by Norman Hollyn

When I look at an editor’s credit list, I find that there are two reliable indicators of his or her success. The first is whether the editor has worked with directors or producers more than once. There is no greater testament to an editor’s value than to be trusted a second time with an artist’s “child.”

The second indicator of success is the variety of an editor’s projects. As editors, we are all chameleons; we aren’t paid to have our own styles, our job is to take on the style that the movie demands of us. A valuable, collaborative editor is as comfortable and successful at finding the story, pacing and character in a comedy as he or she is in a drama or a musical.

On both of these criteria, Paul Hirsch scores big. He has worked for directors like Brian DePalma, John Hughes and George Lucas many times. He has worked on films as diverse as the science fiction space operas Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back and the thriller Mission Impossible. He has done the horror films Carrie, Obsession and Creepshow, as well as the teen comedies Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Footloose. He has done the musicals The Fighting Temptations and Phantom Of The Paradise and the unclassifiable films Hi Mom!, Blow Out, The Black Stallion Returns and Hard Rain.

In short, he is a man in demand by many, for a huge variety of films.

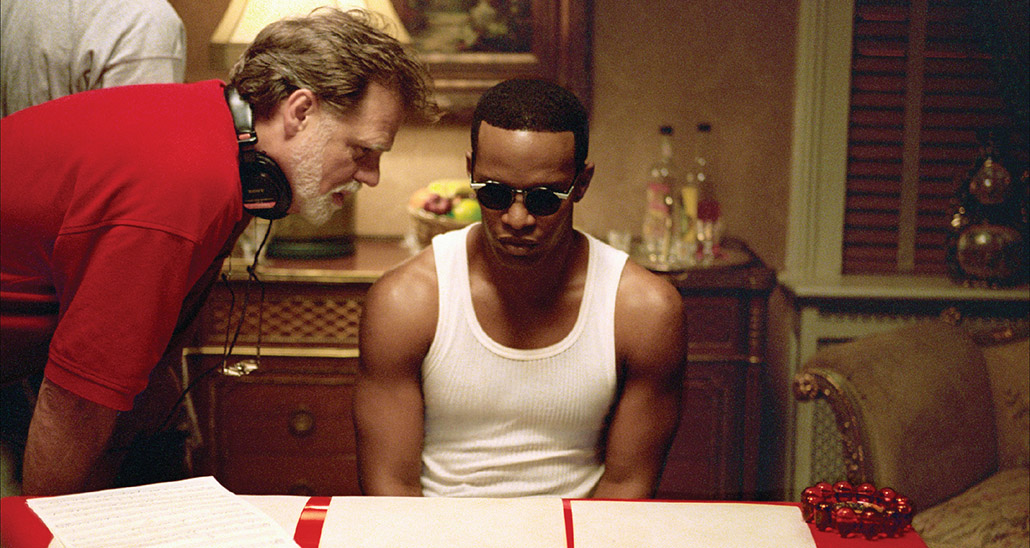

On November 18, Paul and I sat down after a screening of Taylor Hackford’s and Paul’s new film Ray, a biography of the musician/singer Ray Charles. It is a film that effortlessly moves back and forth between Ray’s groundbreaking music career and his early childhood as he developed the blindness that shaped his entire life. We discussed how Paul was able to collaboratively build the style and storytelling of this Oscar contender.

Norman Hollyn: Ray is a huge expanse of a film. How did you get the gig? How long did the film shoot for?

Paul Hirsch: It was originally a 13-week shooting schedule. I came in around week six and went to New Orleans to meet with Taylor. We spent a couple of days together and about four hours together the first day. He was not letting on how he was feeling about me. He said, “You have any questions?” And I said, “Yeah, what do I have to say to get the job?” He said, “Well, we’ll see, we’ll see…”

So the next day we went to the editing room and I came across a strange problem that I also had when I was cutting The Fighting Temptations, which was also a picture shot to playback––actors lip syncing to playback tracks. Nothing was in sync. On The Fighting Temptations, I spent about four or five weeks slipping tracks trying to get them in sync before I discovered that the real problem was the monitor; the new ones apparently have so much processing going on that there is a delay in the image reaching the screen. So I got an old monitor and watched it on that.

NH: We call that “crap inside.”

PH: Yeah, there’s a lot of crap. So Taylor walks me into the cutting room and he says, “Here we have this brand new 50-inch plasma monitor…,” and I said, “It’s very nice except it’s out of sync.” He says, “What?” So I showed him and he said, “Oh my God!” I think that impressed him. So anyway he gave me the job.

I went back to LA and he went off to Thibodeaux, which is this little town Louisiana where they shot all the flashback material. When I started out, they had shot about 700,000 feet of film on the picture. I was so far behind I didn’t have a chance to sit and look at dailies. I would just look at the dailies of the scene I was going to cut that day and then I’d say to Mike [Jackson, Avid assistant], “What do you got have ready for me next?” He was sort of trying to lay track in front of a locomotive.

NH: Do you use a script function in the Avid?

PH: No, it’s the equivalent of that, but it’s just easier to do. I would just cut whatever came up. And I didn’t have the benefit of screening any of the dailies with Taylor. So I called him when I started out and said, “What kind of director are you? Are you somebody who gets it on the first take and then you keep shooting takes trying to match what you did and then eventually sort of give up because you figure you had it on the first take? Or are you working towards something?” He said, “The latter.” And when I looked at the dailies I could see what he was getting at because you could see that on take five, he would introduce a rack focus, or in take nine he would bring the camera up at a certain point. There were ideas that were developing and then he would work to perfect that. So it was clear what his intentions were.

NH: How long was your first cut?

PH: The first cut was three hours and 20 minutes, so and we wound up taking out about 55 minutes. The picture is now about 2:25 plus credits.

NH: One of the things that is fascinating to me is how Ray has a certain structure; it has a style. How did you evolve that style with the integration of flashbacks and the songs?

PH: Well, originally the flashbacks ended in the first three reels. And the drowning scene was so powerful, I said to Taylor, “I really think this scene is so strong that we’re wasting it to use it so early.” And I had this idea that if we held back the drowning scene––and just planted the idea that Ray is haunted by these images of the wash tub and the child’s hand––and moved it to very late in the film, it would create tension throughout the whole picture, so the audience would be wondering, “What the heck is this?”

To his great credit, Taylor said, “Yeah, let’s do it. Let’s go for it.” So we did. And we restructured the picture and it accomplished what I hoped it would. There was this tension through the whole picture, you know, “What is it that’s haunting Ray?” And when you finally got to the drowning scene, it was incredibly powerful. But there was a big problem with this restructuring. Since the rest of the flashbacks were all playing in chronological sequence, taking the drowning scene out sort of confused things. When you got to the funeral, for instance, you didn’t know exactly who she was grieving over. It accomplished what I hoped it would, but the price was confusion, and that was too great a price to pay as far as Taylor was concerned. And frankly I agree with him.

What is great was that he didn’t rag on me about having been wrong; he gave me this freedom to fail. And I think without the freedom to fail, you don’t really have the courage to try anything. But what we learned was that the flashback material, which was very strong, was wasted being used so early in the film. Those scenes were originally written to be in another place, but we ended up proportioning them out through the body of the film, and I think it strengthened the rest of the picture.

NH: On one of the songs, “What Kind of Man Are You?,” you use the framework of the film to almost leap forward in time and to go in and out of time to give background information. The audience isn’t sure exactly where those things occur in time, except that they all revolve around a his personality. Are those things built into the script, or did you develop that? How do you find that style?

PH: Well, there were things that were indicated in the script that would say, “Scene 61, music begins…Scene 62, music continues…Scene 63, music continues…” I realized that there was a plan there, but the trick was how to make it work. “What Kind of Man Are You?” is a very interesting case. I didn’t think about what I was doing at the time, but when I look at it now, I think very interesting because we’re intercutting three minutes with maybe three days. But that’s what the magic of music is like. When the music begins, you’re sort of free to do anything.

NH: Well let’s talk about the music. A lot of the films that you’ve worked on have had music in them in one form or another; The Fighting Temptations, Footloose, Phantom of the Paradise… Do you generally work with temp music as you’re cutting?

PH: Well, I didn’t use to. I used to have this sort of rigorous approach that you should screen the cut without any music. You get the pace of the film right without any music at all, and then you add music and that would be the way to do it. But I found when I did that, there were times when I put in the music and then thought, “Oh my God, it’s playing too fast.” Also, emotional moments in pictures need time; you need some time to feel those moments. And if you go too fast, you don’t get that feeling.

Now, if I know that a scene is eventually going to be scored, I try to find a piece of music that will represent what I think the approach ought to be and then I look at the scene. I don’t cut to that music, but I look at it to get a sense of how long things can play.

“Without the freedom to fail, you don’t really have the courage to try anything.” – Paul Hirsch

NH: You’re using the songs as well as the score and the source music. Were these things written out in the script as to what songs would be where, or did you have a wide canvas on which to play?

PH: No, that was one of the brilliant things about the screenplay; how successfully it used the songs to reflect the subtext of the scenes leading into them.

So that with “Hit the Road Jack,” you understand her anger with him, or with “The Night Time is the Right Time”––they had just been making love in the bathroom and then you get to the studio and she’s singing her heart out to him––you understand how passionate she feels about it. Those were in the screenplay. The interesting thing for me was when a song continued through different scenes as it was playing. I would find little things that would sort of give me a kick, like “I Got a Woman.” There’s a moment where record exec Jerry Wexler is paying off the DJ, slipping some money into his pocket. And I repeated one of the verses so that just at the moment when he slips the money in his pocket, Ray is singing, “She gives me money.” You find those things; those are sort of happy accidents that happen. I’ve always said a good editor is a lucky editor.

NH: So within the confines of the song, you were actually expanding and contracting the music?

PH: Yes. For instance, there were a lot of scenes against one song. They shot in three different clubs––the beginning, the middle and the end of the song. I also had a version of the song without any vocals. So I was able to open up the song, go to a section with just the instrumental and use that as a score underneath the scene. Then, of course, I had to make the scene work within the time I had because songs are very rigorous structures. You can’t take a few frames out…

“Not having a work print, I found, was a real trial.” – Paul Hirsch

NH: Especially in a movie about music.

PH: And especially in blues also; it’s a very strict form. You have limitations, but limitations are great because then you have to figure out how to work around them. I think limitations are a real stimulus to creativity. It’s like with a painting; you have edges to the canvas. If you had no edges, you wouldn’t know where to begin or end.

NH: I really liked how you cut to the music here. One of the temptations is to cut on the beats. You absolutely don’t respect that.

PH: No, I reject that. I like the music to animate the action rather than have the music animate the cuts. You wouldn’t know it to look at me now, but I used to be a pretty good dancer. And anybody who dances knows that if you want your body to be in a particular line on beat “1,” you have to start moving into that position beforehand. It’s sort of like that in editing. When you cut, you interrupt the image.

There’s a phenomenon––the persistence of vision––that enables film to work. Movies are just a series of still images; one after the other. The illusion of movement comes from this persistence of vision. When you cut, it takes two or three frames for your eye to adjust to the new information. I don’t believe in cutting on the “1” beat; you cut just before the “1.” You have to cut early to get the motion. And If the cuts fall in between the beats, it’s the action that leads rather than the cutting itself.

NH: When you approach the editing process on a bio picture or a musical, are you still going for strong character?

PH: Yes, that’s what interests me the most. And I think audiences connect to characters, they connect to story. For a long time there was sort of a prevalent cutting style but now, with the Avid, it’s so easy to change things that people have become more experimental. You’re starting to see cutting styles that you never saw before.

There’s a style I call “cubistic,” which is where you see the same action from different angles over and over again. Like the whole idea of Picasso, where you see both sides of the face at the same time. And then there’s what I call “mannerist” cutting, which is things cut in the style of MTV videos, where the focus is on the editing rather than the content.

“That was one of the brilliant things about the screenplay; how successfully it used the songs to reflect the subtext of the scenes leading into them.” – Paul Hirsch

What I always found so fascinating about movies was that they created the illusion of a place and a time that I really felt I was inhabiting; it was a wonderful way to go to a distant land or to travel back in time or into the future or into a world of fantasy. But the idea was that while you were there in the movie house, you believed the reality of what you were seeing. You accepted the willing suspension of this belief. So, I tend to gravitate to that sort of storytelling, which is to make one believe that it’s a real place in a real time. It’s a real geography. You’re not violating rules of space and time too much.

NH: You said this was the first picture that you’ve worked on without a work print.

PH: Yes. Not having a work print, I found, was a real trial. I never realized how important a tool a work print was. We did Ray as a digital inter-negative, and the engineers who invented this decided for some reason that key numbers didn’t really matter. They don’t scan that part of the frame, they don’t reproduce it. So we get an output to look at, but how do we check sync? It’s like sending the negative off to the negative cutter; how do you know they’ve done it right?

NH: So, how do you know that they’ve done it right?

PH: We screened with a digital projector. It was all stored on a hard drive. The only way to check it is was to put it into the Avid and then eye-match every cut in that reel. So we would do that. We’d find 20 mistakes in the reel! It was out of sync…some places they would drop a frame…there would be a jump in the action… There are two in the film now; we never did manage to fix them. The engineers would say, “Well, that can’t happen.” I said, “Well excuse me, but it did.”

NH: On a more “A personality” note, I know that when I’m cutting there’s usually one or two scenes that are really the ones that refuse to die, the ones you’re cutting until the last minute; and then there a couple that are just absolutely wonderful and you love to keep on going back and working on them. Is there a scene or two in this that you’re particularly proud of or happy with?

PH: I’m proud of the whole film. I think the scenes that I’m most proud of are the ones that I cut and were changed only minimally, rather than the ones that I worked on over and over again.