The past year has brought a reckoning on diversity and inclusion, for America and for members of the Motion Picture Editors Guild.

The death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in May was followed by months of social unrest. We were then challenged as a nation to move toward equality and inclusion, and as an industry to address the underrepresentation of women and people of color in our ranks. MPEG’s Diversity Committee invited Guild members to have a “sit down” discussion and “join the fight by holding ourselves accountable and to promote inclusive environments and actively work towards long-term solutions.”

The Guild hired Elevate Inclusion Strategies, a Vancouver-based consulting firm, to advise on issues of JEDI (Justice, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.) Elevate’s Natasha Tony and her team coached Guild Board and staff members in a series of sessions devoted to the issues.

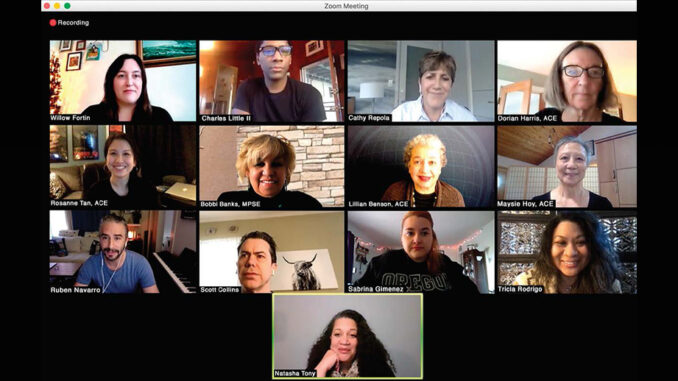

In December, Tony led a Zoom group discussion to further the discussion. Joining her on the call were Cathy Repola, the Guild’s National Executive Director, as well as members Bobbi Banks MPSE, Lillian Benson ACE, Sabrina Gimenez, Dorian Harris ACE, Maysie Hoy ACE, Charles Little, Ruben Navarro, Tricia Rodrigo, and Rosanne Tan ACE.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

Q Natasha Tony: Whose responsibility do you think it is to do more to advance diversity and inclusion?

Tricia Rodrigo: I think it’s everybody’s responsibility. We’re in a shared world. The world we create is with each other.

Charles Little: I feel that the responsibility lands on whomever has the ability to effect the change in the moment.

I served in the United States Navy, and we have a policy where we all take care of our certain sections of the ship so that the entire ship functions as a unit. If I’m walking through a passageway and I see something amiss, it is now my responsibility to fix it. Solely because I saw it. Solely because I can. It’s the responsibility of those who are in the position to actually effect the change.

Rosanne Tan: I feel that it’s very important for editors, producers, show-runners and the department heads to take a close look at their own crews. Because oftentimes, it’s very much about who you know. And if your crew is not diverse to begin with, and if you keep hiring the same people all the time, then change is never going to happen. In the past, the case has been that minorities and people of color haven’t had the privilege or been given the chance to move up. So I think people should want to make a change. And if and when they have the opportunity to recommend or hire someone of color or minority for a position, they should consider making a conscious effort.

When you’re the only person of color and a woman, there’s definitely bias.

Bobbi Banks: I was going to say almost the same thing regarding our industry. I feel that producers and execs should make an effort to look for people that qualify for various positions and also contribute to having a more inclusive crew. I also think that we should be mentoring others that are coming up, which is very important. Going out to high schools and underserved areas and to educating them on various areas that they otherwise might never have known existed. And so, I think the responsibility is actually on everyone. I would also say with that, though, I also strongly feel that there should be unconscious bias training at the studios and guilds — and thankfully, that has started for some.

Dorian Harris: The one thing that really is apparent to me, having been in this industry for so long, is that there hasn’t been that much change in what we’re talking about with diversity and inclusion. And, for me, personally, the responsibility that I feel about it is that now that I’m in the later phase of my career, it’s really important for me to give back to this business in some way.

Maysie Hoy: In terms of hiring, I mean, we seem to put it on the producers and the directors. But we as editors, we’re head of our department, you know? And I think a lot of it is up to us to create a diverse situation in our cutting rooms. The showrunners, they keep hiring the same people. I think it’s the comfort factor and reliability, it’s that you don’t go too far out of your bubble because, God, it’s such a high-pressure situation that you need people that you can count on. But I think that, more than anything, it’s just taking a chance on people. Giving them opportunities. I mean, that’s how I got into this business.

Sabrina Gimenez: It requires empathy, I think, on an individual basis. So, you know, as a white male editor, you can hire a Black assistant editor, but if you’re not going to understand why that Black assistant editor chooses to go to a Black Lives Matter protest in the middle of the day over something picture-editorial-wise, that to me is a disconnect in what it truly means to be an ally for your community.

Natasha Tony: If we just pull out diversity, it becomes tokenism, often, and it doesn’t ensure that we are in a culturally safe environment, which is the inclusion piece of it. So you hear me talk about JEDI. It’s short for Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion. What you’re diagnosing in your workplace analysis is that diversity alone doesn’t work and that we need the inclusion piece of it.

Q What is your vision for an equitable workplace?

Rosanne Tan: My vision for an equitable union workplace is a place where I feel that everyone can be positive, respectful, collaborative and inclusive always. A place where there’s no discrimination and people can embrace their differences together. A place where everyone can check their egos at the door and put their preconceptions on pause. Lastly, a place where everyone can enjoy long hours together!

Ruben Navarro: My vision for an equitable workplace is a place with respect and understanding when we can learn from each other. As storytellers, we can change the world telling stories, but we have to start making the changes in our workspace.

Sabrina Gimenez: Hiring individuals for both their job skills AND their positionality is the foundation to a strong equitable workplace. When we care about our colleagues and create environments where they can be productive and succeed, it’s crazy but that incidentally does improve the bottom line, as unbelievable as it might seem from the outset.

Maysie Hoy: My vision for an equitable workplace is one in which everyone has a voice. Everyone contributes. Everyone is respected.

Q Have you personally experienced bias in hiring practices? And if so, what was that experience like?

Lillian Benson: One experience that deeply affected me was an interview I had for a new magazine show at CBS in NY. I had just done “Eyes on the Prize” and been nominated for an Emmy. That series was seminal in my life and made me feel that “if I died the next day,” I had done something to make the world better. So this was my mindset going into this interview. I can still remember what I was wearing, because of course I always dressed very carefully when I went into an interview that mattered. The person with whom I interviewed was a white woman who was probably a little bit older than I, but not much. So I walked in, and her mouth dropped open. And I knew what that meant. That she did not expect to see a Black woman who had a resume like mine. And I thought it was ironic since the person who recommended me was an African-American male editor. So you know, automatically, I’m upset, hurt and then I kind of bristled. I didn’t get the job, which was okay because the job I did get after that was a PBS show that took me to California. After that experience, I decided to move to Los Angeles two years later. But I know in my heart that one of the reasons I did not get hired at CBS was race — the producer could not see me as one of her editors.

I’ve seen a lot of oppression at the hands of white men.

Tricia Rodrigo: I work on teams. Large teams of maybe 15 to 20 editors. And when you’re the only person of color and the only woman, there is definitely bias in the hiring practices. I cannot be the only woman of color who has skills and the ability to do this job.

Bobbi Banks: In an interview with a director who was white and whose cast was predominately people of color, he said, “Do you know how to shoot Black ADR?” My response was, “Well, what do you mean?” And he replied, “Well, you know, they don’t move their mouths much.”

Dorian Harris: Although I come from a position of white privilege, I’ve been subjected to a lot of oppression at the hands of white men in this business. For instance, I was hired to cut a very high-profile pilot for CBS a few years ago, and I was hired by the director, for whom I had previously worked. All white post-production crew, mostly male. The turnaround was so fast that we needed to bring on another editor, and they hired Farrel Levy ACE, who happens to be a friend of mine, but we had never worked together before. The pilot was picked up by CBS. We were never notified or thanked and we were never called to work on the series. And we knew that because Farrel had a friend who was a post producer on it. I wasn’t available, so I was never going to work on it. But Farrel did want to work on it. And the post producer said, “Your name’s not on the list. I have the list of all the people they’re going to be talking to, and I can’t believe it, but you’re not on it.” I had a friend who is an editor but was a producer on the pilot so I called him and I said, “Why isn’t Farrel on this list? We worked like dogs and you sold the pilot.” And he said — and this is coded language that they use for women frequently in scripted television — “We didn’t think that you or Farrel were good with action.” Everyone here knows exactly what that means. It just means you’re a woman.

Maysie Hoy: I first decided I wanted to go into acting. I went to a city college and I was studying to be a dietician. And so then I saw these kids in the commissary having a lot of fun, and I go, “What program are you in?” And they said, “Theater program.” I went directly to the guidance counselor there and I said, “I’d like to transfer into the theater program.” And she looked at me. She goes, “Are you sure this is what you want to do?” I go, “Yeah.” And she goes, “Well, you know there’s no work for somebody like you.” So I go, “Let me worry about that. Just please sign it.” I take it downstairs to the theater department with this Englishman from the Bristol Old Vic. And he looks at the paper and then he looks at me. And he goes, “You know, Miss Hoy, I think you should think about changing professions.”

Rosanne Tan: I’ve always felt that there aren’t a lot of women editors to begin with, and being an Asian American female editor is even more rare. I’ve experienced some bias even among my own peers, which is disheartening. About three years into my editing career, I met up with an editor I had assisted in the past. I was excited to tell this editor

I had landed a really big job. But their reaction and tone was sadly not what I had expected and their first words were, “How did you manage that?”

Ruben Navarro: I am originally from Spain and I’ve been living here for 10 years. So I didn’t grow up here, so to me, to listen to all of you is really powerful and such a learning experience to understand even better what people have gone through over the years in this industry. So, thank you for that. I haven’t experienced any problems that I am aware of during an interview. I got jobs, and sometimes I didn’t get them, and I never knew why. I don’t know if it’s something related to being from another place or having an accent or being queer. I haven’t got the feeling that that was a problem though. But again, I don’t know.

Cathy Repola: I’m really, really grateful to be here, for lots of reasons. I have a great deal of affinity for the membership. So hearing these stories is sort of breaking my heart on some level, because I hate that any of you experienced any of these things that you’re describing. But I’m so grateful to be hearing them because I don’t think we can change anything unless we have this kind of dialogue. So I’m happy to be here listening, participating. I really thank you all for doing this because, you’re putting yourselves out there, too, in a vulnerable place and doing it I think for the betterment…to help your fellow union members and the union to be better, and I really appreciate all that.

Natasha Tony: Thanks, Cathy.

In our industry, we need to incorporate the fact that reprisal happens, that retaliation happens, and you’ve identified very clearly, you know, the language around “artistic differences” — that you can have one-week severance, for some YOU just don’t get asked back. Have you seen some of that pushback, whether for yourself or for others, where there has been that retaliation for speaking up?

I don’t speak up unless I am willing to get fired.

Sabrina Gimenez: I am first generation American, my parents are from Argentina. Me working in the film industry is like their wet dream [laughs].

I’m considered “the millennial in the workplace who opens her mouth all the time” and is idealistic and is told, “You know what, you think and you say these things, and it just doesn’t work like that. Build a thicker skin.” I get told I’m hypersensitive, and as it turns out, I am hypersensitive, it doesn’t mean that I can’t do my job. But I have brought up instances throughout my career where I have felt discriminated against for being Latinx or queer.

I am very passionate about social justice issues, and sometimes it can be uncomfortable in the workplace. Do you want someone like that working with you when you’re trying to lock picture? “Do you want that person in your office who’s reminding you about real life stuff when you need to be hitting deadlines?”

Lillian Benson: I don’t speak up unless I’m willing to be fired. So when I speak up, I know I could be out of work tomorrow, and I’m ready for that. Sometimes I lose the job, sometimes I don’t. I accept — although I don’t like the fact — that sometimes people just don’t want someone like you there.

Rosanne Tan: This one incident happened much earlier in my editing career. There was a producer who, before me, worked with two male editors on the show. When I got assigned to this producer, I automatically noticed an attitude change. He was completely rude in the way he delivered his notes and ended up yelling a lot. When I was done with the job, I thought about it hard and finally decided to tell my boss. I really was hoping for a positive outcome since I’d worked there for a while. Unfortunately, he wrote an email to everyone in the workplace saying that he would work with the [producer] client directly. It was kind of a knife stabbed in my heart moment because I thought my boss was going to defend me. Instead, he didn’t say anything to the abusive client, and he told his coordinator to assign me easier jobs because I was “sensitive.” At the end of the day, speaking the truth backfired on me.

Tricia Rodrigo: I was working on a show that is a very specifically Asian-American-centered show. I was working on the pilot, and the company that had hired me had also hired me as the finishing editor for another show, so I had worked with them before.

So I now was brought on to this pilot that is Asian American, and I am Asian American. My parents are from the Philippines, I am the first generation, born here in America. The culture was of a different Asian culture, and though it is not my culture, I am very familiar with Asian and Asian American cultural politics and ethnic studies.

So when I see a scene and they’re walking into a backyard full of bonsai and I hear quintessential Asian music, it comes off as racist to me.

The company is run by two women, Caucasian women, and I saw them as allies. However, I do notice that all the content they’re creating is ethnic content. They had an editor on there before I even got on, and I told him that using that type of music occurs to me as fulfilling a stereotypical soundtrack that we have for people, and we’ve moved beyond that.

And so when I finally finished the job, I asked the executive producers, “So are you bringing on someone else from that culture to be an executive producer as well?” and they said, “No, we’re the executives.” Suffice it to say, I didn’t get a callback to work on the series at all.

Q What progress have you seen over the years?

Lillian Benson: When I started in the film business, I assisted an African-American editor. I learned over the years just how rare that was. My current job at Wolf Films (NBC Universal) is the most diverse editing environment I have been a part of. Of the 15 editors across five series, three are women, two of whom are women of color, and five other editors are men of color: two African American, two Latinx, and one Pan Pacific Asian. Change can happen.

Maysie Hoy: It is more diverse now. You didn’t used to see multiple people of color in the workplace. The world has changed and the old guard is changing with it. Plus the newer generation has a better understanding of what the world can be and they are more vocal about it.

Q CineMontage: What are your ideas about what we can do as individuals and union members to create positive change?

Bobbi Banks: We can begin to hire outside of our usual hires, be more sensitive to others and create a more open environment. Also, networks, studios and guilds could setup networking. mentoring and internship programs and partner with other organizations.

I wish I had a lot of money so I could make my own content.

Ruben Navarro: To me, the main tool we all have is communication. If we all share and listen, then we can empathize and learn from each other to make our workplaces better and, most important, safe for all of us to be who we are. I want to go to work knowing that I can be the Hispanic queer and happy person that I am.

Maysie Hoy: As individuals we can hone our awareness of other people’s feelings. We can become aware of what might not be going well for someone on a particular day. Our cutting room is a microcosm of our nation. We can’t be myopic in how we see the world. We have to be aware of the lens through which we are looking.

Sabrina Gimenez: I want our fellow union members to be more tolerant towards each other, approaching someone with empathy and kindness when conflict or misunderstandings arise, but also to not discredit anger when our colleagues face oppression or discrimination because it’s a very real and valid emotion. When we aim to understand the positionality all folks bring to the table, the industry becomes a better place to work for future generations of filmmakers, and the quality of our shows will reflect that.

Dorian Harris: When members come to me and complain about the Guild, it is usually due to lack of information and to disinterest in being involved. I always say, if you don’t like or understand what is happening in the Guild, go to a board meeting, run for a board seat, join a committee, call Cathy (sorry, Cathy) or a field rep or a board member or a staff member. Speculating about what you think the board is doing is useless. The Guild is very transparent. That’s what I’ve learned from working with the Membership Outreach Committee to get the Diversity Committee approved by the board. I’ve also learned that from being a co-chair on the Women’s Steering Committee and by running for and getting a seat on the board (after losing once!). Staff and members work very hard to try to transform the Guild to serve our ever-changing needs.

Natasha Tony: Often when we step up, then we are tone-policed that our energy is pathologized, you know, that we’ve done something wrong.

And I think that sometimes it’s not for us to fix; it’s just for us to name this and to be able to hold the folks accountable, that they need to do that work, right?

Tricia Rodrigo: I wish I had a lot of money, so I could make my own content. If I had the wherewithal to be making content for Asian Americans, or just people… using the level of sensitivity and understanding that I do have, then I would make it.

Natasha Tony: Yeah, so who gets to tell the stories is another question that comes up very much around access to the funds, who gets to tell the stories? And when we talk about accessibility, those initiatives can be something that we start to build in and promote and mentor others to do.

I am very passionate about social justice issues, and sometimes that can be uncomfortable in the workplace.

Cathy Repola: I’ve made a commitment, and I think the board of directors has, too, to keep this going, which is why we signed a contract with Natasha and didn’t just have her do a couple classes and then go about her life and let’s go about our lives. This is a long-term commitment for us, and I’ve said to all of you, this is important to me, and I think it’s important to the union. The time is way overdue for this, but the time is ripe for this. And we will have to keep doing this if we’re going to make a change. The board financially supports contracting with somebody like Natasha to do this and taking training themselves. Considering it’s only been a few months that we’ve engaged in all this, we’ve actually done quite a lot, and I don’t want to lose sight of that. I know people want change really, really fast, but we are doing things, and not everybody always hears about everything that we do. We have a big commitment to this, and we have a long ways to go. I’ve talked to Natasha about some of our white male members who were feeling like this is threatening. How do we make them allies and make them part of the solution and not be pushing against it so that this is a long-term change? The racism that’s systemic in this country is systemic in this industry, too. So it’s going to take a while for us to make a change, but I really believe in my heart and in my mind that we can do this. I think we can, and I think we have to.