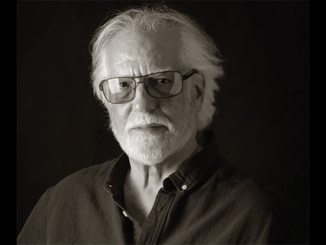

by Debra Kaufman • portraits by Damon Loble

Ten years ago, negative cutter Mo Henry, who owns D. Bassett & Associates negative cutting company, gathered her employees together for a talk. It was time for them to look for another job, she counseled, because the move to digital cameras and digital finishing would put an end to film — and certainly negative cutting. “I told them to find a place they could go with their skills,” she recalls. “But I was wrong. I thought this would end fast, and I’m shocked that I’m still doing it.”

In fact, D. Bassett & Associates is quite busy, with three union negative cutters and a PA on staff. The company just finished cutting a Christopher Nolan project and is expecting another “big film” soon. The company also spends a lot of time archiving film footage for Warner Bros. and Sony features shot on film but finished with a DI. Historically, the position of negative cutter dates back to the early days of cinema, when it was one of the first post-production jobs.

Of course, her company doesn’t have much competition; Henry believes she owns the last union negative cutting company, certainly in North America and, quite likely, the world. After a talk about her career at the Hollywood Post Alliance Tech Retreat in 2010, Henry ended up with a Wikipedia page and a Facebook fan club.

That’s quite the journey for the woman who very reluctantly joined the industry after graduating high school in 1974. Her father, himself a union negative cutter, heard that Universal Studios was so busy that the union had run out of members to call. “The union [IA Local 683, which merged into Local 700, the Motion Picture Editors Guild, in 2010] allowed them to start hiring off the street, and my dad heard about it and offered me the job,” she recalls. “It was an unusual way to get in.”

Although Henry was already living on her own with a dream of being an interior designer, her father insisted she take the job. Her shift was 7:00 p.m. to 4:00 a.m., and her colleagues were “salty old women,” as she describes them. “I was probably half the age of everyone else there,” she says. “Now I’m one of the old ladies I used to work with!” The first thing she learned to do was to break down film; in those days, the negative cutter wouldbreak down every shot in a TV show or feature. “I started in opticals, which were the fades, dissolves and effects created there on the same floor as the optical department,” Henry relates. “The reason they started me with these was that they could re-create them if I made a mistake.”She quickly discovered she had a knack for the work. “I had the right personality and I was accurate,” she says. The first feature Henry worked on was Jaws(1975). “At the time, the movie was in trouble and Verna Fields, an editor dubbed ‘the film doctor’ was involved,” Henry recounts. “My boss, who happened to be my dad, asked me to start on it. He said, ‘It looks like it’s headed straight for TV, so if you make a mistake, nobody will know.’”

When Henry couldn’t get off the nightshift at Universal, she left for Quinn Martin Productions, a TV production company. “I bounced around at different TV production companies and labs, including CFI and Lorimar, ” she says. “I liked TV because they’d go on hiatus during the summer, so I could work for nine months and then take the summer off at the beach.” Because there was such a divide between features and TV, Henry found herself focused on TV shows, including The Waltons, Eight Is Enough, Cagney & Lacey and M*A*S*H. “I loved cutting M*A*S*H,” she says. “It was only half an hour and the style was lots of long takes. Each reel had very few cuts, so it was fun to work on.”Although 90 percent of the cutting she did in the late ’70s was episodic TV, as an employee Henry did cut a reel or two of a feature for another cutter. “I had done some breakdown on features prior to learning to cut,” she says. “The first feature I recall working on was The Empire Strikes Back [1980] for a cutter named Bob Hart.”

In her mid-20s, Henry tired of cutting negative and quit to become a real estate agent in Beverly Hills. “I loved houses and designs and thought real estate would put me in all these great houses,” she says. “But it wasn’t what I thought it would be.” Soon she found herself back in the industry, as a PA for a commercial production company. She worked her way up to production coordinator but quit when she got pregnant and gave birth to her son Logan. When she and her husband were about to lose their insurance, it was time to go back to work. By then, her cousin was running Universal’s negative cutting department, and she was back where she started 10 years earlier.

She wasn’t at Universal long before she started getting phone calls from the legendary negative cutter Donah Bassett. “Donah had a reputation for being really mean,” says Henry. “She finally asked me why I kept saying no to her and I said, ‘Because you’re mean.’ She was taken aback and promised she’d be nice to me. I said I’d give her two chances and, number two, I’m walking out.” Bassett went out of her way to be overtly sweet to Henry. “Then one day, when she thought I was there for good, she said two or three nasty things to me in front of the crew,” Henry recalls. “Referring to The Wizard of Oz, I said to her, ‘Did you buy that house or did it fall on you?’ Then I said, ‘That’s one,’ and went into my cutting room.”

Working at D. Bassett & Associates was also a tremendous learning curve for Henry. “It was the first time I was thrown into such a high-pressure situation,” she says. “From then on, I cut features exclusively. I had never had to deal with things like multiple-language soundtracks, multiple elements like interpositives, internegatives and overlays. Avid and Lightworks were beginning to catch on, and those were challenging, but most of all, it was the deadlines, the pressure, the constant changes up until the 11th hour, recuts, massive visual effects, marketing requirements and, most of all, the politics.”

Three months after Henry went to work there, Bassett asked her to have lunch. “I said, ‘If you’re going to fire me, just do it; I don’t need the Last Supper,’” remembers Henry. “I really didn’t want to go, but we sat down at the bar at the Smoke House. Once we sat down and ordered drinks, she pushed a folder over to me and said, ‘I want you to buy my business.’ I was shocked, speechless.”

Henry went home that night, told her husband and the two had a laugh. But later that weekend, they opened the file that Bassett had given her, and realized that, for financial reasons alone, she had to do it. Henry found herself the owner of D. Bassett & Associates, but was lacking critical skills. “I was still on my learning curve with features, and I also had to navigate owning my own business, managing a large staff, dealing with the IA as a producer, and working directly with studio heads and filmmakers,” she recalls. “I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.”

In the 20 years since she’s owned the company, Henry and her team of negative cutters have worked on a laundry list of well-known features from Transcendence, Interstellar and The Dark Knight Rises to Shrek and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. She was the negative cutter for Woody Allen films up to and including Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008); the director began finishing digitally after that film. “I loved cutting for Woody Allen,” she says. “He has the longest takes in the world. A normal reel has 300 cuts, and Woody would have 35!”

Allen isn’t the only famous director with whom Henry has worked, and she has stories on many of them. “When Dona retired, she introduced me to all her clients,” she says. “It was an old boy’s club and many people gave me a hard time, but two people — Mark Solomon, the head of post at Warner Bros., and Jimmy Honoré, head of post at Sony — were really good to me.”

Bassett also introduced her to Joel Cox, ACE, Clint Eastwood’s editor. She remembers, “When I had the first film to cut for him, Joel said, ‘We’ll give you a chance, but no one else may touch the film but you,’” Henry says. “That was really difficult because I’d have to stop managing to cut a whole feature film. For the first four or five Eastwood films, that’s how it was. When Joel called for the next one, I said, ‘You’ve got to let me get some help.’ He said, ‘No,’ but when I started giving him names of other cutters, he finally let me get help.”

One of her favorite directors to work for was Oliver Stone. “It was like a circus,” she smiles. “He was hilarious and would come in for a screening right around the time I was supposed to go home. He’d find me in the cutting room and was very distracting. Once he tried to convince me to put the negative up and cut it right there, with him over my shoulder. He insisted and took out his checkbook. But I told him, ‘No, you can’t do this; it’s a terrible idea.’”

Among her all-time favorite films for which she cut negative is The Matrix(1999). “It was so exciting; we’d been told about all these new, experimental things that had been done,” she says. “It was insane hours, weekend after weekend with a full crew. I was later told it was the most expensive negative-cutting job ever — my bill was $100,000 when a normal film was $10,000 or $15,000. The editor, Zach Staenberg, was also my friend, and he won an Oscar for it.

Earlier in her career, Henry cut Ghost (1990) when she was an employee at Paramount Pictures. “Fortunately, I was cutting in sequence,” she says. “When you cut with a work print, you take a look at the shot so you can determine if you actually have the right shot; in the old days, key numbers were duplicated so you really had to stare at the shot in the positive print and then the negative to eye-match it.” Although there was no sound, cutting Ghost in sequence allowed her to follow the story. “When I got to the scene at the end when Patrick Swayze comes back as a ghost, I was crying my eyes out,” she says. “And I was right…it was a big hit.”

“I thought negative-cutting would end fast, and I’m shocked that I’m still doing it.” – Mo Henry

Another favorite is Garden State(2004), the indie movie written and directed by actor Zach Braff. “It was done on a shoestring and the editor was Myron Kerstein,” Henry recalls. “We’d hang out at Zach’s house in Laurel Canyon and wound up having this film school to get it done. I had always been in the lab before and never actually worked next to filmmakers. They were great people. I got treated like a real colleague and it was really a pleasure.”

Although the future of film didn’t look bright when Kodak appeared to be winding down its film-centric activities, directors like Nolan, Quentin Tarantino, J.J. Abrams and Judd Apatow banded together with studios to save the medium for use in filmmaking. “When people realized film was an option, gard,” Henry reports. “People who would have chosen to work with film in the past didn’t because they were afraid film would dry up mid-production. Once everyone knew the film would be there, people started shooting on it again.”

Bassett & Associates continues to be busy with archiving of film for features shot on film but finished in a DI. “My group gets the Avid list from editorial and we pull out all the shots that ended up in the final product and put them together reel by reel,” she explains. “We have a logging system that combines computer software and old-fashioned synchronizers to create metadata for the studio to use. It’ll tell you the event number, scene and take, original lab and camera rolls. It’s a GPS for scanning the film and re-assembling it.”

What does Henry think now about the future of film? “I think it will continue to be a boutique way of filmmaking by a handful of people,” she says. “But I don’t think it’ll ever really have a renaissance as far as the number of people doing it. There are fewer people in the Editors Guild who know how to handle film, and there aren’t the resources needed. When we were cutting The Dark Knight [2008], Chris Nolan’s editorial team called to ask for splicing tape, and we went on eBay and Facebook to find it. That’s where we are. It’ll be difficult to find the stuff and it’ll be expensive. Only big filmmakers will be able to shoot film.”

And will there be negative cutters? “I begged my people to buy my company from me, but they don’t want to,” responds Henry, who plans to semi-retire in August. “All of my talk about the end of film came back and bit me.” Still, she notes that she employs three union negative cutters who can take over: Andrea Ficele, Jim Hall and Phyllis Modugno. And she’s not going anywhere for a while. “I’m sticking around,” Henry says. “I want to see where all this ends.”