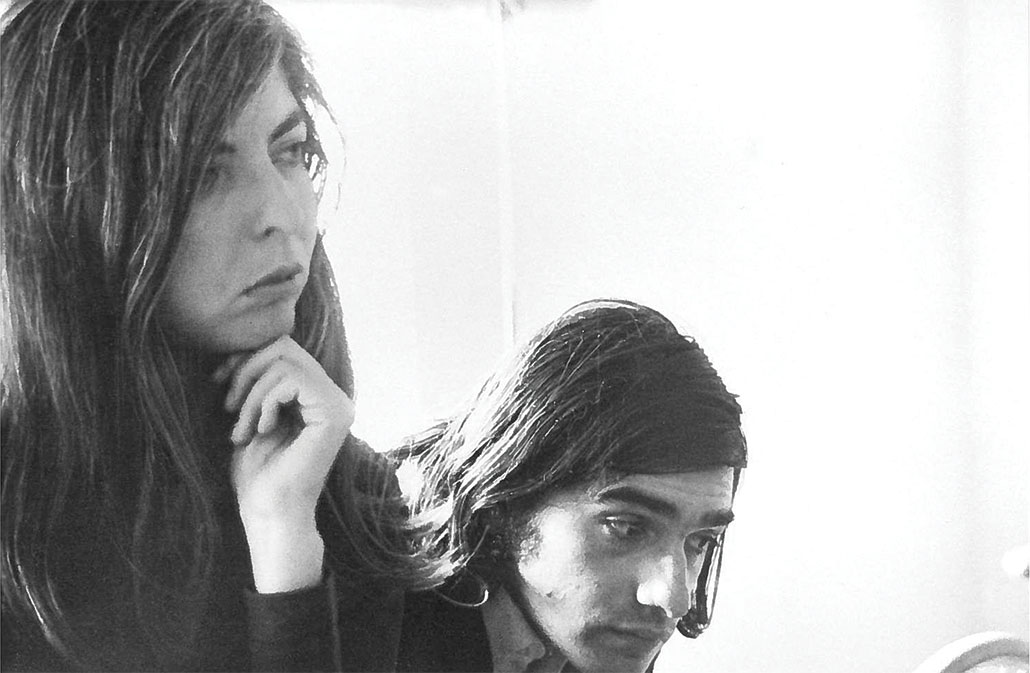

By Norm Hollyn

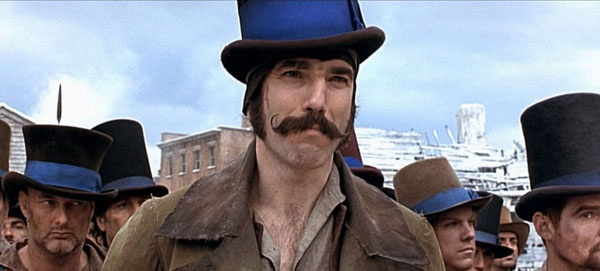

Editor Thelma Schoonmaker and director Martin Scorsese discuss the opening sequence from their new film, Gangs of New York. Set in 1863, in a lawless, poverty stricken area of New York City called Five Points, it is the story of Amsterdam Vallon (Leonardo DiCaprio), who feels he must avenge the slaying of his father, Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson) at the hands of Bill the Butcher (Daniel Day –Lewis). The film also stars Cameron Diaz, Jim Broadbent, John C. Reilly, Henry Thomas and Brendan Gleeson.

Schoonmaker has spent the bulk of her career working with Scorsese – Their first film together was Who’s That Knocking at My Door in 1968. In addition to collaborating on such striking narrative films as Raging Bull, After Hours, GoodFellas, Casino, and Bringing out the Dead, they also have worked together on the documentaries A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies, II Mio Viaggio in Italy and Woodstock, as well as the music video for Michael Jackson’s “Bad.”

The sequence we watched is the prologue, which takes place in 1846. Accompanied by a very young Amsterdam, Priest Vallon leads his gang of poor Irish immigrants through the underground caves in which they live. Once outside, they confront Bill the Butcher and his gang of Anglo-Saxon “Nativists” in a planned gang fight at the snow-covered intersection that is Five Points.

Norm Hollyn: What is absolutely riveting to me is how the sequence sets up both the story and style of the rest of the film.

Thelma Schoonmaker: Marty usually has an editing conception for a film. From the moment he starts dreaming up the shots and writing, he’s always thinking as an editor.

“The cuts were handled so that the camera keeps moving when you dissolve or jump cut.” – Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese: Many of my sequences are storyboarded.

Schoonmaker: I don’t get involved in the storyboarding at all. I usually don’t even look at them while I’m cutting.

Hollyn: How free are you, Thelma, to move away from those storyboards and the script itself in your first cut?

Schoonmaker: On the first cut, I always try and do what’s intended. A director deserves to see what he’s planned. Later, if something would benefit from a change, Marty’s the first person to see that.

Scorsese: Sometimes the original idea may not fit the physical circumstances during shooting, as a lot of it is designed with no actual set or location. Then you have to go back to the original philosophy of the shot and see if it still works.

Hollyn: Do the two of you go through dailies every day?

Schoonmaker: Oh, yes. I take notes like the wind, and Marty is constantly reacting to what he sees and talking to me about how he wants the scene shaped. But in spite of that, he’s never lost the ability to spontaneously feel how an audience will react. This is extremely valuable for a filmmaker. Sometimes he’ll burst out laughing with real enjoyment at something an actor does, and this is very refreshing during dailies.

Scorsese: We talk a lot during dailies about where to cut. And though I try to have a preconceived idea of a camera move or a performance or an edit, sometimes we have to discard it or edit the shot in a different way.

Schoonmaker: I enter these dailies notes onto the card of the selects when I start carving out the footage in Lightworks, and my assistant then prints out those notes onto a log I use during editing, I hardly ever go back to the dailies after that. I just work from the selects.

Hollyn: Thelma, did you do a lot of research into the people and history of the time?

Schoonmaker: I had to learn a lot to direct the group ADR sessions. And in the process of editing the film, I learned from Marty. But I like to come in as somewhat of a blanks slate. Marty prefers that too, because he wants to know if certain things are working. Sometimes there were things that I didn’t understand, and it was important for him to know that, so we could clarify them to the audience. Part of my function is to be a fresh eye.

The scene stars very small and then begins to get more intense. The film begins with a dark screen and a nearly unidentifiable scraping sound, which is revealed in close-ups to be Vallon shaving.

Scorsese: The sound of the razor is originally from Jay Cocks script. That indicated for me how to open the picture. That was designed. So was the part coming up, when we show the caves where these people live- swish pans over to people putting paint on their faces and stuffing their hats for protection from getting hit on the head. But quite honestly, when we looked at rushes, we just talked of a general order in which they should go.

We hear voice over of the older Amsterdam (DiCaprio) describing how he remembers this period of his life.

Hollyn: Is the voice over woven throughout the film?

Schoonmaker: Yes. The trick was to make it poetic and sometimes humorous. We were constantly rewriting it. We did the same on Age of Innocence. This is such a big historical canvas that we had to help the audience along or we would have had to shoot three scenes to explain every little thing.

After Vallon (Neeson) cuts himself shaving, there is a shot of his son Amsterdam. Vallon hands the razor to him and the boy goes to wipe the blood off of it. Vallon stops him, saying, “No, leave the blood on the knife.”

Hollyn: In this scene the camera stays completely on the knife and the boy. Was there any coverage of Vallon that you chose not to use?

Schoonmaker: There was one moment when I thought we should cut to Vallon, but Marty felt strongly that was wrong.

Scorsese: There’s something about how big the razor is in the frame in this shot, how the hand comes in with it. When you track over, when you track over , the boy slides into frame, pure profile. The obvious reference is Spellbound, where Gregory Peck comes down the stairs with a razor and it winds up in a giant close up. The reference is the threat of the razor, not the complexity and the beauty of the Hitchcock shot.

Hollyn: Now you cut from the blackness of the caves to the boy’s hand in his father’s.

Scorcese: There’s this long track out as Vallon and the boy move into the rest of the caves. That ‘s the way we designed it. But Thelma recognized the shots that followed.

Hollyn: You have a little dissolve as you introduce Happy Jack (John C. Reilly) – this is the only one in this whole section. Why not a straight cut?

Schoonmaker: it was more interesting to do the dissolve. Much of the sequence is constantly moving, and you’re discovering things through camera movement. It was very important to keep that idea going.

Scorsese: To keep the camera moving.

Hollyn: Everybody joins together. The scene is really building intensity now.

Schoonmaker: Marty designed a number of swish pans to take us from one shot of people getting ready for battle to others doing the same. However, we sometimes ended up truncating them.

Scorsese: But the cuts were handled so that the camera keeps moving when you dissolve or jump cut.

Schoonmaker: Here’s another one – the swish pan to the man putting on the hat.

Hollyn: Which looked like a jump cut.

Schoonmaker: That’s right. It’s a swish and a jump, because again, we wanted to pick up the pace, so we skip framed and jump cut in the middle of it.

Hollyn: The music propels the tension during this section, too. At what point in your cutting process do you introduce music?

Schoonmaker: Right from the beginning. Marty knew this music, “Shimmy She Wobble”, By Othar Turner and the Rising Star Fife and the Drum Band, was going to bang in as soon as the boy blew out the candle, so we started cutting with it right away. That’s not always the case. Sometimes, he’ll put a piece of music in later. But there are times when he’s actually shot to music on the set. Like “Layla,” in GoodFellas, and here in the caves. In GoodFellas, he designed every shot in the “Layla” sequence to specific bars of the music.

“In the final version, we ended up using the boy mainly as emotional punctuation, not just for his father, but for other characters. That seemed to work better emotionally” – Thelma Schoonmaker

Hollyn: Here’s another abrupt cut as we dolly around the one armed priest.

Schoonmaker: At first we tried a lot of different lengths of dissolves. But then, we decided it would be better to just make a jump cut, because it had more power. And then you see gang members behind the priest, emerging out of the light.

Scorsese: It’s meant to be the creation of a world. I was trying to put as much as possible within the frame. I also wanted to show the varying cultures clashing in New York at the time.

Hollyn: Most of the major characters are now introduced, and we get to this incredible pull-back shot. It’s the culmination of the scenes – the moment when the scene is shot at its widest and most full of life.

Scorsese: That was something designed years ago. I think it was one of the last shots we did.

Monk (Brendan Gleeson) kicks the door, which flies open as the camera dollies though it to reveal an empty, snow swept land scape in the midst of the slum – the Five Points.

Hollyn: From my point of view, this shot is somewhat akin to the bone jump cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey, as we jump from one world to another.

Scorsese: Oh, yeah. But I was more inspired by the door opening in the beginning of Once Upon a Time in the West by Sergio Leone.

Hollyn: Did you do any digital set extensions in the shot?

Schoonmaker: No – It was all a set built for the movie by these incredible Italian artisans at Cinecitta Studios, who are experts at aging things.

Hollyn: We’ve been building up the music, then all of a sudden, we drop to virtual silence.

Schoonmaker: On the kick of the door.

Scorsese: It’s a matter of continuing this sense of not knowing where you are. These are denizens of the underworld, who come out into this foreign space. They’re the dispossessed, and they come up through the ground. The conception of this opening sequence was that with each phase, we show these people gathering, and then you see the environment they’re in. We go further and further, until finally we’re outdoors.

After Vallon’s group assembles, there is a long, slow pan over the Five Corners as the Nativists emerge from a house covered in ice, led by Bill the Butcher (Day-Lewis)

Schoonmaker: I think this is among the most beautiful things Marty’s ever done – the gutsy slowness with which he did it.

Scorsese: Everything was moving along smoothly and flowing quickly prior to this. Now it slows down. The Nativist group slowly emerges, and they position themselves in Paradise Square.

Hollyn: After Bill emerges into the scene you do something interesting – a series of pop-ins into his eye. But to start them, you drop back from the close tilt-up shot to the wide shot, then go in tighter.

Scorsese: Right, My original cuts were wide, tighter and tightest – going straight in. But Thelma felt that it wasn’t effective enough.

Schoonmaker: We could have had Bill come out in a wide shot, so we could begin the pop-ins with the widest image. But we felt that the tighter tilt up to reveal Bill was more emotionally powerful. So in order to get the effect that Marty wanted, we popped back out to the wide, and then I experimented and came up with a rhythm. Our sound editor, Eugene Gearty, gave me these sounds of something like flash bulbs popping to punctuate each cut.

Hollyn: There is a face-off now between the two sides, as the Nativists mass against the Irish.

Schoonmaker: Marty wanted wide shots of these two groups confronting each other like two walls. He wanted the feeling that these were two formidable objects. I had to restrain my desire to cut in to closer shots.

Hollyn: And then you go into these stark, low-angle close shots of individual members of the gangs.

Schoonmaker: Those were originally shot for earlier in the scene. But as I said, Marty didn’t want to use them there. So we decided to do a little montage of them at the end because we loved the faces. It also gave us the opportunity to end with Vallon, as a nice punctuation.

Hollyn: Again, you use sound effects on each cut.

Schoonmaker: We originally had much more dramatic effects but then felt it was better to go with slightly exaggerated sounds of the weapons the Irish gang leaders were holding. As it happened, we had better footage on the Nativist side than on the Irish side. But that was all right with Marty, because he wanted that feeling of the “wall” of people on the Irish side. With the Nativists, we were able to jump cut and repeat actions so that they raised their hatchets twice- a deliberate editing device.

The battle scene that ensues is made up of several elements: Bill is shot primarily in one long tracking shot as he moves though the crowd; Vallon is more or less stationary in the midst of the battle, fending off all comers, and his son has retreated to a mound of snow to watch anxiously. In addition, there are battles involving the other characters we have met in the caves- Hell-cat Maggie (Cara Seymour), Monk and Happy Jack.

Hollyn: The style of the battle scene is very different than a typical action-film fight sequence.

Scorsese: The directions I gave to my second unit director, Vic Armstrong, and to Thelma were to create violence only by implying cause and effect. You never see the connection except through the editing. You never see the actual sword going through a person or a skull being smashed. You suggest it through the intercutting. I gave Thelma further instructions, based on some Russian montages of Eisenstein and Pudovkin from the 1920s.

Schoonmaker: Marty had me look at these sequences, and we ran them several times here in the editing room and discussed them as an influence for the battle scene.

Scorsese: There’s one in Potemkin where one of the sailors is washing a dish. The dish says, “Give us this day our daily bread,” and he smashes the dish, because he has no food. If you look at it closely, it’s about eight or nine cuts, but some of the pieces Eisenstein used were not the actual smashing action. It’s the sailor taking the dish, and you see his arm, his hand. So the pieces of the shots I asked Thelma to take a look at where elements that you would normally discard.

Schoonmaker: Like trims.

Scorsese: I asked Vic to shoot a number of things for me where people were getting hit or pushed or stabbed or fighting, and I gave him directions to move the camera all the time and to vary the speed of the camera within each shot. When Thelma and I looked at the rushes, we chose pieces of those shots we liked – bits and pieces that give the impression of being in the chaos of a battle.

Schoonmaker: The second unit was getting things that you ordinarily would not use but that Marty loved. Little moments of feet in the snow. Of course, the blood splats on the snow are very dramatic. But there were other little things that he encouraged me to keep in the montage. Things that might look like mistakes.

After the two leaders make their challenge speeches, the Nativists cheer and throw their hats in the air as the camera pulls back.

Schoonmaker: We had such a dilemma here. We wanted to let the pullback of the hats thrown into the air continue – let the shot fully play in its great beauty. But when we tried to match the action of the hats flying into the air to the next shot – the boom down as the two gangs collide – we lost the power of the second shot. If we made a perfect match cut, we had to lose too much off the boom down. In fact, we are duplicating the action. They toss their hats here, and then they do it again in the next shot. But we could only overlap the two shots so much before the overlap became obvious. We knew it was much more important to have the boom down, so we sacrificed the end of the first shot.

Hollyn: Now, after all of the slow, static shots, you’re going crazy with the cutting. This is also where the music begins again.

Schoonmaker: It’s a piece by Peter Gabriel called “Signal to Noise.” I would never have thought of it for this area because it’s so slow and sad, but Marty felt that the music showed the futility of the violence. So we cut the battle to that piece. Originally we started it at the very beginning of the battle, but it turned out that it worked much better to have it begin on Bill’s shot. So we had Howard Shore write a short drum piece that we used over the clash of the gangs, and transitioned into the Peter Gabriel piece where we really wanted it to start.

Bill the Butcher starts slicing his way through the crowd, while people fight all around him.

Scorsese: We originally put a shot of the boy watching his father fight as the two gangs collide. That didn’t seem to hold up quite right. I don’t know why. So Thelma finally decided to put this long tracking shot of Bill up there.

Schoonmaker: We made a lot of changes with how the boy was edited into the scene, Marty first thought we would start with shots of the boy watching his father and becoming more and more anxious. But it turned out that intercutting with the boy didn’t work as dramatically as we thought it would. So, we completely revamped the scene and actually lessened the boy.

“You never see the actual sword going through a person or a skull being smashed. You suggest it through the intercutting.” – Martin Scorsese

Hollyn: The boy isn’t actually in the scene very much.

Schoonmaker: At first we concentrated on cutting the battle, and that took a long time. Then we said, “Now we have to put the boy in.” But after we did that, we realized that we were doing it too much. In the final version, we ended up using the boy mainly as emotional punctuation, not just for his father, but for other characters. That seemed to work better emotionally, instead of trying to be so literal with the ending- father, son, father, son. In focusing the scene, we ended up dropping a number of set pieces that were also slowing down the battle. Those are the kinds of thing that you discover when you’re editing.

Hollyn: There must have been an overwhelming amount of footage here. How did you find the pieces you want?

Schoonmaker: It was a matter of feeling our way towards it, with the exception of certain structured shots, like Bill’s. There’s a sequence of some guys jumping through a window and kicking people. And there’s one shot of Brendan Gleeeson trying to find somebody to hit and he yells because he can’t. That was all structured. But the rest of it was really about using whatever worked best dramatically. We kept on trying and trying. We would take a break from cutting the scene and do something else. Two weeks later we would start again and re-cut and re-cut. We finally pared it down to what worked emotionally with the music – rhythmically and visually.

Hollyn: This opening sequence now runs about 12 minutes. How long was it in your first cut?

Schoonmaker: Probably 15. We cut down the caves a bit. But we also took quite a bit out of the battle.

Hollyn: Was there other major restructuring?

Schoonmaker: Mainly how we used Vallon. He is static in the middle of this circular tracking shot, and we found that it worked better to do very quick jump-cutting kinds of things with him. It was important to keep punching him in there, so that the boy is relating to him, and so he has enough weight against Bill, whose shots were more dramatic since he moves around a lot more.

There is a wide shot of the boy stepping out and looking at the fighting.

Schoonmaker: When we began editing this scene, Marty wanted that shot very early on. But we found it was too slow, so we moved it way down. These closer shots of the boy jumping up were actually meant for later on, when the boy sees Bill approaching his father and worries that Bill’s going to kill him. But we found punching him in earlier was more emotional.

Hollyn: Now we see Hell-cat Maggie jumping onto someone and biting his ear off.

Schoomaker: We ended up jump-cutting that section for speed and punctuating it with another hit by Brendan Gleeson. We truncated it a lot to keep the energy going.

Once again, it seems like it’s about maximum impact, energy…

Schoonmaker: … and focus on the characters. When the battle sequence was very long, it had all this great stuff in it, but it needed more dramatic shape. To achieve that, we had to get back to our main characters more.

Hollyn: Now all hell breaks loose, and we’re into a vastly different editing and visual style, How did you decide to make this change?

Schoonmaker: As we began jettisoning stuff, we realized that this little montage of very quick cuts needed to go right before the moment where Bill begins his move towards Vallon. It was just a matter of using any shots that looked strong enough and worked rhythmically, and I did all kinds of variations of it. We actually came upon this montage idea pretty quickly; it was getting the shape of it that took the time.

“[The music is] a piece by Peter Gabriel called ‘Signal to Noise.’ Marty felt that the music showed the futility of the violence. So we cut the battle to that piece.” – Thelma Schoonmaker

Hollyn: There’s nowhere to go after this section except to the kill, because you’ve already pushed the energy up to it’s maximum and most stylized.

Schoonmaker: Exactly. During this sequence, a lot of shots we’re using are, again, like trims. But we loved them. There’s a blurred shot across nothing. There’s a shot, only three frames, of a man with his eye bulging out. No one will ever see those frames when they watch the film on screen – but they’ll feel it. We also have more very tight shots of the boy’s eyes as punctuation.

Hollyn: Now Bill faces off with Vallon, stabs him and watches as he falls back onto the snow. You overlap time here.

Scorsese: That was designed, and I never quite got the overlap right. So we just rippled it up. We had him fall a few times.

Hollyn: It’s interesting to kill off a major star like Liam Neeson in the first ten minutes of the film.

Schoonmaker: The preview audiences were very annoyed with us. They said , “We loved him and you killed him off.” Hopefully you feel the loss throughout the movie, like Amsterdam does.

After Vallon falls, a woman blows a horn, which stops the battle.

Schoonmaker: Marty wanted the sound to be very primitive, Like the wonderful horn in Fellini’s Satyricon. I happened to hear an NPR radio story about lemurs in Madagascar and the female lemur had a very strange call. I suggested to our sound editor that he try it and mix it in with other sounds, which he did.

Hollyn: You also cross the line here, in a very stylized way.

Schoonmaker: First she’s on the right, and then she’s on the left. We were having a little bit of trouble making her horn-blowing look convincing. And we had all kinds of coverage of it. We decided to show her once and then show her completely flipped in another position. It’s not a jump cut, but it should seem deliberately a little odd.

Hollyn: Then Bill leans over Vallon and touches his head tenderly.

Schoonmaker: He says, “It will soon be over, Priest.” He’s just slain this man, yet he’s touching him with such tenderness and compassion that it’s disturbing.

Hollyn: We drop back to the wide, and Bill announces …

Schoonmaker: That it’s over.

Hollyn: Emotionally, we’re done with the battle, Now you direct our emotions to the boy.

Schoonmaker: This has to anchor the whole rest of the film. One of the things Marty wanted to do was show that in the long run, this is a great burden for this boy. He could have had a nice, normal life. But now he has to avenge his father.

Hollyn: The boy grabs the knife and starts to slash away at the Nativists.

Schoonmaker: Yes. So we freeze him. It’s just a moment – five frames actually.

Hollyn: After such a huge, active section, we’re now very personal.

Schoonmaker: You need the quiet moments in order to make more active moments work

A few shots later, after Amsterdan is chased back into the caves and captured, the camera begins pulling back away from the scene of the battle. The camera gets higher and higher, passing through clouds, until it stops high above what we may now recognize as the southern tip of Manhattan. A title card announces “New York City, 1846.”

Hollyn: What feeling did you want the audience to experience here?

Schoonmaker: Sadness, and then the sudden realization that, “My God this is Manhattan.” It should be a very strong reaction. And it always seems to work with audiences.

Hollyn: It‘s quite shocking really.

Schoonmaker: Isn’t it beautiful? It features the five streets coming into the triangle on which so much of the film takes place – Paradise Square. They had the camera on a cable and it had a gyroscope on it to keep it from blowing in the wind. And then, at a certain point, the ILM matte takes over. We let it play as long as we could.

Scorsese: The feeling that I wanted was that no one really should know where they are until the title card pops up at the end of the whole sequence. I didn’t use a main title at the beginning of the film because I didn’t want to give away that it’s New York at the beginning.

Hollyn: This pull back shot is the perfect culmination to the sequence- a combination of old and new in both style and technique.

Schoonmaker: Whenever I talk to students, I say, “Look at old films. It’s all been done before. So learn, look.” I understand that some films students don’t want to do that. But Marty does nothing but look at old films, and he’s taught me so much about the history of film. Those old films are an inspiration. It’s like a painter going to a museum to be inspired. And then from that inspiration, you do your own thing.