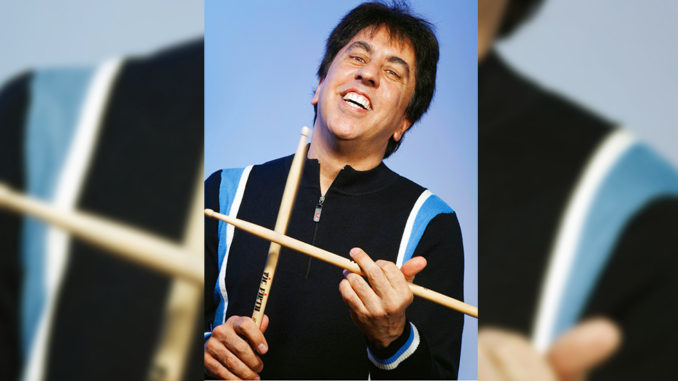

by Rob Feld • portrait by Kfir Ziv

A music editor as well as musician (drummer) who has worked on diverse films big and small, from Martin Scorsese’s The Departed and Gangs of New York to Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and George Hickenlooper’s Factory Girl, Tass (Anastassios) Filipos was recently back with Gondry on Be Kind Rewind. At either end of the filmmaking spectrum, Filipos says his reward has been the work, and tells CineMontage about his experience as a music editor.

CineMontage: Have you found a great difference between working as a music editor on larger or smaller films?

Tass Filipos: Bigger-budget movies can afford to have arrangers and orchestrators and extra help, when on smaller movies you can be asked to work in many related categories beyond just music editing. It didn’t occur so much on Be Kind, but on indie films, I’ve been asked to do everything from orchestrating to playing drums on soundtracks. In that sense, it’s more fun and a little looser. Especially since digital editing machines have come into their own, different rolls are overlapping more. Sound effects overlap with music more. It’s possible to do many more things related to the job, beyond just your “job,” so it’s pretty creative and things can change; unexpected things will arise, and if you know how to do it, they’ll let you.

The other differences are the fact that since the films are low-budget, you frequently make do with what you have, and use your imagination to stretch things to help out the whole production.

CM: How do you choose your projects?

TF: Sometimes I’ll be offered something because they know I’m a musician too, and there’s a lot of on-camera musical performance that needs to be synchronized really tightly. But I’m receptive to working on anything; and by doing that, I’ve gotten calls to do jobs I don’t really know much about at the onset, but that turn out to be wonderful experiences.

“It is frequently the job of the music editor to translate between people.” – Tass Filipos

CM: Michel Gondry’s projects strike me as very musical. He’s a drummer as well.

TF: He started out as a musician and drummer, and made a music video of his band. It got some attention and other name performers started calling him to do their videos. Michel is a really upbeat, positive, energetic kind of guy. The first time I met him on Eternal Sunshine, when we learned that we were drummers, there was an immediate connection. Musicians relate to each other really easily because they speak a common language.

You cut through a lot of the getting to know people when you learn they’re musicians––especially if they play the same instrument, because you probably share similar life experiences: in a practice room for hours, taking lessons, learning how to play with a bass or rhythm section. All the things that go along with your instrument, you know that the other guy did the same thing.

CM: What was Michel like to work with?

TF: Michel was always doing something creative—drawing or using construction paper to make little perspective eye-trick models. He never stops the flow of an idea, even if it’s not related to what he’s doing at the moment. His suite was always filled with music, pads and little models that he was working on. There was kind of a controlled chaos. He must have a master plan in his head, but he’s very open-minded and receptive to the ideas of other people, all the way into the final mix. He’ll ask you to do something that may not make complete sense at the time, but you do it anyway. And after a while, things reveal themselves and unfold into a way of accomplishing something creatively.

CM: Be Kind is clearly made by someone who loves the arts and crafts of making things.

TF: And that’s exactly how Michel is. He likes that kind of unrefined and unpolished thing. Being a musician, a lot of times that aesthetic goes right into my subconscious or emotional response. I’ve been a musician since I was a kid. It almost bypasses my conscious mind, mixes with my own observations of the movie, then comes back out in a way that serves the film. It’s easy for me to work with Michel since I can talk to him in musical terms. You can talk about quarter notes, or a B Flat minor 7 chord, or musical genres. He knows what you’re talking about. Because they’re creative people, all the other people I’ve worked with still get it, but it is frequently the job of the music editor to translate between people.

“Bigger-budget movies can afford to have arrangers and orchestrators and extra help, when on smaller movies you can be asked to work in many related categories beyond just music editing.” – Tass Filipos

CM: What equipment did you work on for Be Kind?

TF: I used my usual ProTools system, but included a couple of software sample plug-ins with which I added orchestral strings and mallet percussion instruments to the film score during the final mix. They were added as an extra layer to the existing tracks.

CM: Was there a particular challenge for you in your work on the film?

TF: In the film, there is a tune called “Fletcher’s Song,” which is used as one of the main themes. It appears as score throughout the film and is also used for the end credits, during which it is played as a vocal song. I received the “Fletcher’s Song” raw tracks from the original recording session, which included only a vocalist and a piano player. My job was to take these vocal/piano song tracks and combine them with a string section track that was originally recorded as a score piece for the film.

The problem was that the vocal/piano track and the string section were not at the same tempo, and some of the underlying harmony was not the same. So I used the Pitch ‘n Time plug-in to line up the tempos, and then used an orchestral sample plug-in to add some string parts to the original string section in order to match the harmony of the vocal/piano track.

CM: Were there any other difficulties?

TF: There were also challenges because I think the picture had evolved quite a bit since Jean Michel Bernard scored it, which is kind of a sign of the times. The way things get done now with computer editing, it’s almost unheard of anymore to wait until the picture is locked before handing it off to the composer. You used to have 12 weeks, which was cut back to nine weeks, which got cut to three. I’ve got such a great respect for the work composers do. They’re asked to tell a story through music and they do it in such a short period of time. God bless all of them.

CM: How was the music done for the so-called sweded movies?

TF: The score was cleverly written to emulate the musical sound and feel of the movie to be sweded. This approach was used in the film as we see Jack Black, Mos Def, and Melonie Diaz in the process of making the sweded movies. But in a couple of places, we used source music, such as the theme from Ghostbusters.