by Peter Tonguette

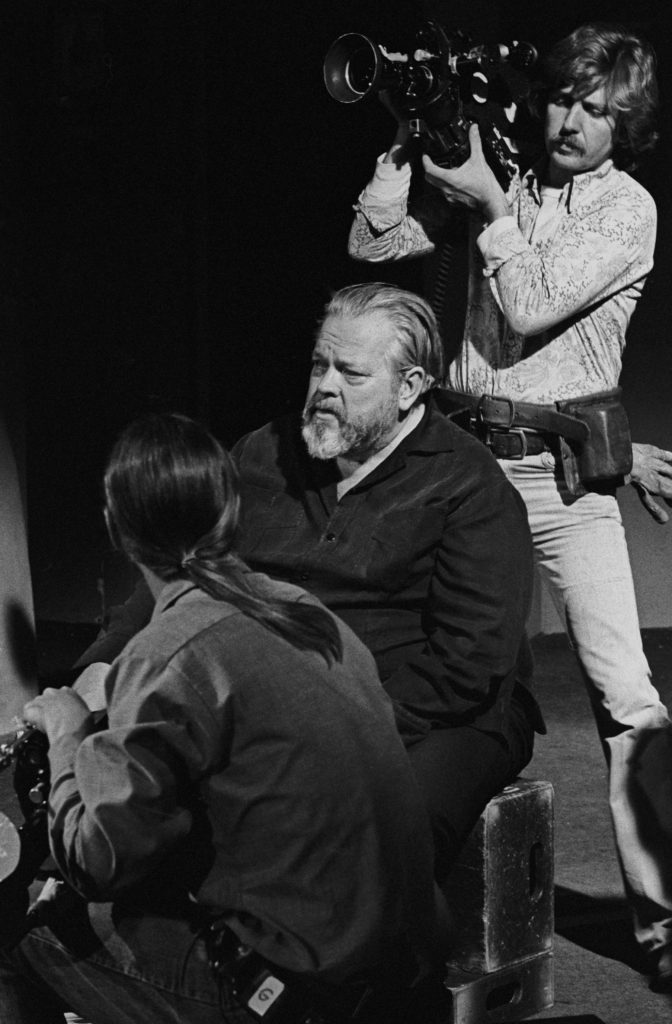

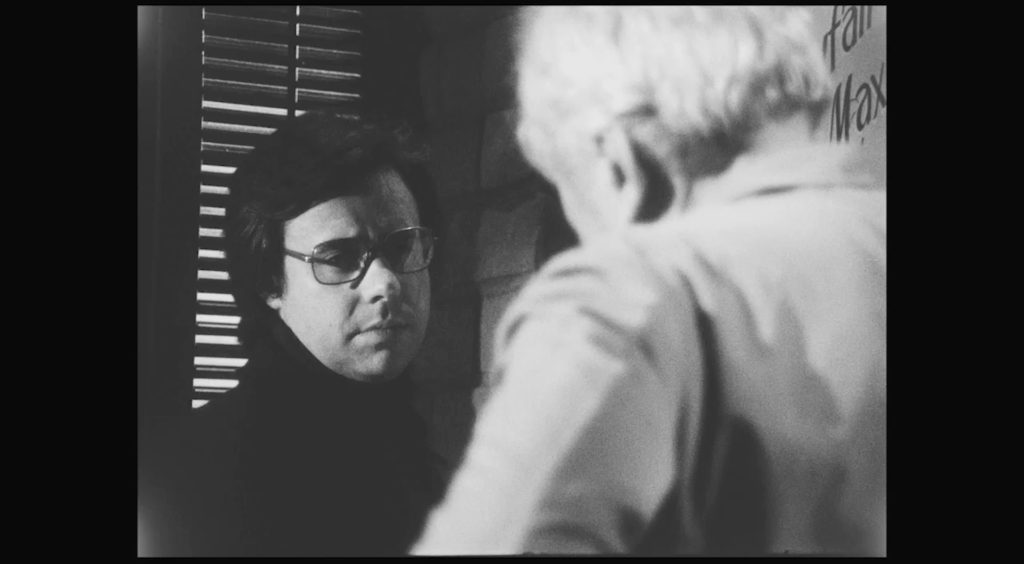

portraits by Christopher Fragapane • stills courtesy of Netflix/José María Castellví

Orson Welles was looking forward to editing The Other Side of the Wind.

In 1970, before he had even begun shooting what became his now-fabled unfinished (until this year) film, Welles discussed his post-production plans in a conversation with his friend, actor-director-writer Peter Bogdanovich, who was then interviewing Welles for their posthumously published interview book, This Is Orson Welles (1992). The screenplay, written by Welles in collaboration with his companion and muse Oja Kodar, revolved around Jake Hannaford (John Huston), a long-in-the-tooth filmmaker who has a personal friendship — and professional rivalry — with an upwardly mobile director, Brooks Otterlake (Bogdanovich).

The plot was provocative on its own, but equally scintillating was the style Welles was considering. “You hear conversations taped as interviews, and you see quite different scenes going on at the same time,” Welles explained to Bogdanovich. “People are writing a book about [Hannaford] — different books. Documentaries…still pictures, film, tapes.”

Welles said that “all this raw material” would be woven into The Other Side of the Wind — as would dailies from what is intended to be Hannaford’s current project: a sexy, surreal and sometimes incomprehensible film called (of course) The Other Side of the Wind. Footage was shot in multiple formats. “You can imagine how daring the cutting can be,” Welles told Bogdanovich, “and how much fun.”

Yet, for Welles, editing The Other Side of the Wind did not go as planned.

Financed through an unusual array of sources, including an Iranian production company, the film was shot in short bursts from 1970 to 1976, and post-production proceeded intermittently in Paris, Los Angeles and elsewhere. Due to a hornet’s nest of legal and practical problems, the film never made its way out of the cutting room; Welles was unable to wrap up post-production. When the iconic director of Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) died in 1985, the film was stranded in an unfinished, unreleased limbo.

Thirty-two years later, however, an editor was given the chance to experience the joys and challenges Welles anticipated in cutting Wind. Last fall, Bob Murawski, ACE, was hired to put the long-delayed film into working order. In this effort, he was joined by music editor Ellen Segal, MPSE, and a sound crew. On November 2, following its enthusiastic reception at September’s Venice Film Festival and elsewhere, The Other Side of the Wind will be released by Netflix in theatres and via streaming.

Yet Murawski — officially credited as co-editor with Welles — was not tasked with imitating the director’s style, at least not as audiences have come to know it. Indeed, for this film Welles had forsaken the carefully composed, deep-focus style that was his trademark. In a 1982 interview with the French film journal Cahiers du Cinéma, Welles agreed with journalist Bill Krohn, who said that the director’s style in Wind was “completely masked by two, as it were, borrowed styles” — that is, the documentary footage depicting Hannaford and the selections from Hannaford’s work-in-progress.

“It’s supposed to be the style of the character played by Huston,” Welles told Krohn, referring to the latter footage. “And it’s quite a good style. I’ve never had the guts to use it; it’s so outrageously self-indulgent. It was fun to make part of a movie that was not supposed to be mine.”

Consequently, Murawski did not feel the pressure of working in the manner of the master. “Orson always talked about how he was wearing masks,” Murawski told CineMontage. “He said that this movie was not even directed by him. He also said, on the one hand, that he’s wearing the mask of a documentary filmmaker. And then, when he’s making the art movie, he’s wearing the mask of Jake Hannaford — making a movie in the style of a director like Michelangelo Antonioni.”

In dealing with the material, Murawski had to set aside some of his own tastes, too. “I’m always trying to figure out how not to cut,” Murawski explains. “I like to follow the economical way George Tomasini would cut the Hitchcock movies, with real super-efficiency. But here was a movie where Welles seemed to want to edit as much as possible. As I was editing, I felt like I was wearing the mask of somebody other than myself as well.”

A Wellesian Destiny

Murawski is widely admired for working on such films as the Spider-Man trilogy (2002, 2004, 2007) and The Hurt Locker (2008), for which he shared an Oscar with his wife, Chris Innis, ACE. In some ways, though, he had been preparing to work on The Other Side of the Wind for decades. The Michigan native began his picture editing career with Danger Zone III: Steel Horse War (1990). As unlikely as it sounds, the low-budget biker movie had a Welles connection.

“The co-star of the movie was an actor named Robert Random,” Murawski remembers. “Whenever he was on screen, the movie was really elevated by his performance. I found out he had worked with Orson Welles — and, not only that, but everybody said he had starred in Orson Welles’ final movie.” That would be Wind, in which Random co-starred as actor John Dale — a strong, silent type whom Hannaford cast in his ongoing magnum opus. After tension develops between the two men, Dale exits Hannaford’s movie.

About 12 years after Danger Zone III, Murawski and Innis moved into a house in Studio City, when he would again cross professional paths with a veteran of Wind: indie-and-exploitation cinematographer Gary Graver. “I discovered that Gary was living three doors down from me,” recalls Murawski, who was an avid admirer of the DP’s work on Satan’s Sadists (1969) and The Toolbox Murders (1978), among others. “I saw him on his lawn early one morning when I was driving away,” Murawski comments. “A few days later, I introduced myself to him. We got to talking and became really good friends.”

Then Graver took Murawski on a tour of his garage. “I saw that he had a rack full of work prints that said ‘Orson Welles Productions,’” Murawski recalls. “I said, “Wow, so you worked with Orson Welles?’ He said, ‘I shot everything that he did for the last 15 years of his life.’” Graver shared with Murawski bits and pieces from Wind, prompting the editor — who, through his company Grindhouse Releasing, was in the process of editing another incomplete,’70s-era exploitation movie, Gone with the Pope (finally released in 2010) — to offer his services on Wind. “We had talked about maybe getting together to work on it when we were between jobs,” Murawski says. “Sadly, Gary had had cancer, and then the cancer came back. He passed away in 2006. I figured that was my last chance to ever work on that movie.”

Then, in 2014, The New York Times ran a story with a headline that surprised and delighted Welles fans: “Twisting Plot of Welles’s Last Film Nears an End.” Against all odds, Royal Road Entertainment, headed by producer Filip Jan Rymsza, announced that it would complete Wind, and Bogdanovich and Frank Marshall would sign on as producers. Affonso Gonçalves, ACE, was announced as editor, but as the post-production process faced delays, he moved onto other projects.

Last August, Murawski learned of the job opening from his longtime first assistant editor Dov Samuel, who had already joined the crew of Wind. “I really wanted to do the movie,” he recounts. “The funny thing is, when I interviewed with Frank and Filip, I thought that I wasn’t going to get the job. I just had myself psyched-out. I thought that they thought I was too mainstream.”

Not a chance. Murawski’s appreciation for, and knowledge of, exploitation cinema proved useful in trying to suss out Welles’ intentions for Wind. “I had this theory that Orson had probably seen some of Russ Meyer’s movies, because Gary had been dating Erica Gavin at the time,” the editor speculates, referring to the star of Meyer’s Vixen! (1968). “Russ’ saying was always: ‘Cut, cut, cut — create the punishing rhythm.’ Orson shot so much footage that it really enabled me to be able to do that. I really wanted to jam in as much as possible into the shortest amount of time.”

Scaling a ‘Dense Mountain of Footage’

Months before Murawski arrived, Samuel and second assistant editor Ray Boniker began the daunting process of sorting through the original footage — shot in both color and black-and-white, and encompassing an array of formats (including 16mm, 35mm and reversal film stock). For example, scene slates had been cut off.

“A lot of valuable information was lost, on top of the fact that all of the paperwork was pretty much gone,” Samuel says. “It was a very dense mountain of footage. We spent a long time deciphering what the scene was, based on some of the assembled scenes that Welles had done, asking, ‘What does this look like?’ It didn’t have any scene numbers.” Instead, Welles chose scene titles that related to shooting locations, like “studio” or “bus.”

Murawski began work on Wind in late October, but during the preceding month and a half, he immersed himself in all things Welles and Wind, consulting interviews with the director and familiarizing himself with many drafts of the screenplay. Meanwhile, a researcher was dispatched to the University of Michigan, which maintains archives of Welles-related papers. “I said, ‘Give me any versions of the script, any treatments, any memos,’” Murawski recounts. “They found a huge amount of relevant material and sent it to me.”

Missing in the plethora of paperwork, however, was any equivalent to the famous 58-page memo Welles penned to Universal Pictures executives after he was prevented from overseeing the completion of Touch of Evil (1958). That memo guided Walter Murch, ACE, CAS, MPSE, when he reconstituted Welles’s original version of that movie in the late 1990s. But no such document existed when it came to Wind.

“The problem was that Orson always thought he was just going to do everything himself,” Murawski explains. “There were a lot of memos going back and forth to editors in Paris, but those memos were primarily complaining about technical things, like the leaders not being done the way he wanted them. It’s not like he ever sat down and wrote: ‘This is the intention of this scene.’”

Early in the process, however, the post-production team was presented with the tantalizing possibility that Wind existed in a more finished state than had originally been thought. “In interviews in the late ’70s, Orson was saying, ‘Oh, the picture is 95 to 98 percent done; all we really need to do is cut the negative and do the sound work,’” Murawski says. What’s more, editor-turned-producer Steve Ecclesine, who worked on Wind in the mid-’70s, told CineMontage that Welles had prepared two work prints.

For his part, Murawski remembered seeing boxes in Graver’s garage containing what he assumed to be a work print. “It looked like a complete edited movie, but it turns out that it had been broken down into scenes over the years,” he says. As part of the search, the editor traveled to Tacoma, Washington (home of Graver’s son Sean), where a Betamax tape transfer of a work print — of sorts — was indeed located. But hopes for finding a complete version of Wind were dashed.

“There was about 40 minutes of material that was pretty fine-cut,” Murawski comments. “The rest of it was really rough assemblies — in the oldest, old-fashioned sense of the word. Literally, it would be four different takes of a line strung one after another. It was basically select rolls that Orson had built.”

“Orson would say that in the editing room he was the enemy of the film and he wanted to be as tough as possible.” — Bob Murawski

In the version prepared for release by Netflix, Wind runs 122 minutes. The editor breaks down the material this way: Approximately 52 percent of the film was edited from material Welles included in select rolls, but had not fully cut; another 28 percent consists of scenes that had been fine-cut by Welles; and 20 percent features newly cut scenes for which no reference existed. All in all, about 100 hours of footage was at Murawski’s disposal. “Unfortunately, our schedule was so short that, whenever there was an assembly or a select roll done by Orson, I tried to confine myself to that as much as possible. And, if I needed other pieces, then I went into the footage.”

For Murawski, the best place to start was the beginning. The screenplay calls for an opening narration read by Welles, but since the director never got around to recording the lines, an alternative solution was utilized. “There was a rough version of the prologue that Gary had put together, with just his own voice narrating it,” the editor says, but that wouldn’t do. Bogdanovich then suggested that he recite the slightly tweaked lines — not as himself but as an aged version of his character, Otterlake. “His character is looking back years later,” Murawski observes. “We recorded it for temp, but the way Peter delivered it was so emotional and heartfelt that we ended up using it in the final mix.”

A Russ Meyer Influence?

Then Murawski had to reckon with the first scene in the film: a bawdy film-within-the-film scene that takes place in a Turkish bath. He was not thrilled with the unedited material — “It was really grainy, rather poorly shot and didn’t have a visual point-of-view,” he comments — but since the screenplay explicitly called for its inclusion, the decision was made for the editor to take a stab at it. “I said, ‘Let me try a kooky, choppy, Russ Meyer-y version,’” he recalls. And that version — as jolting an opening to a Welles film as imaginable — is in the final cut.

Wind then segues to Hannaford’s story, in which the director mingles with assorted underlings and enemies, including right-hand woman Maggie Noonan (Mercedes McCambridge) and film critic Julie Rich (Susan Strasberg), on a studio soundstage. Hannaford and his crew then head to his desert mansion, where his 70th birthday is to be celebrated. “The arrival to the party was pretty much cut from scratch,” Murawski explains. However, several famous scenes that follow were not only edited by Welles but also widely seen in documentaries and television programs (including the American Film Institute’s 1975 tribute to the filmmaker).

One such scene depicts Hannaford’s assistant Billy Boyle (Norman Foster) showing rushes to studio executive Max David (Geoffrey Land, donning a hairstyle and attitude that evoke hotshot executive Robert Evans). In the version Welles put together for the AFI, the scene is interrupted by still frames and flashbulbs going off.

Yet Jonathon Braun, ACE, who worked on Wind in the early 1980s and was among the film’s original editors to meet with Murawski, remembers questioning the logic of including the stills and flashbulbs when cutting with Welles. “I said, ‘Orson, who’s point-of-view is this?’” Braun told CineMontage. “He said, ‘Point-of-view?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m confused who it might be that’s shooting the pictures. Is there a spy watching all this? Did some journalist sneak in?’”

Braun proposed trying a more streamlined version of the scene. “I don’t remember if we ever did or didn’t,” Braun recalls. “I remember him saying, ‘You know, you’re very Swiss, Jon. So precise. You always want an explanation for everything.’ I remember discussing this with Bob when we met while he was finishing the film, and I was thrilled to hear he had felt the same way when he saw it. Kind of validating for me — or maybe Bob is a bit Swiss, too!” Indeed, Murawski decided to strip out the stills and flashbulbs.

Some scenes were fully shot but had not been touched by Welles — not because he didn’t care for them but because he was confident in the material and was saving them for later. “I think he knew he had the dramatic scenes between Huston and Bogdanovich,” Murawski says. “He probably thought he could deal with those at any point because they were simple and he figured on the set that they worked okay.”

Other scenes simply lacked sufficient material to work as shot. For example, one scene shows budding filmmaker Jack Simon (Gregory Sierra) getting punched out at Hannaford’s party, but key shots showing the blocking featured celebrity impersonator Rich Little — cast as Otterlake in an earlier filmed version. In an inspired decision, Murawski used shots of Little, but presented him as a party guest, not Otterlake. “When I put it in, Peter’s reaction was, ‘Oh, we can’t use that — we got rid of all the Rich Little stuff,’” Murawski says. “I said, ‘Peter, he can just be another guest. So what if we have a little bit of Rich Little?’ There are all these other Hollywood party guests.”

By contrast, much of the film-within-the-film material — filled with knowing looks and bizarre interactions between Dale and a woman known only as the Actress (Kodar) — was edited, and re-edited, by Welles. “He was able to edit it without sound, which probably made things easier,” Murawski comments. “I think originally he intended that it was going to be a parody of these kind of European movies, but that the more he shot, the more he enjoyed shooting it. He probably felt free from having to deal with dialogue and story. It was just images.”

Amidst all of the footage — and all of the excitement of completing a film that so many have dreamt of seeing — Murawski concedes that it took him a bit to engage with the project. “I felt, ‘Well, maybe we’re going to put this thing together and only end up with an interesting curio,’” he says, but he eventually located the heart of the film: the alternately affectionate and acrimonious relationship between Hannaford and Otterlake — and the passive-aggressive relationship between Hannaford and Dale.

“For me, that was finding those scenes between Bogdanovich and Huston — those scenes where they’re alone discussing things, and Hannaford is drinking glass after glass of Chivas, completely plastered and talking about how he feels betrayed by John Dale,” Murawski observes. “Seeing those scenes, and putting them together, is when I felt like it had become a real movie.”

Settling Scores

Equally important in turning Wind into a real movie was the addition of music; the scenes Welles had left behind featured, at most, temp music.

Music editor Segal, who had worked with Murawski on several films, including the original Spider-Man, joined Wind in December. “I had experience with film, which helped a lot, because we started the process in film but ended up with digital,” says Segal, who met with Murawski, Rymsza and post-production supervisor Ruth Hasty. “Basically, they said, ‘Can you start next week?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’”

Like Murawski, Segal had to interpret Welles’ intentions from the scant clues he left behind. “Everything was in Orson’s head, basically,” she says. “The biggest challenge was that there was no director. You have Orson in the back of your mind at all times, and you want to try to stay as close to what you think he might have wanted, but it was a tough one. The film is really unique — it’s not a Citizen Kane-type story.”

Welles did, however, give a hint of what he wanted the audience to hear during the party set in Hannaford’s house. “There is a line in the film about a mariachi band, a jazz band and a gypsy violin — and they’re all supposed to be playing at the party,” Segal explains.

The music editor quickly realized that Welles’ wishes, if carried out exactly, would overwhelm the dialogue in those scenes. “The film is complicated enough without music — just trying to figure out where you are and what it is — that to add multiple layers of different styles of music would not have made it flow as well,” she says.

“You have Orson in the back of your mind at all times, and you want to try to stay as close to what you think he might have wanted.” – Ellen Segal

So, instead of a cacophony of music, Segal settled on a single style. “The style that played under dialogue the best was a jazz piano trio that could be in the background,” she relates. “We could bring it up, we could echo it, we could play it from different parts of the house, and the conversation would still go on.”

A score was commissioned by French composer Michel Legrand, who, decades earlier, Welles had hired to write the music for his film F for Fake (1973). “Welles had told Michel that he wanted him to score The Other Side of the Wind also,” Segal says. “Michel came in for the spotting session, and he immediately wanted to sit down and just watch the movie. His whole concept was that he wanted to write a requiem for the film.”

Legrand asked Segal to fly to France to work alongside him as they prepped for scoring. At the maestro’s chateau, she worked with him for four days. “Every morning, we would go over his material and we would work with his scores,” the music editor remembers. “Michel has never gone into the digital age because he doesn’t need to, but I needed to transfer his tempos and his measure metering into a digital format so that, when we recorded the orchestra into ProTools, we would have the correct bars, beats and tempos.”

This past March, when Legrand was hospitalized with pneumonia, she stepped in to produce the recording of the score in Paris and Malmedy, Belgium. “We had a responsibility to get this done,” Segal stresses. “For the last three days before scoring, I barely slept.”

The music editor describes Legrand’s score, especially the sections composed for the film-within-the-film, as a departure for the composer. “Michel has a very beautiful and passionate scoring sound,” she comments. “This was a very different style, and very cool. He was another facet of himself. It is very avant-garde: a lot of percussion and movement within the percussion and the orchestra.”

In the end, about 50 percent of Legrand’s music was used in the final film, as score and source — a decision related in part to producer Bogdanovich’s strong preference for using source music in his films. “Orson asked Peter to make sure the film got finished,” Segal explains. “Peter doesn’t really use score in any of his movies, so we had to decide how best to integrate Michel’s music for the film.” (The full score is set to be released on a CD co-produced by Segal and Legrand.)

For one scene with Hannaford and Otterlake — edited during Welles’ lifetime and seen on his AFI tribute — the director had put music to picture; he had selected an instrumental recording of Cole Porter’s “It’s De-Lovely.” “Welles had decided it was too slow,” Segal observes, “so he sped it up” — which rendered the recording difficult to listen to. “Michel actually came up with a great original piece that we used instead.”

Like Legrand, then, Murawski and Segal felt free to supplement Welles’ vision with their own. “Orson would say that in the editing room he was the enemy of the film and he wanted to be as tough as possible,” Murawski reflects. “Knowing how Orson felt about the editing process was very liberating. We didn’t have to take everything that he had cut as gospel. And I know it’s probably going to be controversial to people who have seen those scenes — ‘Well, how dare you re-cut the master!’

“But,” he adds, “I think Orson would’ve been the first guy to do it.”