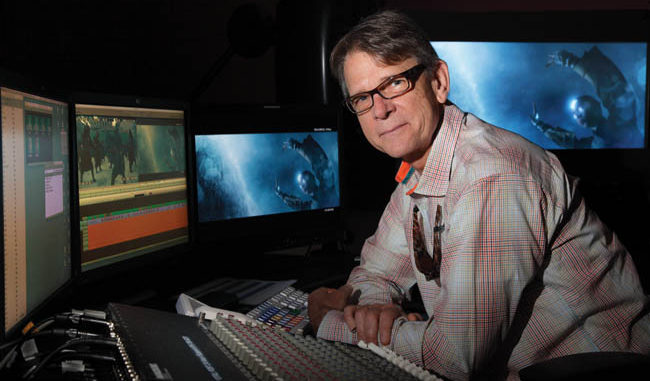

by Arman Tahmizyan • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

Known for having cut some of cinema’s most iconic actions sequences, largely in effects-heavy films, Oscar-winning editor Conrad Buff, A.C.E., is poised to add another CGI-laden title to his impressive list of credits when Paramount Pictures releases M. Night Shyamalan’s The Last Airbender July 2. A 3-D live-action film based on Nickelodeon’s animated television series Avatar: The Last Airbender, this is the editor’s second film in collaboration with Shyamalan.

Buff got his start in the business at an unlikely place: the US Navy. He cut documentaries in Washington, DC for the Navy’s Motion Picture Office during the Vietnam War. Following his service, he found his way into supervising visual effects, working on films like The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and Ghost Busters (1984). Soon after, he received his first picture editing credit on Richard Marquand’s Jagged Edge (1985).

With his background in visual effects and talent in picture editing, Buff went on to edit or co-edit some of Hollywood’s most massive productions, including Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), for which he garnered his first Academy Award nomination, and the worldwide blockbuster Titanic (1997), for which he shared the Oscar for Best Film Editing with James Cameron, A.C.E., and Richard A. Harris.

While overseeing the mix of The Last Airbender at Skywalker Sound in San Rafael, California, Buff found the time to speak to CineMontage about his current project, discussing some of the challenges on the film, his experience working with Shyamalan, and his philosophy of picture editing.

CineMontage: Did you cut The Last Airbender in 3-D?

Conrad Buff: No, not at all. It wasn’t originally destined for that format. Night [Shyamalan] did have some early thoughts about possibly shooting it that way, but I wasn’t party to that discussion. Very late in the process, Paramount decided that it would release the film in 3-D as well as 2-D. There are a lot of scenes in it that would lend themselves to that format, but it was not really shot or conceived that way.

While there is action in The Last Airbender, it’s not cut in an exceptionally quick pace, so I think a lot of it works more naturally in 3-D. By contrast, the recent Clash of the Titans was also a film that was converted to 3-D after the fact, and there were a lot of action sequences in it that were wonderful in 2-D––but which I don’t think worked particularly well in 3-D.

CM: What was the editing process like with M. Night Shyamalan?

CB: I had done his film The Happening [2008] before, so I knew what it would be like working with him. What was new for Night was having to lock visual effects sequences before shooting wrapped, because it takes so long to create and execute the CGI effects. There were certain sequences in the film that ILM [Industrial Light and Magic] knew would take six or seven months to accomplish. Normally, Night is not interested in anything to do with editing until he’s finished shooting, but here we had to commit to editing decisions and locking effects in order to make the dates. Overall, we were able to meet all of the targets required by the effects team. But we re-worked a lot of the characters and dialogue and really explored them fully.

CM: How does an editor gain the trust of the director––not only to continue working on his films, but to give him the peace of mind that he really is making the right decisions?

CB: If you haven’t worked with the director before, the initial trust is going to be based on your track record, your history, your resume––essentially, word-of-mouth from other directors. But in terms of the confidence or trust, the editor can only do it by demonstration.

For example, I like to feed directors scenes while they’re shooting in order to keep them abreast of how things are going. I think it helps them and it helps me. I’m also able to suggest if they might need additional coverage. Frequently, I’ll cut something that is structurally different than what they originally conceive, but honors the tone and color they were trying to achieve. It’s usually met with a positive response and can be changed or explored during the director’s cut.

CM: Having worked with sound designer and re-recording mixer Randy Thom on five other films, how different was the sound for The Last Airbender? Were there any new challenges or discoveries that the two of you made?

CB: There is a lot of sound design involved in this film, as well as a lot of original and complicated sound effects sequences that require some skillful minds and hands. It’s a complicated film with a lot of sound in it, but we were trying not to assault people with it, as so often happens with some action films that tend to be aggressive and can be assaulting in terms of sound. So we’re keeping it interesting and tasteful. And Randy, who is the sound designer and chief sound effects mixer himself, has come up with some very unique and interesting ideas, and it’s been a lot of fun.

“If you were to walk up to people on the street and ask them what an editor does, they’ll say, ‘Oh, those are the people who cut out the bad parts.’ For me, it’s quite the opposite. It’s not a subtractive process; it’s an additive process.” – Conrad Buff

CM: What is the mixing process like for you?

CB: It’s exciting to see it all come together because we have composer James Newton Howard’s real score, as opposed to the synth mock-ups that we’ve been living with for weeks. While his temp work is incredibly advanced in a synthesized way, live instruments in an orchestra really bring the film alive. Randy has the final ingredients to bring to the party, as Foley and dialogue are polished.

The mix is just a great period for me. I really enjoy this final finessing and polishing process. And it’s a great change for me because I’m no longer cutting; I’m making other decisions and seeing it come alive.

CM: Do you think the editor redirects the film in a way?

CB: Definitely. The director certainly has a vision for what he’s trying to achieve, but there is a certain serendipity to the process of making a film. Everything from composition, pacing and performance to art direction and lighting all impact your judgment and how you perceive things within the project. It’s an interesting process.

CM: Do you think one can recognize an editor by his work?

CB: It’d be very hard for me to figure out who cut a certain film without knowing the name of the director. I could assume that a certain editor may or may not have been involved, but the film material itself—more specifically, the dailies— absolutely influence the cut more than the editor. Films demand attention in various ways, so I don’t think I’d be able to pick out someone’s “style.”

CM: Having worked on so many of James Cameron’s films, is there a certain mentality with which you approach his films because of the fact that they are so epic?

CB: I don’t go in with a pre-conceived mindset, although I know I have to take a deep breath and be ready for the challenge. Jim’s films tend to be long-term investments, but he generates some of the best material. I have great respect for him as a director; he really does his homework and yet he provides an editor with enormous amounts of flexibility and room. My professional relationship with him has always been great. His material is always challenging––and he is challenging as a personality and a director because he really expects you to work as hard as he does. And he works harder than anyone, to tell you the truth.

Copyright 2010 Paramount Pictures Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

CM: You worked with director Antoine Fuqua; what was the most difficult scene to cut in his Training Day?

CB: Anything in the car between Denzel Washington and Ethan Hawke. While it appears to be visually simple, it was incredibly complicated because Denzel was experimenting wildly with the character. There were many, many opportunities for variation. In fact, two guys riding around on a towing rig car in Los Angeles for days on end results in a lot of changes in energy in terms of acting. They would get tired, they would be enthusiastic, they would be joking with each other between takes––and there would be serious tonal differences between the material within a given scene.

Bending, manipulating and unifying the performance and character was the most challenging thing in that movie. The material was there; it was about how you sculpted it. And I remember loving that movie for that reason––because it was a unique challenge. It’s one of my personal favorites.

CM: How was it working with Denzel Washington in the cutting room as an actor, and then as a director on the film Antwone Fisher?

CB: Pretty damn lovely [laughs]. Obviously, he loves acting and he hadn’t directed before, so it was an honor for me to be asked to do that. They were shooting on location while I was editing in Los Angeles, so I would send Denzel scenes just to reassure him and make sure everything was working.

Then, when he was finished shooting, Denzel was sweetly reluctant to come into the cutting room. Normally, directors are hot to jump in there the day they finish shooting. But I remember asking producer Todd Black when Denzel might be coming by [laughs]. I think he was a little apprehensive about what he created. But then he totally got into it; he was lovely. And that film also is another one of my personal favorites.

CM: What genre do you like to work in most and why?

CB: Hmmm… I’d have to say “variety” [laughs]. The one thing that I don’t tend to do is comedy. It’s something I think other people have a better knack for in terms of editing. But drama, thrillers, action, visual effects and those kinds of things––I have a very good understanding of those processes and know how to make those kinds of things work. In visual effects films, timing and pacing are tricky because not all the visual information is there. I’m able to structure the sequences fairly tightly with the absence of two thirds of the visuals.

CM: Do you feel that you take risks as an editor? And what does it mean to you, to take risks?

CB: Probably experimenting. Which is what we do anyway [laughs] maybe by turning a scene on its head, changing the meaning of the scene, and changing the direction and implications of the scene. Also, using the same material that was designed for one thing and reinventing it in a completely different way, to give it different meaning or tone. Sometimes that can be risky if you try something like that and present it to the director who wasn’t imagining that at all. But again, that’s part of the process, so I don’t think of it as being such a risky thing per se.

CM: Do you think of editing as a mechanical process?

CB: If you were to walk up to people on the street and ask them what an editor does, they’ll say, “Oh, those are the people who cut out the bad parts.” For me, it’s quite the opposite. It’s not a subtractive process; it’s an additive process. We’re basically cutting in the good parts. We’re saying that we like this, this and this––now how do we marry those elements and make it moving, scary, dramatic, emotional, affecting? It’s not a mechanical thing at all.

The longer I’ve been editing, the more impressed I’ve been with how one can manipulate the process and affect things in a way that they weren’t originally designed to be. That’s really what’s blown my mind more than anything over the years. I’ve developed more respect for the process the longer I’ve been doing it.

Arman Tahmizyan is a film school student and is in the process of joining the Editors Guild as an editor. He can be contacted at tahmizya@usc.edu.