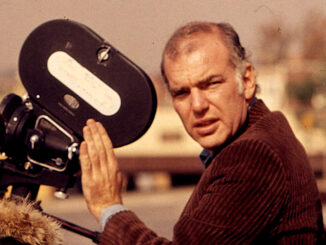

by Scott Essman

Mark Goldblatt, President of the American Cinema Editors, has been cutting feature films for 23 years. His credits include both Terminator films, Starship Troopers, Armageddon, and the upcoming Paul Verhoeven thriller, Hollow Man. In this interview, he reflects on some of the enduring challenges that editors have always faced and discusses some newer issues, as well.

The Editor’s Relationship with the Director

Mark Goldblatt: It is a critical relationship on several levels. In terms of the work itself, it’s always a good idea to collaborate with people who complement each other. For an editor — the director’s right hand in the final process of making a film — this collaboration is a crucial thing. For maximum success, it’s always great to hook up with a director who relates to you personally and aesthetically. Directors want to feel secure that their movie is in reliable creative hands. Sometimes the best collaborations of this sort involve a kind of psychic relationship where the editor may anticipate the director’s needs before the director actually articulates them — in terms of a cut, the direction of a scene, or a suggestion based on dailies.

Ultimately, the editor offers the director an objective point of view of the material and hopefully innovative ways of making it all go together. However, you have to both be talking the same language — making the same picture. With the director, you are dealing with a creative individual who brings a specific vision to the table. On the other hand, if you perceive a way that the material can be maximized, you need to present that. Disagreements may be part of this collaborative process. Luckily, with the Avid or Lightworks, we can try many different approaches to the material and compare them to see which works best.

Objectivity & Versions

MG: I believe in instinctual gut response editing — sometimes the initial response is the best response (but certainly not always!). As an editor, you may be more objective than the director, who has the baggage of having made the shot in the first place — the struggle to get the light, camera move, and performance all in one take. As an editor, the issue is not how long it may have taken to make a specific (or difficult) shot or scene, but what’s working best for the overall motion picture.

“Cuts create rhythm, which is a musical concept.” – Mark Goldblatt

Ever since the advent of the flatbed, we have tended to review our cuts a lot more often then we did on Moviolas. With digital, we now often retain myriad alternate cuts of scenes. Constant reviewing and intellectualizing of edits sometimes clouds one’s sense of objectivity. In the past, there wasn’t generally as much footage shot as today, so there often weren’t as many variations and possibilities in terms of editing. The greatest challenge for the editor today is to keep a sense of objectivity when looking at your material.

Editing by Committee

MG: The fact is, in today’s post-production environment, editors often find themselves in a curious position. Depending on the filmmaker’s clout, there may be a lot of outside notes and opinions about a scene; perhaps even strong pressure to take the film in a different editorial direction than the filmmaker intended. Does this ultimately produce a better motion picture? Not necessarily. I am of the school where I believe in the sovereignty of the filmmaker as artist, where the director is captain of the creative ship.

We know that film is an extremely collaborative art, and that commercial cinema is also a very high stakes business, and that many individuals bring a great deal of creativity and insight to the table. But I believe that all these contributions must ultimately be filtered through the director (with the editor’s help, of course) who has a precise vision of the material and the project. Generally, I have found that the most enduring works are the ones that reflect the vision of a single creative entity. Obviously, there is a collaborative concept within this, but I don’t think you want to have twenty people vote on every cut and every moment.

“In terms of the work itself, it’s always a good idea to collaborate with people who complement each other. For an editor — the director’s right hand in the final process of making a film” – Mark Goldblatt

Rhythm

MG: Cuts create rhythm, which is a musical concept. In this sense, editing is very much like a musical language. When you turn a scene over to a composer, they may well compose their music based on rhythms that you helped establish. When we add temp effects and temp music, it helps us explore potential directions towards the ultimate music and sound design of the motion picture.

New Tools

MG: We can’t be afraid of tools that take us into new terrain. The problem is that, traditionally, tools are capable of being misused. I believe that you have to embrace change and new technologies. As some sage once said, “The only constant is change.” You have to be willing to ride that current; otherwise, you set yourself up for great disappointment.

The Future

MG: The reality is that we are doing things in the editing room that we never did before. Editors’ creative imprint on the final work is getting much more precise on many levels. I have worked on a number of visual effects movies, and I have perceived a quantum leap in our degree of involvement in this process over the last few years. New media outlets are continuously popping up. The Internet is still in its infancy, with innovative audio-visual materials starting to be channeled through it. This means more opportunities for people who work in post-production. Just think of all the possibilities. It is an exciting time to be an editor.