by Ray Zone

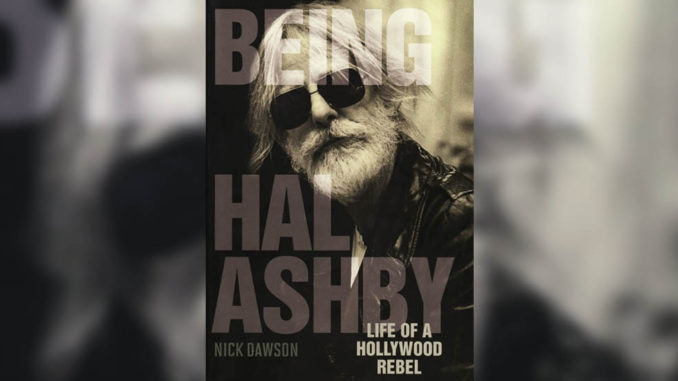

Being Hal Ashby

Life of a Hollywood Rebel

by Nick Dawson

University Press of Kentucky

402 pps., hardbound, $37.50

ISBN: 978-0-8131-2538-1

Hal Ashby is the pre-eminent “hippie director” of the 1970s. Like David Lean and Robert Wise before him, he started out as an editor and worked his way up to directing. He got into editing as the fastest route to becoming a director. When he worked at Universal in 1950 as a Multilith mimeograph operator––a job he secured through the State Employment Department in Van Nuys––directors there advised him, “Get into editing. With editing, everything is up there on film for you to see over and over again. You can study it and ask why you like it, and why you don’t.”

Nick Dawson has written the first biography of Ashby, a work that examines the director’s tormented personal life and childhood, and traces the troubled personal skein into an exemplary body of work in motion pictures––first as an obsessive editor who won an Academy Award for cutting In the Heat of the Night (1967) and then as one of the most “laid back” directors of the 1970s, whose most accomplished films include Harold and Maude (1971), The Last Detail (1973), Shampoo (1975), Bound for Glory (1976), Coming Home (1979) and Being There (1979). Dawson was originally inspired by Peter Biskind’s account of Ashby in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-And-Rock-‘n’-Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (Simon & Schuster, 1998), and has produced an amplified look at a man and an era of filmmaking that students of 1970s Hollywood films will find richly engaging.

Dawson has nicely balanced the personal and professional sides of a filmmaker who was nothing if not obsessive about his work. Ashby’s friend, cinematographer Haskell Wexler, remarked, “In life, Hal was the consummate editor, and some people ended up on the cutting room floor.” Undoubtedly, the suicide of his father, James Thomas Ashby, at the age of 54 in 1942 (Hal discovered the body) had a great impact on Ashby’s emotional life and a subsequent inability to form long-lasting personal relationships.

To a great extent, the obsessive nature of the craft of editing was for Ashby a form of solace.

In 1955, at the age of 26, Ashby secured work as an assistant editor to chief editor Gene Fowler, Jr. on a Western, The Naked Hills (1956) at Republic, the largest Poverty Row studio at the time. This marked the beginning of Ashby’s obsession with editing and his full-on commitment to the craft, spending long stretches of time in the cutting room. “When film comes into a cutting room, it holds all the work and efforts of everyone involved up to that point,” Ashby observed. “The staging, writing, acting, photography, sets, lighting, and sound––it is all there to be studied again and again and again, until you really know why it’s good, or why it isn’t.”

Ashby subsequently was hired as fifth assistant editor on The Big Country (1958), directed by William Wyler, and worked under Bob Swink, chief editor on all of Wyler’s films since Detective Story (1951). Wyler shot a lot of coverage and his relationship with Swink was both loving and volatile. The director openly solicited ideas from his crews and editors and his highly communicative relationship with Swink was nothing if not passionate and collaborative. Ashby later admitted that there had been “a lot of yelling, hollering and swearing that went on down in those cutting rooms, but there was also about 18 tons of love floating around there, too!”

Ashby had great admiration for Swink, who took the young assistant editor with him when he moved on to The Diary of Anne Frank (1959). In an article titled “Breaking Out of the Cutting Room,” Ashby acknowledged Swink’s influence upon his work. “Once the film is in hand, forget about the script, throw away all of the so-called rules, and don’t try to second-guess the director,” Swink would say. “Just look at the film, and let it guide you. It will turn you on all by itself, and you’ll have more ideas on ways to cut it than you would ever dream possible.”

By 1964, Ashby had completed his “epic apprenticeship” under Swink as editor with Gore Vidal’s The Best Man (1964). To a great extent, the obsessive nature of the craft of editing was for Ashby a form of solace. Dawson notes, “Despite the hard work he did there, the editing room was for Ashby a haven, a retreat from reality that allowed him to contemplate the world and his place in it.”

Nick Dawson traces the troubled personal skein into an exemplary body of work in motion pictures.

Ashby’s association with director Norman Jewison, on films such as The Cincinnati Kid (1965), The Russians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming (1966), In the Heat of the Night (1967), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968) and Gaily, Gaily (1969), was highly beneficial and productive for both men. “Hal Ashby was, without doubt, the most committed editor I ever worked with,” stated Jewison. And it was through Jewison that Ashby received his first opportunity to direct with The Landlord (1970). The Cincinnati Kid, in particular, showing real snap and drive in the filmmaking and editing, was important for both men. Jewison acknowledged that it “really kind of saved me emotionally” and said that it was “the one that made me feel like I had finally become a filmmaker.” “I also got my head together at the same time,” observed Ashby. “I was feelin’ good, and from there on, things really happened.”

With In the Heat of the Night, Jewison acknowledged, “So much of this film, and the success of this film…came through in the editing process with Hal Ashby. What is great about the editing––and what Hal preserved in this film constantly––is those moments without any dialogue, which essentially are the best moments in a movie, regardless of what the scriptwriters tell you, because it’s the human moments, the emotional moments that we hang on to.”

Despite winning the Oscar for editing In the Heat of the Night, Ashby was ambivalent about receiving the award, just barely showing up in time to take the stage at Santa Monica Civic Auditorium to receive it. “The competition—particularly Dede Allen who edited Bonnie and Clyde—was too good,” said Ashby. “I felt my award was part of the sweep for In the Heat of the Night. I went so far as to try and apologize to Dede, a friend of mine and possibly the best editor in the business.”

Though he did participate in editing the films that he subsequently directed, Ashby knew by 1970 that he was ready to move on to directing. “Studio editing rooms are the most depressing places in the world,” he remarked. “I worked in those tiny rooms with those institutional green walls till I thought I’d go crazy.” The world of motion pictures is the richer for it.