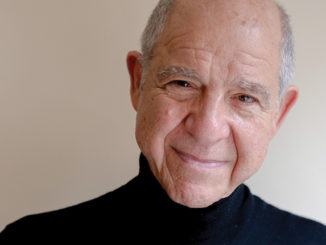

by Michael Ornstein, ACE

For me, growing up in the ‘burbs of New Jersey, going to the movies fed the imagination––which had turned a nearby vacant, wooded lot into my adventureland. My parents’ basement was a scientist’s laboratory, and who knew what secret treasures I might find hidden in the rafters of our dusty attic? In a classic chicken-and-egg sense, was it the movies that inspired me to play cowboys or knights or soldiers, or was it my imagination which found yet another outlet in a darkened theatre?

Typically, the movies that attracted me as a child were full of adventure. They transported me to a different world that was complete and perfect. Character was less important than exciting action and panoramic vistas, and the moral choices were pretty easy for a nine-year-old to discern. Particularly memorable was a Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis vehicle called The Vikings. I studied trumpet as a child and later, when I decided to double on French horn, the first thing I taught myself was the theme from that movie!

However, the first time I saw Lawrence of Arabia, it resonated far more deeply than anything I had seen to that point. I was stunned and overwhelmed. When it was over, I left the theatre in a daze, not wanting to break its spell, not wanting to leave the world that David Lean had created for me. The scenery, the sounds and colors, that magnificent Maurice Jarre score, the romantic world this movie allowed me to enter, the transformation of man into myth… I didn’t understand much of it at the time, but it opened my eyes to seeing films in a whole new way.

Peter O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence was a young, maladjusted lieutenant in the British Army during World War I. He gets a job as an observer with Prince Feisal, leader of the Arab tribal army fighting the Turks and, as they say, “goes native.” Lawrence became an inspirational warlord whose neutral presence among the tribal leaders (Omar Sharif and Anthony Quinn) served to hold them together in an uneasy alliance. (Lawrence’s efforts to unify the various Arab factions are particularly prescient given current events in the Middle East.) While wrestling with his own demons and the harsh desert environment, the Englishman also faces prejudices, which pit not only the imperialists against indigenous people, but also the mercenary practices of the Arab guerillas against the discipline of the British army. In the end, Lawrence himself does not know which side he is on, nor to which party he belongs.

If this film were to be made today, it would probably be criticized for the liberties it takes with history. But at the time, it made a man who was well known worldwide––but little known in the US––famous.

Lean’s direction, supported by the Academy Award-winning editing of Anne V. Coates, is flawless. Keep in mind that in 1962 there were no digital effects; those vast armies charging through swirling clouds of dust were choreographed and filmed. Yet compared to today’s styles, there is not a lot of cutting in this film. Lean was a master of camera and blocking, and every move served to further the story. Bold (for the time), hard cuts create transitions that thrust us forward. Notable among these is the close-up of O’Toole blowing out a match, which cut to an extreme wide shot of the empty desert at dawn.

Similarly, the introduction of Sharif as Sherif Ali is arguably the greatest screen introduction of a character in film. In this three-minute, nearly silent sequence, a mysterious figure emerges from a distant mirage. The precise cutting between this speck and Lawrence watching it grow into the figure of Ali on horseback, creates terrific suspense and underscores the mystery that attracts Lawrence––and consequently the audience––to the desert. Also, if anyone wants to know where Alec Guinness’ model for Obi Wan Kenobi came from, look at his performance here as Prince Feisal!

If this film were to be made today, it would probably be criticized for the liberties it takes with history. But at the time, it made a man who was well known worldwide––but little known in the US––famous. I believe in the spirit of historical accuracy, but we are storytellers and in story, interpretive artistic license will often get closer to the truth than slavish adherence to the facts.

Though my taste in movies has certainly broadened and matured, the nine-year-old in me has not lost that desire to be transported to another place and time. Immerse yourself in Lawrence’s more than three and a half hours. And if you have the opportunity to share the experience on a big screen, that’s even better.

Michael Ornstein, ACE, a picture editor and a Governor of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences, strives to believe in the essential goodness of man.