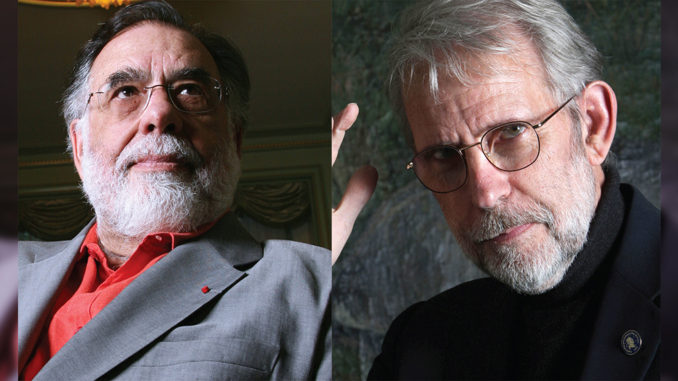

by Bill Desowitz • portraits by Franco Origlia/Getty Images

Youth Without Youth not only marks director Francis Ford Coppola’s first film in 10 years, but also signals a return to the personal kind of filmmaking that he prefers. Self-financed and shot in Romania, the highly philosophical film also reunites Coppola with his longtime friend and collaborator, Walter Murch, MPSE, ACE, CAS, the acclaimed picture and sound editor/re-recording mixer.

The filmmakers, of course, go all the way back to their pioneering American Zoetrope days in San Francisco, when Murch first did sound montage on The Rain People (1969) before becoming a sound editor on The Conversation (1974), and then both a picture and sound editor on Apocalypse Now (1979).

In fact, Apocalypse Now was the last feature Coppola and Murch collaborated on together––not counting the pinch-hitting the editor did on The Godfather: Part III (1990) and their brief reunion on Apocalypse Now Redux (2001). Murch suggests that working with Coppola is like going on an adventure into unknown territory: “And if you know this going in, then you jump on board willingly, as I did, knowing that there are still questions unresolved, but that is part of the adventure and excitement of working with Francis.”

Not surprisingly, Youth Without Youth was tailor-made for Coppola and Murch, with its ruminations on time and consciousness and the origin of language. Set primarily in Romania and Switzerland between 1938 and 1969, the fantasy/love story concerns a lonely old linguistics professor, Dominic (played by Tim Roth), who is desperate to complete a book that answers the meaning of life. Then, when he’s literally struck by lightning and miraculously survives, Dominic is transformed into a younger man with a superhuman brain. With this second chance to complete his study, however, he is immediately hunted by the Nazis and then falls in love with a mysterious woman who holds the key to his past, present and future.

Oddly enough, Youth Without Youth began as an outgrowth of Megalopolis, Coppola’s aborted epic project about New York post-9/11. He was having some difficulty with concepts of time and consciousness and sought the advice of a friend from high school, Wendy Doniger, currently professor of South Asian Studies at the University of Chicago. Doniger led him to the novella, Youth Without Youth, written by her mentor, Mircea Eliade, a renowned historian of comparative religion. The story instantly touched Coppola, who closely identified with the creatively unfulfilled protagonist. After all, even though the director had branched out with his lucrative winery in Napa Valley, California, he hadn’t made a film since The Rainmaker in 1997.

So Coppola embarked on a cinematic adventure that harkened back to his Zoetrope roots with Murch. He began shooting in October 2005 and production lasted 85 days with a predominantly Romanian cast and crew. He kept everything simple and low budget, inviting Murch to join the adventure at the first available opportunity. CineMontage recently spoke to Coppola and Murch in separate interviews.

Francis Ford Coppola

Cinemontage: What was it like to return to directing after a 10-year absence?

Francis Ford Coppola: I wanted to do something along the lines of what I had dreamed when I was 18––which was to make personal, avant-garde films such as the ones that inspired my generation: the Italians, the French, Kurosawa, Bergman…

So Youth Without Youth was an interesting opportunity, after plugging away at a big, personal movie, Megalopolis, and trying so hard at it. For many reasons that came up, I couldn’t do it. I used to say, “It’s like being in love with a woman who doesn’t want you.” And the problem with that is she may not love you, but you don’t have anyone else either. In the research of Megalopolis, there was a lot in that script about consciousness: What is existence?

CM: So it was similar to the way George Lucas plugged away at Apocalypse Now, decided he couldn’t do it and handed it over to you to direct when he decided to make Star Wars instead?

FFC: Exactly. I sort of ran away with this Romanian hussy and was following in the footsteps of Eliade, a man I had enormous respect for. I was looking for how to best express the phenomenon of human consciousness because I knew everything comes out of our concept of time. Time isn’t really real, other than how we can conceive it. Fortunately, I was doing well with my winery, so I could finance the film. I went off to Romania and didn’t tell anyone. It was like a secret affair and I didn’t even tell my wife that I was writing this script. That empowered me in some ways. So I went on this [adventure] and became the same kind of filmmaker as when I made The Rain People; I put all the equipment in a truck, didn’t tell anyone and just did it.

“I wanted it to be a love story wrapped in a mystery about the nature of language.” – Francis Ford Coppola

CM: At what point did Walter Murch become involved?

FFC: Walter became involved after I shot it. Walter is such a desired and sought-after editor––if you’re not on his schedule––and I always try to work with him. When I heard he was finishing Jarhead and that there was a chance he would become available, I got in touch with Walter and gave him the script and invited him to come to Romania.

Ultimately, he said yeah. But I already had an editor, Corina Stavila. She did many good things, but Walter is so multi-dimensional. As an editor, he is a true collaborator and a sound genius. It was a thrill to work with him again. And now that I’m on his schedule, he’s working on my new film in Argentina, Tetro. It’s such a comfort to have him. You get so many opinions: Am I going right? Am I going wrong? But it’s better to get a few opinions from people you can really trust.

CM: What was one of the important contributions that he made?

FFC: His idea for the opening was originally different from what we ultimately did, but it was to begin in this old professor’s dream and then he wakes up and he’s forlorn. I’m sort of touched by some old guy who gets up and grieves because he’s alone. I bet there are millions of people out there who have come to that: They missed the boat––and the woman or man that they love––and they’re just alone.

CM: Why did you shoot the film in such a classical style?

FFC: Knowing that the film had this fairytale story, I knew philosophically that it was very rich, so I wanted it to be stable and clear in storytelling, with only an occasional reference to this long lost love. So I deliberately stayed away from a woozy style movie. I thought it would be better to tell the story clearly in three sections: the discovery of the man, when he’s on the run, and when he meets this woman and it becomes a love story. Very classical, with the feeling of movies from the ‘30s.

I think so much in movies has become a brainwashing of the audience, where the story has to be linear and all the points have to be resolved or add up at the end. But in the end, when I had to digest it with Walter’s collaboration, I wanted it to be a love story wrapped in a mystery about the nature of language, consciousness and existence––just for the fun of it.

A lot of times people say, “This movie was totally over my head.” Well, not really. It was like a Twilight Zone story. You don’t have to grasp it all. Forgive me, but Hamlet is just a kind of murder mystery. There’s more to it than that, once you’re drawn into it. I’m thrilled if people want to see Youth Without Youth again, but not because they need to see it again to understand it. There’s more to get out of it and I think some of it is profound, but I can’t claim to have these profound thoughts because those come from the author

Walter Murch

CineMontage: Given your deep philosophical interests, you must’ve been thrilled when Francis Coppola asked you to collaborate on Youth Without Youth.

Walter Murch: Right. It immediately resonated on the level of things I’m interested in. But, clearly, I needed to know how we were going to do this. It was a challenge because Eliade was an academic and most of what he wrote were books and papers on the history of comparative religion. As a relief from that, he would write these novellas, which covered the same sort of territory. But he was freed from the constraints of academia. Nonetheless, you can tell that philosophical furniture is being pushed around when you read the novella, and the characters are there to convey these ideas more than existing as living, breathing characters.

“I had much more latitude in the ability to recompose within the frame with digital acquisition because you’re not dealing with a grain structure. So we found that we could move the image around and play with it cinematically in ways that would have been quite cumbersome [and limiting] in film.” – Walter Murch

CM: So the first step was obviously to make it cinematic.

WM: Yes, and it fits in with Francis as I’ve known him for 40 years. The projects are: “Let’s go and explore unknown territory and who knows what we’ll find?” So he’s a filmmaker very much in the adventure mold––somebody who’s interested in the process and finding out what the process will turn up, rather than somebody who wants to take a vacation in Seattle and exactly maps out the route that he will take. There’s a high level of serendipitous discovery going to be made through the process of making the film.

CM: And what was this particular adventure like?

WM: Well, on one level, it felt extremely familiar because Francis is one of those people who you meet in life with which you have both a professional and personal relationship over the years. I can pick up a conversation with Francis that we were having two and a half years ago.

CM: There are a lot of references to films of the past––the Citizen Kane-like opening, as well as The Third Man and Apocalypse Now. Was there much discussion about this beforehand?

WM: We didn’t talk about it overtly. But, again, it’s at that level where we both know what we’re doing because we have such a long history together and there are things that are just understood without necessarily going into words.

CM: What were some of the basic challenges presented to you on Youth Without Youth?

WM: On the simplest level, the film was already assembled by the time I joined the project. So there was a little bit of a cart-before-the-horse situation, where I saw the assembly put together by Francis and Corina Stavila. This was arranged in advance, so there was no question or bad feeling of me usurping someone else’s work. But I hadn’t yet seen the dailies [which eventually took six weeks] and I was looking at a cut that was just under three hours long. And we knew that we had to reach a goal of two hours.

So there were some of the usual kinds of questions, such as, “Here are the ideas that we want to get across; is this one pulling its weight, or should we concentrate more on something else?” For example, there was a whole subplot that was developed and shot, which was in the novella, about student radicals in Romania in 1938 and the Secret Police thinking that Dominic was somehow linked to them. But in the interest of setting up the personal side of the story early on, I suggested that we drop it.

CM: What about reworking the opening?

WM: That nightmare opening, which is obviously reminiscent of the opening of Apocalypse, is something that was constructed after the fact. But that came about as a result of something Francis had done early on with Corina. Originally, the scene of Dominic waking up at night and thinking about his life and walking to the café had occurred somewhere around scene 25. But Francis had decided to put that scene up earlier, and then I thought, “OK, if you’re going to do that, let’s see what he was experiencing before he woke up. Maybe we can get some of the themes into the film and lay down some of those images early on.” So that’s something that came up in post-production.

“When I assemble a scene for the first time, I do it with the sound turned off because I don’t want to be distracted by the soundtrack as it exists at that moment. I want to imagine in my mind the soundtrack the way it might be when it’s done.” – Walter Murch

CM: What other editorial suggestions did you make?

WM: One of the bigger shifts was to take the story of Dominic’s involvement with the Nazi woman and make it happen during the Second World War rather than after, so that these events take place in neutral Switzerland, which was obviously infiltrated with military people and spies from both sides of the conflict. So that the character, played by Matt Damon, supposedly working for Life and actually working for the Special Services department, tries to get a hold of Dominic and bring him to Germany because Hitler is interested in immortality, which apparently Dominic has achieved. This idea of making that happen during the war is something that we decided during post.

One of the things we were able to do was optically emphasize the swastika on her garter as the dissolve takes place. That was done within Final Cut Pro just by using a holdout matte so that as the scene fades into a dark scene, what lingers is this flesh tone swastika, which you may or may not have been aware of during the scene but which you certainly are aware of as the scene comes to an end.

CM: Speaking of Final Cut Pro, how has working with that system evolved for you?

WM: Francis made a very congenial decision for me because I had been using Final Cut ever since Cold Mountain, but Francis started using Final Cut when he shot in Romania, so his and my system simply merged into one stream.

CM: And was this the first time you worked on a film that was primarily shot digitally?

WM: Yes, I believe it was shot using two Sony F900S digital cameras and a film camera, particularly off-speed for time compression. But ultimately what we delivered was an all-electronic negative, you might say, in order to make the digital intermediate.

“One of Pete [Horner’s] approaches to discovering this [film’s unique] voice, where much of the action takes place on a metaphysical level, involved the creation of subtle resonances of sounds picked up from or suggested by the visual environment of the scenes.” – Walter Murch

CM: And how did it work out for you?

WM: I had much more latitude in the ability to recompose within the frame with digital acquisition because you’re not dealing with a grain structure. So we found that we could move the image around and play with it cinematically in ways that would have been quite cumbersome [and limiting] in film. And Francis had also decided creatively to use a lock-off camera unless he deliberately wanted to move the camera for story reasons. Once he set the frame, the camera was simply frozen in place and the actors had to move within that frame; there was no operator adjusting for where the people were in frame. If something really went off––if the actor strayed too far off––then they would have to do another take.

Frequently, a take would be very good but have a little too much headroom, so I was able to readjust very easily for that. Or I would blow the image up slightly to make last minute compensations for this effect without altering what Francis was trying to achieve, which basically was the technique he had used on The Godfather, in which edges of the frame don’t shift around trying to keep the actor in the center of the frame. If you look at the edges of the frame, for the most part, they are rock solid and don’t shift unless Francis wants a dolly shot. And, as a result, when the camera does move, I think it has a greater impact.

CM: What were your contributions to the handling of Dominic’s double?

WM: That was something I responded to very much in the screenplay. And when I saw the assembly, it furthered my love of that device and I wanted to see if we could find places where we could extend it and to have the double, who is such an interesting character, as a way of getting at the issues involved and also as an ideal way of getting inside Dominic’s mind. He’s had this lightning-induced schizophrenia and the double has a certain kind of diabolical charm to him and is very much an ends-over-means person.

In the scene in which the double makes his first enigmatic appearance in the hospital, Dominic turns and sees himself in the mirror for the very first time. And what you see in the film is that the reflection in the mirror turns before Dominic turns, so there is an asynchronous event happening all within the frame. And that was something that I thought up and that we were able to achieve just by simple matting within the mirror and then slipping the sync of an event that was happening at the same time. It was originally intended to be the moment that Dominic sees himself in the mirror and talks to himself. But now, because the person in the mirror turns before Dominic turns, and then calls out to him and tells him what to do, this is the moment that the double first manifests.

CM: What was the challenge of editorially shifting gears with the love story in the second half?

WM: It is a big shift in the movie. One of the ideas we had for a while was that it would go to black at the end of the first half and fade up to where he meets Veronica for the first time. But it seemed better to keep the momentum going and to cut from the closing of the safe door––which really ends the first half of the movie––and then go right from that, post-lapping the voiceover there into the scene where he meets Veronica.

Into his life comes the woman who will potentially give it meaning. We don’t quite know how, but he’s confronted with someone who is the reincarnation of the girl he loved as a young man and lost. Physically, the role is played by the same actress. And, on another level, they’ve been brought together by this same force of destiny: the lightning.

So we do shift gears, but by bringing them into close contact at this transition point rather than emphasizing the division, we allowed one story to spill over a little bit into the other. Other than the normal things that an editor does, I can’t think of anything we did extra to create the right mood appropriate to each scene. There wasn’t a big reworking, editorially.

CM: What’s your favorite moment of the film?

WM: It’s always hard to pull things out because an editor has such a strange relationship to a film compared to a normal audience. But I love the last scene in the café. There’s kind of a blessing to it in that it’s very unexpected and yet speaks on a deep level in some way of Dominic making sense of his whole life. The ghosts, these people from his past––who are presented as ordinary people––make themselves manifest to him. And as far as they are concerned, no time has passed at all—it’s still 1938. But he has been on this incredible journey into the future, which still has some foreboding to it.

CM: Talk about your continued work in sound. What importance does it still play?

WM: I guess I’ve been doing it so long that it’s second nature. In fact, I would love more editors to follow me. Certainly, it’s becoming easier and easier from a technical standpoint to do that because of digitization. Almost by necessity you are now obliged as an editor to produce a first assembly that has a much more finished soundtrack than was even conceivable 30 years ago when I first started out. At most, you had two tracks available to you. But now, Final Cut gives you 99 tracks and 24 outputs, so you can do almost anything you can think of to enhance the story through sound and temp music, or whatever resources you want to use.

A peculiarity in my case is that when I assemble a scene for the first time, I do it with the sound turned off because I don’t want to be distracted by the soundtrack as it exists at that moment. I want to imagine in my mind the soundtrack the way it might be when it’s done. And I can do that more easily if I’m only listening to the sounds in my head. That’s where some of the ideas of this first sound comes from: out of the silence when I’m first assembling that scene.

“One of the bigger shifts was to take the story of Dominic’s involvement with the Nazi woman and make it happen during the Second World War rather than after… This idea of making that happen during the war is something that we decided during post.” – Walter Murch

CM: What were the contributions of sound designer Pete Horner?

WM: Pete Horner, with whom I had worked on Jarhead, Apocalypse Redux, and the remastering of The Conversation, took on the essential task of sound design for Youth Without Youth, and he and I were also the re-recording mixers for the film. In addition, Pete was deeply involved in the film’s music––he is a musician himself––and was responsible for working with composer Osvaldo Golijov to select the orchestra and the two recording halls we used in Romania. He also pre-mixed the music for the final, and did all of the dialogue and effects pre-mixes in a room constructed from scratch in the old villa Francis had rented as production headquarters in Bucharest.

Pete hired the Romanian sound effects editors, taught them how to use ProTools, and supervised their work. We shipped a Digidesign Icon mixing board from the US and Pete installed this in the pre-mix room – a massive undertaking in itself. So, a huge logistical, technical and, most importantly, aesthetic burden fell on Pete’s shoulders––and he carried it all off with his usual deft combination of diligence and humor.

CM: Can you give an example of his aesthetic contributions?

WM: One of Pete’s approaches to discovering this [film’s unique] voice, where much of the action takes place on a metaphysical level, involved the creation of subtle resonances of sounds picked up from or suggested by the visual environment of the scenes. These resonances undoubtedly have a psychological effect in and of themselves, but they are also equally powerful at the point where they are silenced––like the hum of an air conditioner that you have become accustomed to, and notice only when it switches off.

These sounds were used to suggest not only the presence and quality of Dominic’s interior states of being––particularly those scenes involving his double––but also their sudden termination, when Dominic would re-enter waking reality. Just as important, they served as a sonic bridge between the more realistic “ordinary” sound effects and the music.

But above all, it is a great privilege to work with Pete, whose multiple talents in sound design and re-recording provide a great interlocking fit with my own idiosyncratic approach to post-production, which combines picture editing and re-recording. I felt many times as if Pete and I were runners in a relay race, handing off the baton to each other and then back again.