learn how to cut on the Steenbeck before the film business went completely digital. A film cutting room is a great learning experience because you, as an assistant, are in the room with the director and editor when they are working. You get to hear the conversations and see the process. It was priceless, as was working as Barry’s editor on “Tommy.” Although he was an accomplished editor himself, he was very good about being hands-off in the cutting room. He gave me the space to do my thing but taught me so, so much. The “Tommy” documentary was a perfect vehicle for non-linear storytelling and Barry is the king of non-linear story telling. We had performances and interviews spanning 25 years, the Ken Russel film “Tommy,” and the musical that had just hit Broadway. Intercutting all of these moments, going back and forth in time, and keeping the story of “Tommy” and the journey of the rock opera itself going simultaneously was so refreshing.

Tell me more about that technology shift from film to digital. Do you feel we lost anything?

Johnson: I had been editing on linear tape-based systems then moved to Avid while it was beta testing in New York. But I found that even though the business was going in the direction of non-linear systems like Avid and Lightworks, it was a slow shift. Many directors and editors didn’t want to make the change, so I had to learn how to cut on film after I learned the Avid. I’m so glad I was able to experience editing on film. I think the biggest loss when switching to digital was that, because it’s a much faster process, you don’t get to live with the material. You would think that faster equipment would mean you had more time to think and finesse but instead you find yourself with less time because the schedules are shortened and you’re also doing rough music and rough sound effects, which in the film days was not done by the picture department. Also, not being able to project a film on the big screen to see how things are flowing is a real problem. Things play differently on phones, iPads and big screen TVs than they do in a theatre. These days we have to keep all that in mind but always think about what platform the film was ultimately intended for.

You have such a broad experience of genre and director style: dream-like Mira Nair, Spike Lee, broad comedy; what sort of preproduction discussions do you like to have to understand visions?

Johnson: I don’t usually get to have pre-production discussions but when I meet a director for the first time, it’s helpful to find out what films they like, what directors they gravitate to, and if there are any examples of scenes or films where the editing stands out in a good way to them. My feeling is that my job is to put the vision of the director on the screen. When it’s a new editor/director relationship, it takes some time to learn the director’s style and to develop that unspoken language that is so great when you are working with a director you have a long-standing relationship with. With directors like Mira Nair and Spike Lee, the footage that you receive has their vision baked into it, so the editor needs to listen to the footage. Knowing the vision of the director is important to the film obviously but knowing how the director likes to work with his or her editor is essential in order to balance work and family life.

What do you need from a director on a television series like “Mosquito Coast,” where you are responsible for certain episodes, as opposed to a feature film? Do your processes differ at all?

Johnson: Television series and features are different creatures because TV has the addition of the showrunner added to the mix. I think there used to be more of a difference but these days I almost feel like I’m editing an 8-hour movie instead of eight episodes of television. There’s nothing better than a director who sends notes explaining what they meant by what was shot that day. I do miss the days of watching dailies with the director every night. There was much less second-guessing going on in those days. Unfortunately, that rarely happens. The schedules are so tight that the directors rarely even have time to sleep.

On a TV series, you always have to be aware of the “vision” of the series as a whole. You can’t just think about the director’s vision because the show runner’s vision is the one we all have to work toward. The first season of a series can be challenging in that way because everyone is new; cast, director, show runner, editors. Hopefully after the first few episodes are in the can we can all relax into a rhythm. In “Mosquito Coast,” each episode is very different from the one before and after. The locations dramatically change as do the situations the family finds itself in. In this way it is different from most episodic television. Each episode had a very different feel to it but all the editors had to make sure to keep in mind what happened in the previous episode and what was coming in future episodes. It’s a great experience because it is a mix of thriller, adventure, drama, and comedy. It keeps you on your toes as an editor and as a viewer. Never a dull moment.

Neil Cross’s scripts were so rich with mystery and layers of story lines that when we were bringing the episodes to time, we ended up repurposing some scenes because we had lost an entire character but still needed the events surrounding the character for the rest of the episode. For instance, in episode 104 the characters keep hearing noises from the pipes in the old house. Allie walks around the halls listening to them, the kids hear the noises in the middle of the night, etc. These noises are directly related to another story line that is no longer in the show. But the noises themselves became a character in the episode that is a motivation for the other characters.

What did the production process look like for you?

Johnson: Our normal process was slightly altered because the pandemic hit right smack in the middle of production. We all had to learn a new way of working very quickly. The remote work systems had a lot of challenges in the beginning but since we already had most of the episode in the can and Neil Cross, the creator, was working from New Zealand, we ended up using local systems for the first few months. We luckily didn’t have to deal with the remote system issues until much later in the process. I would wake up to notes every morning and when Neil woke up, he would have the changes ready to look at and then we would FaceTime and discuss what was working and what wasn’t. We had daily Zoom check-ins with the post crew, which was essential. We did sound, music, and visual effects spotting sessions virtually and the editors were sent mixes to review before the final mix day. This is all standard at this point but new to us back then.

How does your emphasis change between genres?

Johnson: I think you definitely need to be in a slightly different head for different genres. Editing is always about timing and story but generally I find comedies to be cut much faster (almost like an action film). Musicals are trying to do a lot of things at the same time and sometimes story can get in the way of a fabulous dance number, so the balance is crucial. You don’t want to cover a great dance move or beautiful vocal to drive home the story, so you’re always looking for that moment to slip in a cutaway or a line of dialogue that won’t derail the flow of the song or dance number. I’m thrilled that I’ve been able to work in so many different genres. I love the variety. My music background has allowed me to cut some great music shows like “SMASH” and “The Get Down.” My feeling is that editing a scene is like composing a piece of music. The dialogue, sound effects, and what’s happening visually are each a different instrument in the composition and the placement of each picture cut, sound effect, head movement, or eye blink is what will make or break the scene.