by Edward Landler

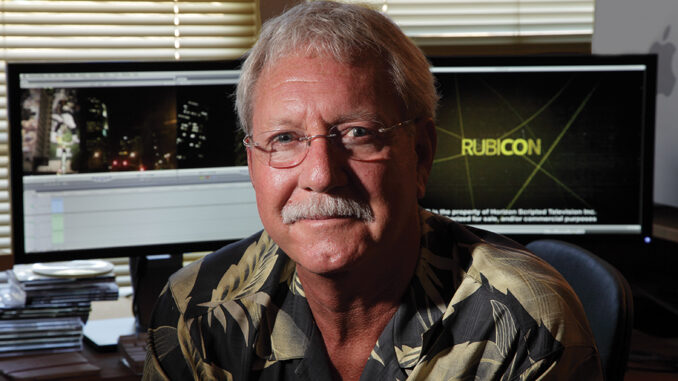

“Bring the work back into the cutting room” is the mantra of Terry Kelley, A.C.E. To save both money and time producing television shows and movies, picture editor Kelley has established a new workflow procedure that has proven successful on two television series—Showtime’s Brotherhood (2006-2008) and the conspiracy thriller Rubicon, which just finished its first season on AMC.

Kelley devised his approach from the most current advances in digital video technology. These advances have made it possible for anyone to make his or her own movies using just a digital video camera and a personal computer. With an inexpensive editing program like Final Cut Pro, anyone can plug the camera into the computer, capture the footage onto a hard drive, organize and edit it, add effects and titles, and output a finished product to a digital file that can be loaded onto the Internet or burned to a DVD.

If vast amounts of uncompressed high-definition (HD) image data could be efficiently transferred and stored in the hard drives serving TV and movie productions’ editing bays, Kelley reasoned, then the greater part of the editing workflow could be performed effectively in the cut- ting room itself.

“Instead of paying outside vendors, why not have union assistants do the same work better and cheaper?” says Kelley. “Why use telecine labs and online bays when the work can be done more accurately and efficiently by the assistant editor in the cutting room?”

Kelley wanted to bring back into the cutting room two key functions being completed in post-production houses: the syncing of dailies and online editing. He chose FCP as the editing software for the cutting room because of the adapt- ability it offers at relatively low cost.

Instead of sending raw dailies to be both transferred and synced in the telecine lab, as is standard procedure, telecine would now only transfer the footage to HDCAM masters MOS. After capturing the MOS tapes at low resolution in the cutting room, the assistant editor would sync them with the production audio.

For every hour of dailies, the post house telecine operator takes another two-to-three hours to sync sound. Apart from the operator’s $350-an-hour-charge, post house workloads could cause scheduling delays when syncing is figured into the transfer. When the assistant editor syncs up in the cutting room, the production avoids those costly delays and saves the production up to $1,000 a day or more, depending on the amount of footage shot. The assistant saves further time and money since he or she is more familiar with the material.

With Kelley’s workflow, the online editing is kept in the cutting room, too. Instead of paying $500 an hour for online bay rentals and more for tape stock and handling fees, the offline low-resolution sequences are redigitized at full, uncompressed HDCAM format. On a cable TV series, the savings on online editing range from $5,000-$10,000 per episode. Without spending on telecine, $100,000- $200,000 could be saved on an entire series.

When Kelley was brought on to Rubicon early this year as one of the two main editors, along with David Ray, he pitched his workflow concept to the producers, but initially found strong resistance.

“I was 100 percent skeptical,” says Rubicon associate producer Leslie Jacobowitz. “I had always used Avid. I never heard of using Final Cut Pro on a scripted TV show. I thought Final Cut Pro was for laypeople and small independent films—for things you see on YouTube.” But Rubicon executive producer Henry Bromell strongly supported Kelley’s proposal. As executive producer of Brotherhood, he had allowed Kelley to pioneer the new workflow procedure. They reviewed the proven economy of the editor’s workflow point by point, including the considerable initial cost that buying Final Cut Pro for the show, instead of an Avid, would save.

Jacobowitz accepted Kelley’s work- flow but she still had doubts, since Brotherhood was shot on HDCAM tape and Rubicon would be shot on 35mm.

Shooting for Rubicon began March 20 and the editing crew was in place from the beginning. Three assistant editors were brought in—Jen Lame to work directly with Kelley, Jennifer Davidoff Cook to work with Ray, and Shon Hedges to work the critical functions of the new workflow—syncing the dailies and doing the online. Kelley, Lame and Hedges were all fluent with the Final Cut Pro and Ray and Davidoff Cook quickly gained familiarity with the system.

The production stored all its image data on Final Cut systems, each configured with eight terabytes of high-speed hard drive space. Thus, each system had enough storage to keep all the low-resolution HD image data for every episode.

The dailies were captured to ProRes Proxy, a new codec from Apple that allowed for offline editing in full 1080p 23.98 HD at very small file sizes. Edited sequences could be transferred from one machine to another in seconds over the gigabit Ethernet, and all the media would remain online. This made it possible to avoid renting or purchasing a cost- ly shared-storage server like the Avid Unity or Apple’s Xsan.

“There was no shared storage,” Jacobowitz says. “With eight terabytes each, there were enough places for all of our material and, with a really organized system, we never had any footage offline or had trouble finding anything.”

In addition, Hedges’ editing bay was configured with eight terabytes of Serial Attached SCSI (SAS), a relatively new piece of technology with enough speed to handle uncompressed HD for the onlines. Priced at $3,200, the G-Speed eSPRO developed by G-Technology was the SAS connected hard drive array that enabled the Rubicon crew to capture each show to uncompressed HD, saving more time and economizing in transfer and online costs. All the uncompressed material was then available in the cutting room for almost immediate access.

“After the first online session, I could see it was working smoothly,” says Jacobowitz. “We saved time syncing our own dailies and conforming our own onlines. We had so much more control over what was going on in the post process––and we didn’t have to rely on a post house as much. We could get right into it without waiting. It also helped us work more closely together as a team.”

Assistant editor Hedges notes that the editing crew developed a rhythm in the workflow as the material for an episode moved with a sure pace from capture and sync to editing scenes to online. “The workflow allowed us to work together as a unit,” he says.

Doing the online edit in the cutting room, Hedges could also clean up technical details immediately without putting the material through another procedure requiring transfer to another location. In one episode, he removed lead actor James Badge Dale’s tattoo from a shot— a detail that might not have been recognized at all had the show been farmed out other hand, that compromises certain camera moves. When you’re making a movie like this one, for not a lot of money, you have to shoot fast. It requires a certain amount of cutting, but I’m happy to let things play as humanly possible, if there’s a rea- son to stay on the characters. But often the audience expects to see a privileged view of what they deem essential at any given moment, so it makes staying on shots a little harder than it used to be.”

The element Rosemblum likes best about romantic come- dies is the surprise. “The best romantic comedies are always real in their emotional makeup,” he says. “At its heart, Love and Other Drugs is a funny love story. What we all want is for our partner to look into our eyes and say, ‘I don’t care what your problems are––I am there for you.’”