by Ray Zone

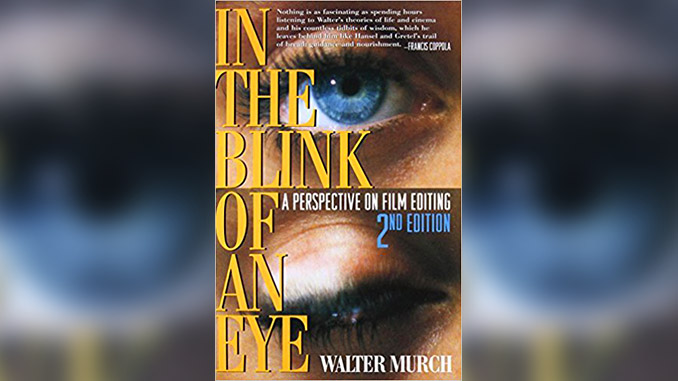

In the Blink of an Eye

A Perspective on Film Editing (2nd Edition)

By Walter Murch

Silman-James Press

148 pps, paperbound, $13.95

ISBN 1-879595-62-2

The second edition of this essential book from Walter Murch, ACE, MPSE, could just as well be called “The Zen of Motion Picture Editing.” Every few years, a motion picture editor should read this book to clear the field of view and refresh the vision about what the craft is all about. For this new edition, Murch has completely rewritten and considerably expanded the digital editing section. In his Preface, the renowned picture and sound editor notes that in 1995, when the first edition of the book came out, “No digitally edited film had yet won an Oscar for best editing” and that since 1996, every winner has been digitally edited with the exception of Saving Private Ryan in 1998.

Throughout this book, Murch poetically makes a variety of comparisons or metaphors for the process of film editing. He characterizes his editing of Apocalypse Now as the “discovery of a path” and for the Colonel Kilgore scenes notes that 220,000 feet of film ended up as 25 minutes of film in the finished product, a ratio of around 100:1. With a movie like this, most of the editor’s time is not spent actually splicing the film, but considering the number of possible pathways that can be taken.

Repeatedly throughout this book, this most philosophical of film editors asks definitively, “Why do cuts work?” He gives a precise definition of the cut as “a total and instantaneous displacement of one field of vision with another; a displacement that sometimes also entails a jump forward or backward in time as well as space.” Murch notes that historically, as soon as it was discovered that cutting “worked,” that the practice of “discontinuity” became “king” in motion picture production. Besides simply rendering discontinuity continuous, he observes that the cut is “in and for itself––by the very force of its paradoxical suddenness––a positive influence on the creation of a film,” and that it would be necessary to cut “even if discontinuity were not of such great practical value.”

In a chapter titled “The Rule of Six,” Murch elucidates the most important values for a good cut. They are, in order of importance: Emotion, Story, Rhythm, Eye-trace, Two-dimensional plane of screen and Three-dimensional space of action. In Murch’s view, Emotion constitutes 51 percent of the value of the cut. It is the thing that should be preserved at all costs––even if it means sacrificing the other values, which are increasingly less important as one descends down the list. Emotion, Story and Rhythm all work together. One should try to have all six values in a cut but emotion should never be sacrificed.

“We entertain an idea, or a linked sequence of ideas… At the instant of the cut, there is a total and instantaneous discontinuity of the field of vision… to separate and punctuate that idea from what follows.” – Walter Murch

Murch uses some interesting techniques to avoid getting caught up in the details of film editing and losing track of the overview. When working with the image of the film in miniature in the editing room, he will cut out paper dolls and place them in front of the screen to maintain a sense of scale similar to that in the motion picture theatre, characterizing the editor as the “ombudsman for the audience.” Despite having the knowledge of how much effort may have gone into a particular shot during production, the editor “should try to see only what’s on the screen, as the audience will.”

Murch also makes a still photo of each scene and arranges them sequentially in the form of a big storyboard. “The most interesting aspect of the photos for me,” writes Murch, is that they provide “the hieroglyphs for a language of emotions.” This isn’t Murch’s only reference to hieroglyphs. In a footnote, he observes that visual discontinuity “is the most striking feature of ancient Egyptian painting” and that each part of the human body is represented in this venerable language “by its most characteristic and revealing angle.”

Similarly, when Murch assembles his storyboard by choosing representative film frames, he is looking for “an image that distills the essence of the thousands of frames that make up the shot in question––what Cartier-Bresson called the ‘decisive moment.’”

Murch also stands up while editing, whether he is working at a Moviola, a KEM Universal or an Avid. He characterizes editing as “a kind of dance” and the finished film as a “crystallized dance.” By standing during the editing process, he is able to physically get in touch with that visual dance that takes place in the film, with its own temporal rhythm and movement.

The editor refers to test screenings of rough cuts as an examination of “referred pain.” An audience at an exit poll might identify an individual scene as a problem, but Murch notes that the “pain” of that scene may be a result of the fact that “the audience simply didn’t understand something that they needed to know for the scene to work.” Some exposition that took place before the scene itself might require clarification. That’s an example of a localized “pain” that is generated elsewhere in the “body” of the individual artwork.

In Murch’s view, Emotion constitutes 51 percent of the value of the cut. It is the thing that should be preserved at all costs––even if it means sacrificing the other values.

Murch also examines the violence of the cut. “At the instant of the cut, there is a total and instantaneous discontinuity of the field of vision,” he says. When editing The Conversation in 1974, he began to understand the importance of the human blink to the filmic cut. We blink, not just to moisten the aqueous orb of the eye, but psychologically because “we entertain an idea, or a linked sequence of ideas” and need “to separate and punctuate that idea from what follows.” The motion picture cut, therefore, extends this visual and psychological need into the medium itself.

Murch’s book should remain in print for a long time to come. It is a foundational work from one of the most erudite thinkers––and practitioners––in the motion picture field.