by Patrick Gregston • portrait by Wm. Stetz

If asked about his career, Joseph A. Aredas will tell you it was not very interesting; “not exciting,” he shrugs. And when queried about the steps that built his resume, which led to his becoming head of the West Coast IATSE office, his eyebrows and palms rise as his shoulders slump, and he says, “I didn’t plan it.” As if that somehow makes it less remarkable…

But scratch a bit, dig a little deeper, and a far more textured and rich story emerges. Aredas’ first industry job was as a cinetechnician, designing and fabricating camera and editorial equipment as a member of IATSE Local 789 (which eventually merged into Local 695, the Sound Technicians, part of which was later ceded over to Local 683, the Laboratory Film/Video Technicians and Cinetechnicians) at the MGM machine shop in April 1967. Laid off after seven months, he was brought almost immediately into Consolidated Film Industries (CFI) to be the first person of color in the machine shop. Hollywood was freshly under court-ordered (but industry-resented) racial discrimination adjustment, and the city was still rebuilding after the Watts riots, with white flight to the suburbs, war protests and the Summer of Love all part of the circumstances — a somewhat less than ideal circumstance for Aredas to be the new guy.

Unlike the ubiquitous coffee-order-qualifying ritual of today, the new machinist — after a few simple assignments — was tasked with creating a complex, close-tolerance densitometer piece. He used calculations to establish the specification and parameters required before he committed to cutting any metal, and when he presented the part, his supervisor was dubious. “‘How do you know this is right?’ he asked me,” Aredas recalls with a tilt to his head and a bit of a smile in his eyes. “I told him I knew. He asked me again, and I said, ‘I just know.’” When the doubting supervisor tested the part, it performed flawlessly.

“He then asked me, ‘How did you do this?” Aredas continues. “And I responded, ‘You don’t know?’ When he shook his head, I said, ‘Well, you better keep me around.’” Aredas says he knew he had earned his peers’ respect when he saw them suppressing their smiles and laughter as he returned to his bench. “They knew what I had done; they were watching.” The new guy was OK.

Working at MGM previously was an eye- opening experience for him as well. “I discovered that movies, which I had loved to watch, weren’t made at all like I imagined,” he confesses. “They were making Ice Station Zebra, a John Sturges directed vehicle for stars Rock Hudson, Ernest Borgnine and Jim Brown.” Aredas takes a moment to re-create what he saw in his mind; “And when I saw the gimble that they had the stage on, and how they moved the set, I was like, ‘Oh that’s what they do,’” smiling at the memory of his education. In addition to being one of the people literally making the gears of the industry of magic, he also had assignments that included props and staging equipment.

UNION SERVICE CALLS

Later, while working at CFI, he was surprised to be tapped as shop steward for Local 789, replacing the former one, who became Assistant Business Agent. A few years later, that agent decided to retire. “I was wondering who the new person would be, and was asking around, when someone told me to ask the Assistant Business Agent, so I did,” Aredas remembers. “And he said, ‘Well, I was thinking it should be you,’ to which I said, ‘Oh, not me,’ but he reiterated, ‘Yes you.’” Aredas pauses and visibly reflects; his focus returns to the telling: “I guess sometimes people see things in us that we don’t — which is better than the other way around, when we think we have something we don’t.”

It could be that the agent had taken note when Aredas had encouraged a janitor — whom he thought had promise — to go to school and learn something more skilled “or at least the machine trade.” Aredas backed up his talk by attending classes with the janitor, eventually earning his own Machinist Associate’s degree — and obviously the respect of others.

On his view of service, Aredas credits his parents and his teachers. He was raised not far from Los Angeles City Hall, in what is now known as Historic Filipinotown. His father had emigrated from the Philippines; his mother from Portugal. “I don’t know how they got together, but they were good parents,” he says. School was important to them, and Aredas credits that education with much of his progress later in life: “My parents were encouraging. And the teachers were great. They all taught us that education was a gift — literally it was free — and we should build on it, make something of it.”

But he also mentions the profound effect of living through the Watts riots and wondering how he might make a difference in such a society. Rather than move out, he was moved. “I asked myself long and hard what I could do to make a difference, and it was difficult to come up with answers,” he reveals. One day, as a parent with a full-time job and studying for that degree in the evening, Aredas was talking in a group of students, when one — a young black man — excused himself from the group. Aredas watched him cross the street to aid a blind white woman. “I suddenly realized that actions are always what matters. I decided right then to start looking for the opportunities everywhere. That guy really showed me something — how to act like a caring human being.”

Aredas’ position as Assistant Business Agent of IATSE Local 695 gave him a strong background in organizations and organizing, as well as a unique perspective on the changes technology was making to the industry. Among his assignments was inspecting the many small operations that were starting to offer services. “I remember getting this address out in the valley, and going to a home where a woman opened the door. I said, ‘I understand your husband is going to do such and such a service here,’ asking as much as stating. And she said, ‘Yes, let me show you,’ and took me out to the garage where there was this one tape machine. I really didn’t see how they were going to do any bargaining unit work there, so I recommended not to sign them up as signatory to the contract.”

It was, he says, a precursor to the digital age. “Now there are little boutique operations all over, doing what used to be done in labs and facilities, without the benefit of a collective bargaining agreement,” he says.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE TABLE

This work also set up his move to the management side when he returned to CFI to become the Vice President of Labor Relations and Human Resources in 1987. “When I was asked to take the assignment, I had concerns about that situation and, in my voicing them, management committed to doing things by the rules, doing things right,” Aredas explains. “They stood by that, and we had a good decade there of solid support, being fair to the workers while the company did well.”

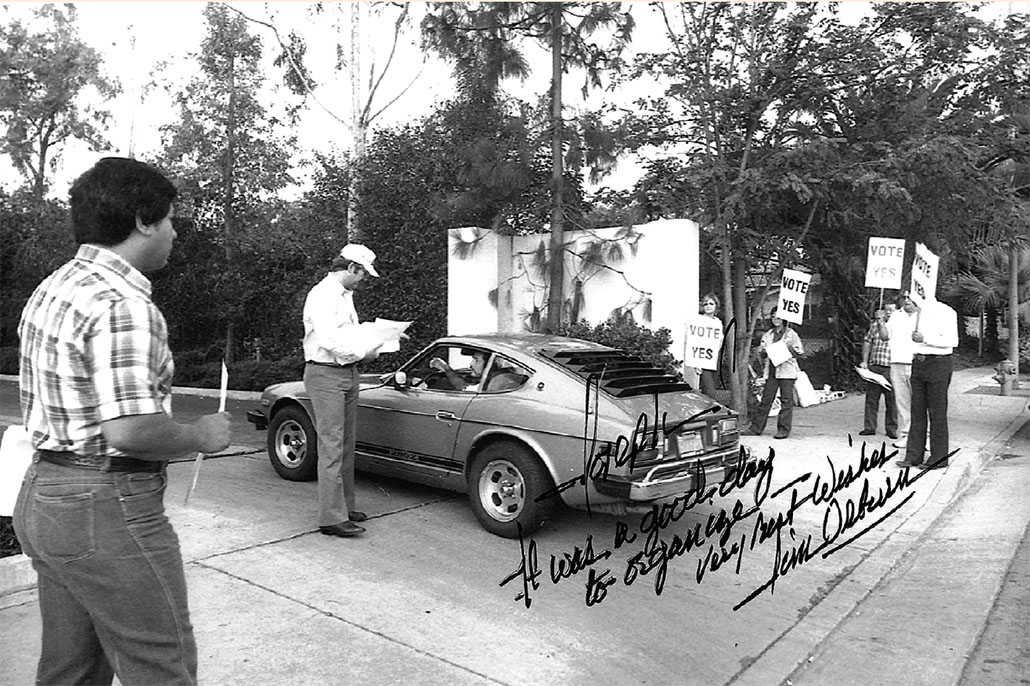

But in another example of an event that has become more common, CFI management changed, and the new CEO had some new ideas. “We all got trained by consultants to have missions, agendas and objectives,” he continues. “We would spend time working on these things, including writing up our own tasks. So I made one of my tasks ‘how to get rid of the union’ — as that was clearly what this new CEO was looking to do. I got and read the textbooks on union-busting, basically to create an impasse, force a vote, and then convince 50 percent plus one of the workers to vote the union out. And when I made that presentation, I made a point of exactly how that wouldn’t happen — the workers would have to give up their pensions and benefits, their terms and conditions and so on. And this guy says, ‘We can do that.’”

Aredas pauses , still wondering how someone could be so out of touch with the values and priorities of the people working for him. His eyes make a subtle dismissive expression, adding, “I made a point to renew as many collective bargaining agreements as possible before I left, because conditions there were not going to get better.”

Just before the dawn of the new century, Aredas returned to the service of organized labor as CEO of the Industry’s Contract Services Administration Trust Fund, and then as the International Representative in Charge of the IATSE West Coast Office, from which he retired in 2006, and then held many board positions with industry-related organizations, including the California Labor Federation, the AFL-CIO Entertainment Industry Development Corporation (EIDC), the Motion Picture and Television Fund, the Entertainment Industry Foundation and the California Film Commission.

It has not all been as easy or simple as that first challenge in the machine shop. “When you take an assignment, you have an idea of what you think the job entails, and how you will go about it,” Aredas considers. “But it doesn’t always work out that way. You have to adjust and find a way.”

So how did he find that way? Aredas opens his hand in front of him, palm up, and points to his thumb as he numerates, “Keep a smile on your face, especially when it is difficult; give your employer a good eight hours or whatever is required that day; do a competent job and do what you can to improve; interact with people because they are the best resource — always be fair; lots of people won’t be, but that’s their problem.” And as he arrives at his little finger, he pauses, makes eye contact and adds, “And you live up to your word — even when it costs you something or is difficult, because that is the honorable thing to do.”

Simple clear values, learned early and validated often throughout his career, have served Aredas — and those he has served — well. “I have always been able to put my family first,” he states. “The union, in its benefits and representation, has meant that I haven’t had to choose work over family.”

With a career that spans sprockets to digital, Cinerama to YouTube, Aredas allowed that pretty much everything has changed. “Even the unions; we’ve adapted too,” he says. In fact, during the years Aredas has been a union member, the West Coast IA locals have grown to now over 30,000 members — much of that during his tenure as head of the West Coast office.

When asked to assess the accomplishments of that tenure, Aredas has no hesitation. “The IA has been very good at reaching agreements,” he replies. “That’s because of the leadership. Maybe someday there will be an IA strike, but a huge part of our success is to keep our people working. We have kept our hands on the job, not allowing management or opposing unions to replace us.”

CONFRONTING UNION CHALLENGES

And this is key to what Aredas sees as the biggest challenge facing unions today: “Keeping the work here, being competitive on a level playing field, insuring the producers are motivated to do the work locally. With business concepts like Uber being the trend — where the individual takes on all the costs, liabilities and risks — we have to be vigilant and progressive. There has to be a successful business and industry for there to be a successful union. It’s a partnership between two opposing forces.” Just as important in his view is how to keep today’s generation connected to the basic issues and struggles that were part of how the union benefits and conditions came to be. “The industry is competitive, and people naturally are thinking about advancing their own careers,” he acknowledges, but then laments, “The kinds of lessons learned in establishing unions — working collectively to stand up to those who exploit fear, or even just standing up for other workers in other fields — are all in the past.”

Aredas points to the example of the late Miguel Contreras, with whom he forged IATSE’s relationship to the California Labor Federation, of which Contreras was Executive Secretary, as an example. “Miguel was a special person, in part because he had the childhood experience of experiencing his father being fired after 24 years of working for the same farmer — because he was a follower of Caesar Chavez,” he says. “Just as important, Miguel found a purpose and expression for that experience through his union work. It is a very interesting challenge to develop leaders today who have the ambition and creativity to be in our industry, yet have the heart and soul, along with pragmatic temperament, to do the work that unions do.”

The proliferation of small boutiques and facilities is not just an organizing problem. “We have to keep connected to our people,” he stresses. “We have to find the way to educate our members to participate, be informed and vote.” This is much more difficult as the workplace has become geographically spread out, and businesses specialize in parts of the process.

Lisa Aredas, Joe Aredas, Esther Aredas, Julie Stoddard, Kayla Aredas, Rosario Aredas; front row, Eva Aredas, Wyett Stoddard and Ariana Aredas.

Another aspect of today’s challenge is the effort to restrict union activities, part of which is “putting up money for different causes,” Aredas says. “It’s hard to give money out, because you are on a budget. And you can’t give money out of the general fund, because that is all predicated by the law. So it has been important to back politicians who are sympathetic — or will at least listen — to what you have to say. That’s all part of the challenge.”

The actual office Aredas occupied during his time as head of the IA West Coast office remains as it was when he retired nearly a decade ago. The fact that he is welcome to use it as he sees fit is as much a testimony to his accomplishments as the many honors that line the walls. Among them is one that certifies his lifetime membership in Local 683, which became a part of Local 700, the Motion Picture Editors Guild, in 2010 — with Aredas among those chosen as an MPEG Board member. Besides noting his “commitment, leadership, dedication and counsel,” the certification concludes, “But most importantly, for your compassionate sympathetic and humane demeanor.”

Spending time with Aredas reveals that as uninteresting as he might describe his career, the issues that have occupied his time and his guiding values turn out to be deep, compassionate and profoundly human. Security, fairness and respect for others (including the employers) have all animated his daily work, whatever the job title he held at the time. The nuts and bolts of union work — from the machine shop floor to working with public policy leaders in collaboration with other organizations — all originate from fundamental concepts executed with grace and humanity. The growing complexity and speed of change hasn’t altered these basic issues or values, just how we adapt to advance them.

When asked, “What is something we don’t know about Joe Aredas from his resume?” he looks inward again. And then, almost amused at himself, shares, “The one thing I have always been is a sponge. What I mean is that I look to see what others are doing and how they do it, and ask myself if it’s better than the way I do it, or if there’s a better way to do it. We have to be a sponge in this world to really succeed; and that’s what I’ve done, been a sponge.”

His previous comment is as self-effacing and minimizing as those other statements he makes about himself. Therefore, it is left up to us to take notice and recognize the truly remarkable fact that in his knowledge, observation, absorption, analyses and action throughout his long and productive career, Aredas has also been an extraordinary example of the values recognized in the Editors Guild’s prestigious Fellowship and Service Award that he is receiving.

If he was correct, that it really is “no big deal,” then MPEG would not be honoring him this May 2, 2015.