by Edward Landler

Since the dawn of our new millennium, about 30 big-budget movies based on the exploits of comic book superheroes have blazed across our screens. Before the end of this July, four more superhero epics hit the theatres. Three of them bring lavishly scaled, debut feature treatments to these defenders of justice: Thor, Captain America and Green Lantern. The fourth is a prequel in the saga of the X-Men. On top of all this, about 20 more comic book superhero films are now in development, prep or production, and planned for release by 2015.

Back in 1932, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster––two teens from Cleveland, Ohio––had no inkling of these future developments when they created the first comic book superhero: Superman. They were just two Jewish kids who consciously borrowed a bit of Christian theology––“He gave His own son to save the world”––to be the thematic underpinning of their idea for a new fictional hero. Launched in a rocket by his father from the dying planet Krypton, the baby Kal-El would survive on Earth with physical powers far beyond those of humans. He would also be instilled with a dedication to the principles of truth, justice and the American way.

This blend of science fiction and morality set in a youth’s understanding of the real world of the 1930s quickly built a following. It spoke to the yearning for personal power and effectiveness that all children have growing up in a world where adults are bigger and seem in control. This hero somehow shared in the elemental role that myth has always played—to impart a faith, a system of values, by which we could follow our dreams and be good—in showing what it means to be grown up in our society.

In 1938, Superman gained national distribution when Detective Comics (DC) bought the rights from Siegel and Shuster. He debuted in Action Comics No. 1. Superman’s popularity led to more costumed superheroes who disguised themselves as ordinary humans when not righting wrongs and saving America––or even Earth––from peril: Batman (1939), Captain Marvel(1940), Green Lantern (1940), Captain America (1941) and Wonder Woman (1941).

Batman and Wonder Woman, both DC characters, joined Superman, Green Lantern and others as partners in special comic editions called the Justice League of America, in which their individual personalities were contrasted. Batman often carped about Superman’s straight-arrow virtues: “What a Boy Scout!”

Inspired by pulp detective fiction, Batman creator Bob Kane gave no super powers to his hero. Except for being the fabulously wealthy Bruce Wayne, Batman was an ordinary human being. He utilized science and technology to hone his skills as a detective, to enhance his mastery of the martial arts, and to intimidate his foes psychologically.

Superheroes got on the big screen for the first time in the 1940s in low-budget serials. In the Batman and Captain America serials, the low budgets were reflected in the production values and the scripts themselves, which seriously deviated from how the heroes were portrayed in the comics. Unlike the comics, these serials underestimated the intelligence of the kids who were their intended audience.

The 1948 Superman serial with Kirk Alyn, though geared toward kids, caught the flavor of the original with a charm that could make an audience look forward to hearing Superman—in the guise of mild-mannered Clark Kent—thinking out loud, “This looks like a job for Superman.” Even the low-budget production values become endearing when Superman turns into a cartoon figure to fly through the air.

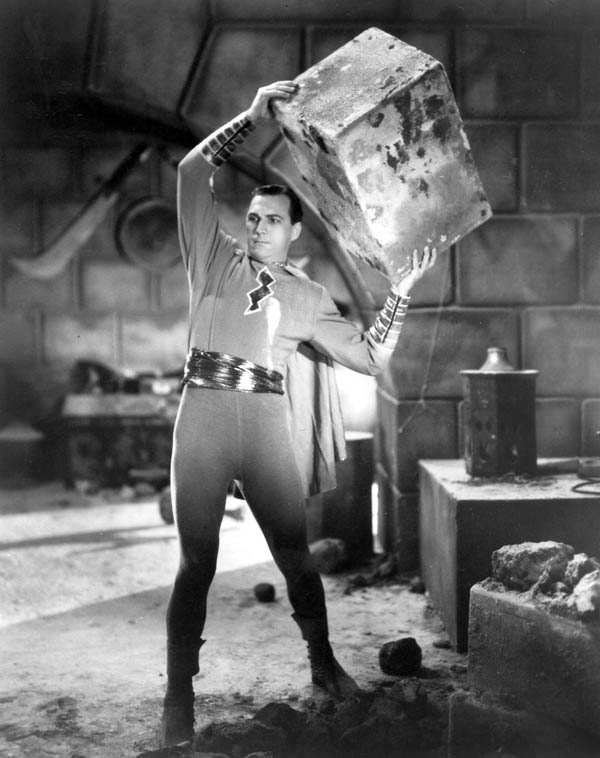

The first superhero serial, Adventures of Captain Marvel in 1941, also retained the essential fun of the comic book with wit and panache. Faithful to the spirit, if not to the letter, the serial happily allows us to suspend disbelief when the ancient mystical sage Shazam transforms teenager Billy Batson—played by Frank Coghlan, Jr.—into the indestructible Captain Marvel—played by Tom Tyler.

Whenever Billy must save the day, he calls out, “Shazam!” and he is given “the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles, and the speed of Mercury”—the initials of the Jewish king and the Graeco-Roman gods and heroes, of course, spelling out “Shazam.” These qualities may appropriately be attributed to all comic book superheroes—at least until more complex psychology and elements of superhero self-doubt took hold with the creative growth of Marvel Comics in the 1960s and the rise of the big-budget superhero features in the 1980s.

But, after the movie serials died out and until the big-budget features came along, superheroes were only seen in the comics and on the TV screen. While the Superman series with George Reeves kept to the straight-arrow simplicity of the comics and the serials, the garish Batman show of the ‘60s replaced the comic Batman’s pulp fiction grittiness with camp artificiality. Though popular enough to have a movie spin-off in 1966, the TV Batman offended the original comic book’s true aficionados with its mocking of the genre.

Meanwhile, a comic revolution was exploding at Marvel Comics with the rise of Stan Lee as editor-in-chief. Concentrating on realistic characterizations and a stricter adherence to the laws of physics than DC Comics, Lee—with his key collaborators Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko—created a pantheon of superheroes riddled with personal issues as they came to grips with the nature of their superpowers. Out of the ‘60s came the Fantastic Four, the Incredible Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Iron Man, the X-Men and Daredevil. In the ‘70s, even more conflicted leading figures emerged—Ghost Rider selling his soul to the devil to save his mentor’s life; the vampire Blade determined to destroy vampires; and the Punisher fighting criminals with criminal methods.

The less graphically violent of the Marvel superheroes joined Superman and Batman as the stars of their own children’s cartoon series, but the Incredible Hulk was the one Marvel character to maintain a long-running TV series. First tested as a TV movie in 1977, The Incredible Hulk series starred Bill Bixby as Dr. David Banner—Bruce Banner in the comics—a scientist who under extreme emotional stress transforms into the giant, green, immensely powerful Hulk—played by Lou Ferrigno—who is unconscious of his normal human identity. Banner’s flight from the military and quest for a remedy for his condition provided a remarkably acceptable ongoing tragic situation for popular family entertainment and, after the series ended, the stars continued in their parts in three more TV movies during the ‘80s.

The popularity of the Hulk’s TV show as a serious and faithful adaptation of the comic book set the stage for the first big-budget, big-screen superhero blockbuster: 1978’s Superman: The Movie, starring Christopher Reeve as the Man of Steel and Marlon Brando as his father, Jor-El, of Krypton. The original comic’s portrayal of Superman as a Christ figure is underscored as the movie Clark Kent travels to the wilderness of the Arctic. There, the crystal sent with him from Krypton transforms into the Fortress of Solitude, in which a hologram of his father instructs him in his powers and responsibilities: “I have sent them you, my only son.” Later in the movie, when Superman is interviewed by a reporter, the reporter tells him, “This is the biggest story since God talked to Moses.”

Through the ‘80s, three more Superman movies with Reeve dominated the superhero genre but their stories veered away from the original’s spirit. The most recent variation, though—Bryan Singer’s Superman Returns in 2006—tellingly begins five years after the events of the Reeve Superman II, with no acknowledgment of the developments in either Superman III or Superman IV. Even more significantly in Superman Returns, Singer works in footage from Superman: The Movie of Brando as Jor-El instructing his son on the essence of his character.

Following the “Superman Decade” of superhero movies, Tim Burton kicked off the “Batman Decade” in 1989. Burton begins his first Batman with the comic book origins of the Caped Crusader—witnessing his parents’ murder, the boy Bruce Wayne grows up to become the emotionally troubled crime fighter played by Michael Keaton. But Burton then drops all fidelity to the comic book’s urban realism in both this movie and Batman Returns in 1992. Instead, he concentrates on action tableaux set within fantastical stage designs of a Gotham City which owe more than a little to Fritz Lang’s 1926 silent film of a futuristic dystopia, Metropolis. Burton’s depictions of the outlandish villains, though more frightening, owe more to the ‘60s TV show than the DC comics.

The last decade of superhero movies—the 2000s—represents a proliferation of comic book characters now brought to the screen in large numbers. The advances in special effects technology and computer graphics, which can lend more realism to the fantastic, certainly contributed to these numbers. But, more importantly, the filmmakers—perhaps childhood fans of the very superheroes they are depicting—have really tried to be more faithful to the human themes underlying the extravagant characters. The best of them re-establish the original idea of the comics as they portray the variations of the human desire to act heroically.

Highlighting themes of human prejudice, the X-Men movies explore the choices of action available to the mutants who are ostracized by human society—peace with humans or mutual destruction. Yet, underlying this conflict is the deeper theme of the growth of trust within Dr. Xavier’s group so that the mutants can combine their super powers for the good of all. What X-Men makes dark and foreboding comes across with a lighter, more humorous touch as the disparate personalities of Mister Fantastic, Invisible Woman (née: Girl), the Human Torch and the Thing settle their differences to save New York City from Doctor Doom in Fantastic Four (2005).

In 2003, Ang Lee directed Hulk, the first transposition of the Incredible Hulk to the big screen, with an imaginative use of split-screen techniques by editor Tim Squyres, A.C.E., to suggest comic book graphics. But Hulk fans rejected his departure from the comic’s anti-militaristic themes to focus on Bruce Banner’s issues with his father to explain his anger and transformations into the Hulk.

Coming closer to the original’s intent, director Louis Leterrier’s The Incredible Hulk with Edward Norton in 2008 focused on the army’s attempt to exploit the science that causes Bruce Banner’s transformations. Tracing Tony Stark’s realization of his industry’s culpability in developing weapons of mass destruction—and updating the action to the wars in the Middle East—Iron Man (2008) also remains faithful to the original comic’s themes.

But the two sets of superhero movies of this decade that do the most to bring their characters into the real world—both physically and morally—are Christopher Nolan’s Batman films and Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man movies.

In Batman Begins (2005) and in The Dark Knight (2008), Nolan makes Gotham City a recognizable place with believable civic corruption and realistic—though stylized—gangsters. Among these gangsters, the more exotic criminals like the Scarecrow and the Joker are not so much cartoonish (as in the Burton films) as they are clearly psychologically disturbed.

Nolan also keeps faith with the original while expanding its themes, especially in Batman Begins. Feeling some responsibility for his parents’ death, Christian Bale’s Bruce Wayne seeks an understanding of his own mission—first by seeking for knowledge and wisdom in the world and later by establishing his relationship to Gotham’s complexly portrayed society. The understanding he seeks is realized in the movie’s key line of dialogue: “It is what I do that defines me.”

Before Spider-Man (2002) turns into a superhero movie, Raimi draws us directly into the New York City of Tobey Maguire’s high school nerd, Peter Parker. His accidental acquisition of super powers only heightens his normal teenage angst about his future and his feelings about the seemingly unattainable girl next door (Kirsten Dunst). Like the Spider-Man comics, the movies bring the issues of dealing with super powers down to the human level.

The resolution of the evil machinations of Willem Dafoe’s Green Goblin in Spider-Man, and Alfred Molina’s Doctor Octopus in Spider-Man 2, is secondary to what Peter learns about himself from them. And what Peter learns is what every superhero––and every ordinary human as well––must learn. “With great power comes great responsibility,” his Uncle Ben (Cliff Robertson) tells him just before he dies—a death that Peter feels he could have prevented.

In Spider-Man 2, Peter is unable to reconcile his super powers with his normal existence, and he renounces his responsibilities as a superhero. But he discovers that the city misses its hero and his Aunt May (Rosemary Harris) tells him, “Lord knows, kids need a hero…courageous, self-sacrificing people setting examples for all of us. I believe there’s a hero in all of us that keeps us honest, that gives us strength, makes us noble and, finally, allows us to live with pride.”

Perhaps the appeal of the superhero movies for adult audiences today is not all that different from what drew kids to the original DC and Marvel comics from the ‘30s on through today. We live in a mass society in which the power of individuals is discounted and threatened by forces seemingly beyond our control. Perhaps some of these tales of superheroes can light a path for us to find the power within ourselves to effect some change and establish our own identities.

Editor’s Note: For more information on Superhero appearances in television and cinema, visit our “Superherology.“