By Kristin Marguerite Doidge

It’s been more than 20 years since picture editor Shelby Siegel, ACE, first became involved in telling the story of Robert Durst and all of its wild – and often tragic – twists and turns. The first order of business back in 2004 was creating a pitch reel for “All Good Things,” which became a 2010 feature film starring Ryan Gosling and Kirsten Dunst, based on the Durst story and for which Siegel served as editor.

“Back then, the filmmakers – Marc Smerling and Andrew Jarecki – mainly made documentaries,” Siegel said. “In order to pitch the fictional film, they went out and interviewed all the real people involved in the Durst story, and so when we put together this pitch reel, it was like a little mini-documentary. But of course, we didn’t have Bob Durst.”

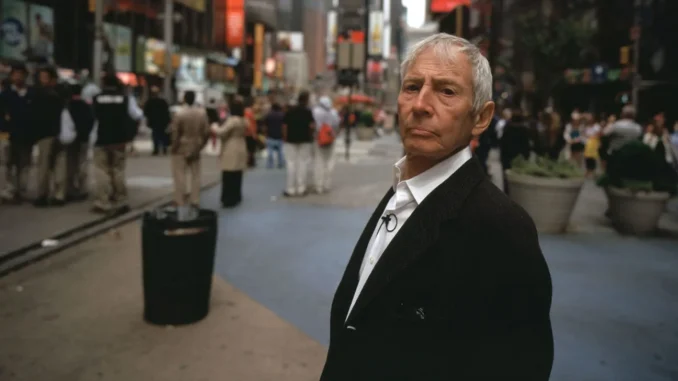

Siegel said all of the interviewees had described the real estate heir from New York – his quirks, mannerisms, and his distinctive gravelly voice – but she and the team never thought he’d consider telling his own story.

But to everyone’s surprise, Durst soon reached out to Jarecki after the film’s release. Durst said he’d been pleased with his portrayal in the film, and the beginnings of what would become the 2015 Emmy Award-winning HBO series, “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst,” were born. The series details three murder cases over four decades that all involve Durst, with new evidence and information being uncovered in real-time. It also features several interviews Jarecki conducted with him in which viewers learn something that would turn out to be key to the story: Durst had an obsession with his own case.

As viewers prepare to dive into “The Jinx: Part Two,” the highly-anticipated sequel to the hit series airing on Max starting Friday, CineMontage caught up with Siegel to hear the improbable and never-before-told story of how she first discovered the now-infamous hot mic audio of Durst’s confession, its impact on both the television series and the real-life case, and the importance of being diligent and open in the editing process.

CineMontage: Tell us about your early days working on “The Jinx.”

Siegel: One of the first things I did when I joined the project in 2014 was watch the first interview with Bob Durst from 2010.

It was fascinating to finally watch this guy who I had only known about through other people’s accounts. I was captivated hearing him tell his story in his own words with all the quirks I had heard so much about – talking to himself out loud during breaks in the interview, and witnessing his ‘tell:’ burping when feeling challenged or nervous.

Andrew [Jarecki, the director] had told me there was a new piece of evidence, but he didn’t tell me what it was, so when I got to the 2012 interview – his second with Durst – I was watching it very much how the audience ended up watching it. I didn’t know what was going to happen. I was on the edge of my seat as much as any audience member would be.

CineMontage: What was the piece of evidence he mentioned?

Siegel: It was a second envelope that had recently been discovered by Susan Berman’s stepson. The handwriting and spelling on the envelope – which had been addressed to Berman on Durst stationery – had an eerie resemblance to the envelope from a previously discovered letter addressed to the Beverly Hills Police Department in 2002 after Berman’s murder. That letter, which later became known as the “cadaver” note, also had Beverly misspelled (‘Beverley’), and Durst had said that the person who wrote that note must have been Berman’s killer in his earlier interview with Andrew. The handwriting on the second envelope was nearly identical.

In the 2012 interview, Andrew is essentially confronting Bob with this new evidence that points to his involvement in the Berman murder – which investigators believe was part of a cover-up of another case – the disappearance of Durst’s first wife, Kathleen Durst, in 1982. And it was in the moments after that confrontation, when the cameras had stopped rolling but Bob’s mic was still attached, that we ended up hearing him talking to himself and making a shocking revelation.

CineMontage: Walk us through what it was like to discover the missing audio from that moment?

Siegel: I am in the edit room watching the footage. I have my headphones on. We were using Final Cut Pro. The sequence had both cameras stacked on top of each other and all the audio on separate tracks.

I see Andrew hand Bob the now-infamous envelope. I see Bob burping and his strange reactions. It’s intense. Then the interview is over, and I hear them looking for Bob’s bag and asking if Bob wants a sandwich. I see Andrew hand him the envelope.

And as I’m watching it, the camera that I’m watching cuts off, but the audio continues. Right at the moment it seemingly cuts off, I hear whispering. And editing 101 is if you hear whispering, you turn up the volume.

Now I am leaning in even further. I’m just listening, and I don’t see anything on the screen. Bob says, ‘where’s the bathroom?’ And then I hear him open the bathroom door, and I hear him say, ‘There it is: you’re caught.’ And I just screamed.

I know what this means. I have known so much about this guy. I’ve spent the last 10 to 15 years thinking about him. I know he has this compulsion to talk out loud and talk to himself. And when he says, ‘There it is,’ I know what the ‘it’ is – if you go back and look at the footage, Andrew shows him the envelope and the cadaver letter, and he asks him, ‘What does this say to you?’ And Bob said, ‘Well, the writing is similar and the spelling is similar [‘Beverl-ey’ instead of Beverly Hills], so I can see the conclusion that the cops could draw.’ And then he burps right away. He’s pretending like this is not new evidence, but this is new. We know from working on the project that Bob knows everything about his case. Andrew has found this letter that clearly shows that [Durst] wrote the cadaver note [which also said ‘Beverl-ey’]. This is what will get him caught. Hence, he’s saying to himself, ‘you’re caught.’

So I scream. And everyone in the room asks, ‘What? What did you hear? Did you find something?’

I assumed this had been heard before, but I took it to Zac Stuart-Pontier, our main editor, to check. He was in his room and he was on the phone, so I’m just pacing like a wild animal outside. I’m just thinking, “Oh my God, I know this is something.” I know it with every fiber of my being. So he finally comes out, and shockingly, he had never heard it. In fact, no one had heard it before.

At that point, the interview was two years old, but if you’re just looking through the footage and you see the camera cut off, you think, “Nothing else here.” I was on cloud nine – I felt like I found the smoking gun – I mean, who doesn’t want to be a detective?

CineMontage: What happened next?

Siegel: I went home that night and I’m thinking about it, and I realize that the audio suddenly stops. The next clip is Durst coming out of the bathroom, so I’m thinking, “Where’s the audio that’s in between?” This doesn’t make sense. There’s something that’s missing.

When I went back the next day, I’m looking through the project, and couldn’t find anything. Then, I hear Zac in the other room saying, “Shelby, have you heard the second part?” Zac, having the same thought as me, went searching and found that missing part, and it turns out it was never loaded into the machine.

The entire staff gathered in the tiny editing room and we’re getting ready to listen to this audio. We’re all holding hands. It was such an intense moment.

We can see it on the timeline. We can see all the waveforms. It’s a very long piece of audio. Bob is going to the bathroom several times, and what’s really happening is he’s arguing with himself because he didn’t tell his lawyer that he was going to do the second interview in 2012, so he is preparing his argument for the lawyer, saying to himself, “Andrew didn’t find anything. It was nothing.” As he’s talking himself through it, we’re watching the waveforms, and then he says the famous line: “What did you do? Kill them all, of course.” We all screamed.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime find that went on to become one of the most talked about moments in television. It’s been cemented into the zeitgeist of popular culture and is still being referenced today. And, it even made it into the criminal case against Durst. A definite highlight of my career.

CineMontage: What other advice do you have for other editors of documentary series after finding such a critical piece of the story?

Siegel: Not every project will have a smoking gun, but you won’t find it if you’re not allowed to look. Nowadays, budgets are slashed and schedules are crunched, so it is hard to be able to really screen everything. But that’s really short-sighted thinking.

What you can learn from watching long, raw interviews with your subject is invaluable and will only pay off in spades going forward, because an editor who is more engaged with the material is going to make a better film, documentary, or TV show. And that is why we do this job. So, I think it’s important that when you can, look at everything and really engage yourself in the material. You never know what you are going to find.

Editor’s note: Robert Durst was convicted of the murder of Susan Berman in 2021 and sentenced to life in prison. He died in 2021 awaiting trial for another murder.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.