by Peter Tonguette

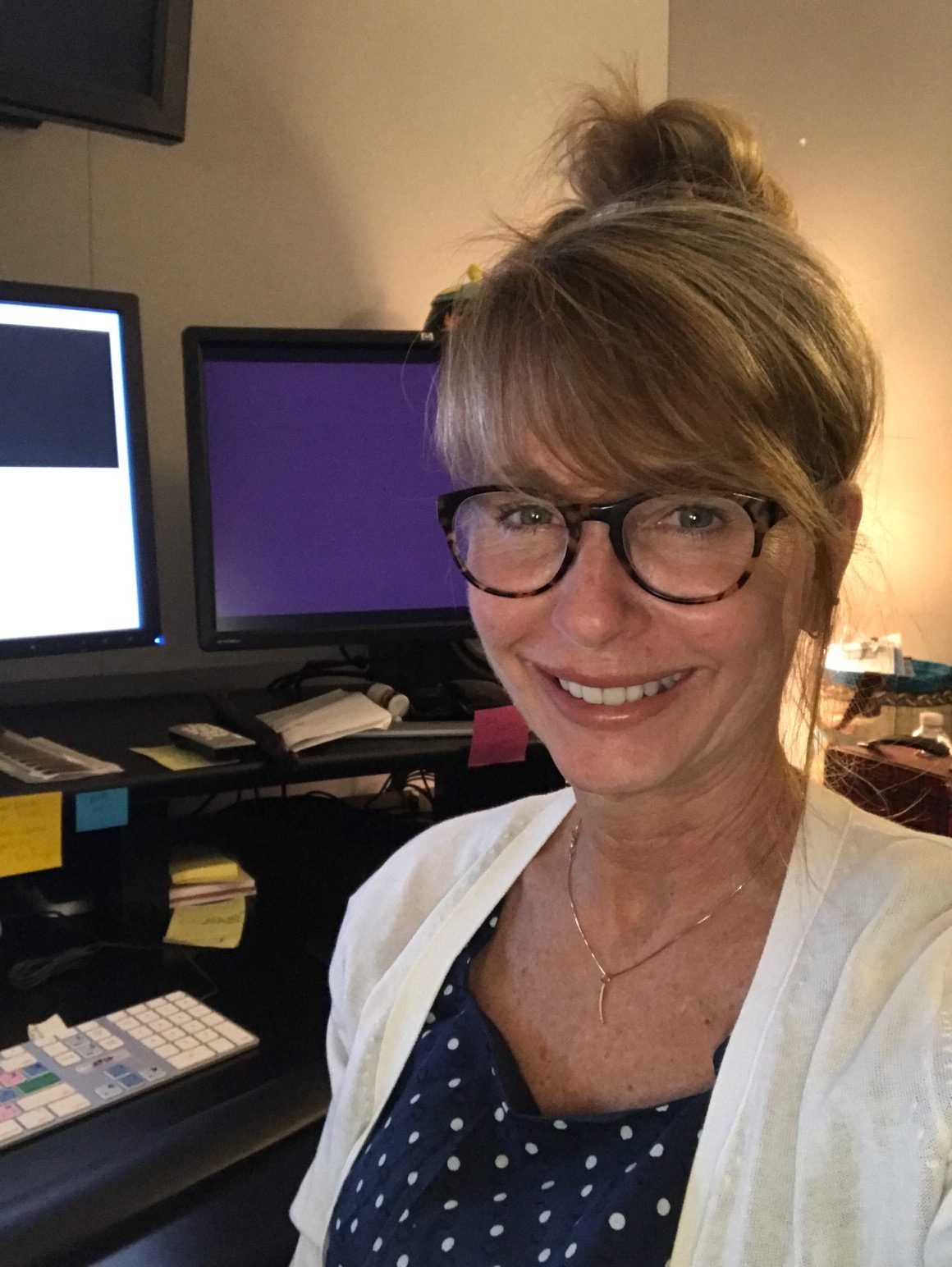

For four years in the mid-1990s, Julie Anne Lau counted among her collaborators a frog prone to singing and dancing, a conspiratorial-minded duck and a wascally wabbit.

From 1994 to 1998, as the editor of a series of hand-drawn cartoons made at Warner Bros.’ Chuck Jones Film Productions, Lau enjoyed a front-row seat to the exploits of such characters as Michigan J. Frog, Daffy Duck and — of course — Bugs Bunny. After a time, she got to know the ink-and-paint creations in much the same way that live-action editors become familiar with human performers.

“You look at them as actors — or whoever they are,” Lau says. “They are who they are.”

Lau worked with Chuck Jones (1912-2002) during his final stint at Warner Bros., the studio at which he established his reputation decades earlier as the director of innumerable short films featuring the cast of Looney Tunes, many of them classics. In the National Film Registry are a trio of Jones-directed efforts from the period: Duck Amuck (1953), One Froggy Evening (1955) and What’s Opera, Doc? (1957).

“I grew up with those cartoons as a kid and had an appreciation for Chuck Jones,” Lau reflects. “I savored looking at this beautiful artwork and all the talent that was there.”

A native of Sylmar, California, Lau was attuned to the art of animation from an early age: She planned to follow in the footsteps of her father, Sam Jaimes, who was employed as an animator at such studios as Walt Disney Productions, Hanna-Barbera Productions and Bill Melendez Productions.

“My dad was training me to be a clean-up artist or animation assistant,” says Lau, who began her career in 1978 as an inker and painter at Melendez. Soon, however, she shifted course. “Once I got there, I didn’t really like sitting and painting all day,” she explains. “I was young, it was my first job and they were training me.”

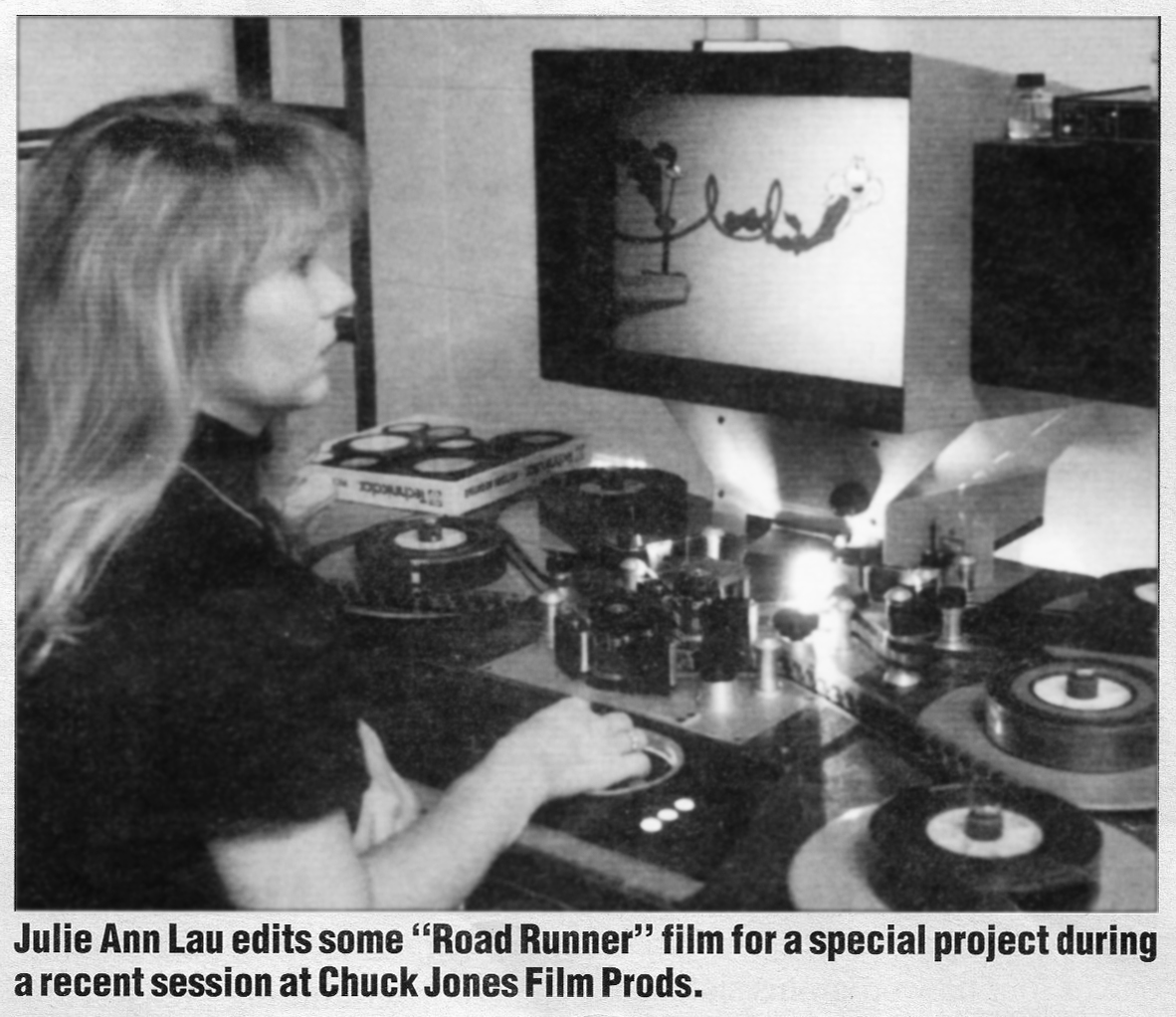

Setting aside her pen and paintbrush, Lau decided to move into the editing room. “I loved the sound of the Moviola,” she says. “I just liked film itself.” At the studio, she was introduced to every facet of animation postproduction.

“Working in a boutique studio like Bill Melendez, I learned a lot about aspects of the business,” she comments. “It was small enough where you were exposed to everything. I did the music, sound effects and picture at Bill Melendez, and then my career took me to cutting picture.”

After departing Melendez in 1988, Lau worked for a succession of studios, including Dream Quest Images, Horta Editorial & Sound and Hyperion Pictures, among others. In 1994, when she landed at Chuck Jones Film Productions, the noted namesake of which had only recently returned to Warner Bros. after having struck out on his own in the mid-1960s to helm such non-Looney Tunes projects as How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966) and The Cricket in Times Square (1973).

In 1995, The Los Angeles Times announced the news of Jones’s homecoming. “Nearly 32 years after the fabled Warner Bros. animation unit was shut down, leaving Chuck Jones hanging in midair,” wrote Dennis McLellan, “the veteran animator is once again turning out theatrical cartoons for the studio that gave birth to Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig and dozens of other familiar characters.”

“They needed an editor and somebody dropped my name,” Lau remembers. “I went and interviewed, and they liked me. My father was so ecstatic when he heard that I was going to work for Chuck because he was one of the few Dad didn’t get to work with.”

McLellan also reported that Jones planned to eventually produce 10 theatrically released cartoons each year, but in the end, only six were made in total: Chariots of Fur (1994), Another Froggy Evening (1995), Superior Duck (1996), Father of the Bird, Pullet Surprise and From Hare to Eternity (all 1997). Five were directed by Jones, and all were edited by Lau.

“We had a building just outside of the lot the first year, and then they moved us onto the lot into the original animation building that Chuck Jones was in during his younger days,” Lau recalls. “That was pretty cool.” Because production never picked up, the schedules for the greenlit cartoons were “luxurious,” she says. “We had plenty of time to do stuff, and I never felt crunched.” “Chuck loved telling stories, so I spent a lot of time listening to him tell stories. He was a neat guy.”

Among Lau’s favorite projects was Another Froggy Evening, which elaborates on the story told in One Froggy Evening. In the earlier cartoon, Michigan J. Frog transforms from a shy, sluggish amphibian to a swaggering crooner whose signature tune is “Hello! Ma Baby” — but only for the benefit of a single person at any given time. When the frog is presented to others, he is in his usual slothful state. In the sequel, the same joke is repeated over the course of several historical epochs, including the Stone Age and the Roman Empire. The cartoon concludes with a futuristic bit: After being taken aboard a flying saucer, Michigan encounters Marvin the Martian. “Oh, goody, goody,” Marvin says. “At long last, I have captured a perfect specimen of an operatic earthling: Frogeus Todei.”

“Who would have thought I would ever get a chance to work with Chuck Jones?” Lau says, reflecting on the short. “I was really excited to be a part of one of his projects that was reminiscent of a cartoon I watched as a kid.”

Lau also saw the cartoon as a chance to introduce a new generation of audiences to Michigan J. Frog, including those unfamiliar with the original One Froggy Evening. “They were bringing it back to entertain people who never saw the old one,” she says. “We didn’t have the boomerang that we have now.”

The pace may have been leisurely, but the process of editing hand-drawn animation was never less than painstaking. For Another Froggy Evening, after the completion of storyboards and the recording of some audio elements (including the frog’s songs and periodic ribbits), a pencil test was created to pinpoint pacing. “They shot that in-camera and I got it back,” Lau recounts. “I didn’t get them all at once. I got them in dribbles, and I cut and slugged spots for dialogue that didn’t have scenes.”

Lau had her choice of cutting on a flatbed KEM or Moviola, but she preferred working on the latter. “I never really liked working on the KEM because it wasn’t frame-accurate,” she comments. “When the KEM came out, the big deal was it had a bigger screen, so it was easier to look at, but I love the sound of the Moviola — that alone can give you timing.”

After the pencil test was edited, the material was turned over to a team of animators who worked on-site at the studio. “They didn’t send the shorts overseas,” Lau says. “They were still being done here. We had a lot of young guys out of Sheridan College in Canada.”

After a scene was painted and re-filmed, it was returned to Lau, who added it to a work print that consisted of both pencil and painted material. “You’ll get some color, cut it in and see how it works,” Lau explains. “You have a patchwork for a while, and then eventually you have all the color in.”

If timing was deemed unsatisfactory, Lau adjusted the number of frames shown of a particular drawing. “When the color comes back, if it’s not to their liking, I edit it,” Lau explains. “I can put it on ones or put it on twos, and make it snappier by taking out frames. In those days, we didn’t have the luxury of just cutting out a frame because we had to think about the negative and have handles for negative cutting.

“Sometimes you hacked stuff to get something, and then they sent it back to be re-animated to the timing that we wanted to create,” she adds. “If we lost a frame, we had to ask, ‘We need to have camera shoot us an extra hold here to make this edit.’”

Working as a team, Jones solicited Lau’s opinions when animated footage was screened during dailies or after a scene was cut. “He would always ask me for my opinion — how I felt about a scene or the timing of something,” she says. “He could always decline, but he would want to know.”

At the same time, Lau describes Jones as a perfectionist — not surprising since he had been overseeing the creation of cartoons for more than five decades by the time he was back at Warner. in the mid-’90s.

“He wanted what he wanted,” Lau says. “I remember the animators tried to make things great and fantastic, and they were doing an effect for an explosion on Superior Duck and going way beyond what was needed. Chuck said, ‘Give me a red flash and a yellow flash and a white flash.’ Sure enough, it came back and it looked great.”

So did Another Froggy Evening, which was released with the feature film Batman Forever (1995). Watching the cartoon again recently, Lau was left with an appreciation for Jones’ genius. “When Michigan J. Frog slides down the man’s hands like Jell-O, it was so beautifully done,” she says, referring to a favorite moment in the short.

Of course, the final judges of cartoons should be their intended audiences — in Lau’s case, that meant her daughter and son, the latter who was born during her tenure with Chuck Jones Films Productions).

“Everything you work on, you want to show the kids, and then they end up watching it because Mom worked on it,” she says. “You never have to ask a kid; all you have to do is listen to their chuckles or them saying, ‘Oh, look!’ You know when they enjoy it. My daughter, who was seven when I worked on Another Froggy Evening, laughed and enjoyed it as much as I enjoyed One Froggy Evening when I was her age. Maybe it will hold a special memory for her because her mom worked on it.”

In 1998, when Warner Bros. cancelled further short films from Jones, Lau departed the studio. “That was my segue into digital,” she says. “I went to Nickelodeon and got on the Avid.” But she remains fond of her time spent with Michigan J. Frog and other pugnacious imaginary animals.

“I really enjoyed that studio, the atmosphere and the people,” she says. “And who wouldn’t want to work with Chuck Jones?”

Editor’s Note: The “My Most Memorable Film” column, which appears regularly in the print edition of CineMontage, will now be featured periodically on CineMontage.org, giving Editors Guild members more opportunities to discuss noteworthy projects from their credits.