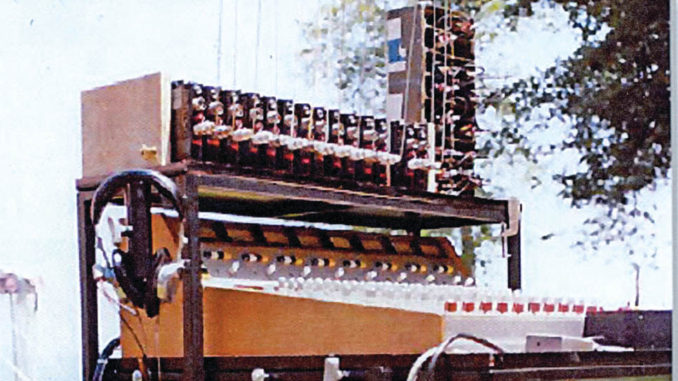

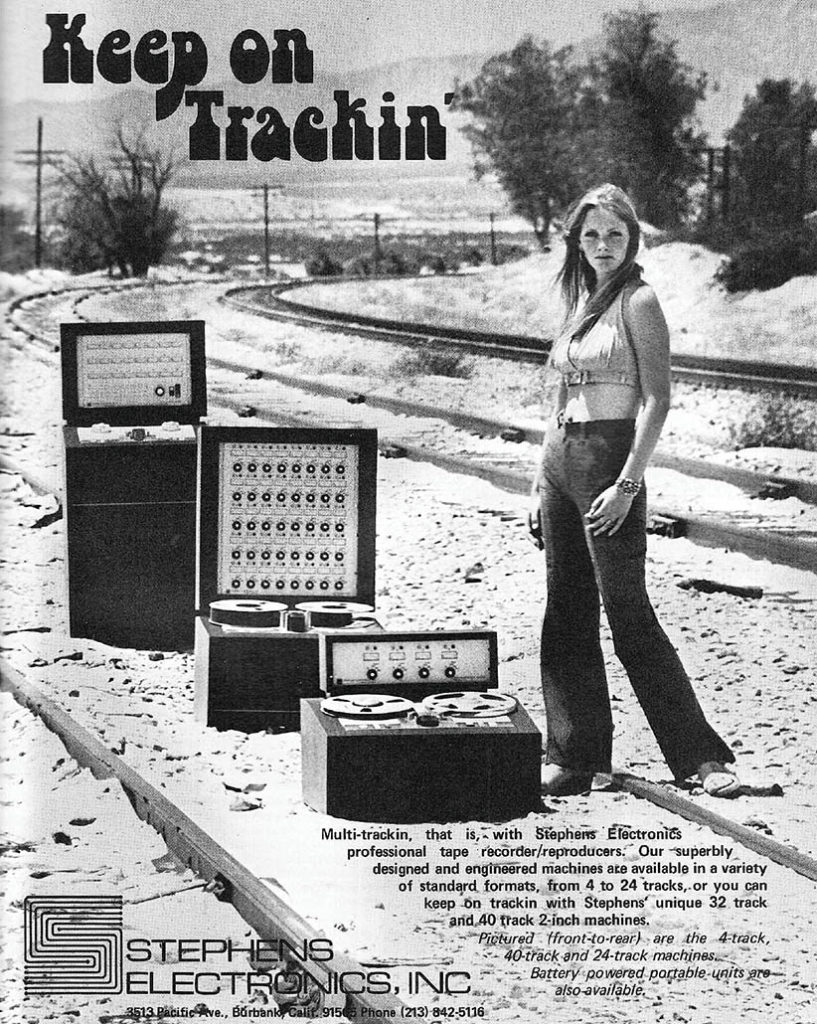

I would like to add an additional facet to the This Quarter in Film History article, “Altman’s Grand Ole Soap Opry”. In the past, most articles that have dealt with Robert Altman’s use of 8-track machines to record simultaneous actors’ dialogue fail to mention one thing: John Stephens (my brother) made it all possible, many years prior to the use by Altman and his sound crews on films such as Nashville, through the development of a portable, 59-pound, battery-operated 8-track machine (see accompanying photos).

John’s path to the creation of the 8-track decks used by Altman and production mixer Jim Webb began when he developed his own unique plug-in, solid-state audio amplifiers and record circuits (Op Amps), and accompanying record/playback headstacks starting in 1965. At that time, he converted a series of early commercial Telefunken and Ampex transports from half-inch 4-track to one- inch 8-track capability for customers who also wanted his improved wide range audio replacing the dated tube electronics. Then, in 1968, he started to manufacture his own 8- and 16-track machines using the transport only of the newly marketed 3M 8-track M79 recorder. He retained just the basic top plate and gutted the deck, installing new, beefier motors, plus his electronics.

John actually sold four of his 8-track machines to Altman’s post-production company, Lion’s Gate Films, in 1973, 1974, 1977 and 1979. Those were the decks that Webb knew about and had recommended, since he had used them to record on-location rock concerts and studio sessions for artists such as the Grateful Dead, Ike and Tina Turner, Leon Russell, Pink Floyd, the Cars and John Farrar, to mention a few.

Later, when 3M started seeing him as a competitor, they would no longer sell him the deck by itself. As a result, John created the first capstan-less, reel-to-reel transport that was completely servo-controlled by the feed and take-up reels without any mechanical brakes or other linkage. When people looked at the underside of the transport, they would often ask, “Where’s the rest of it?” John’s motto was “Keep it simple” and then, “Let’s simplify it even more.” He was always modifying and improving each machine that came off the assembly line, and much of his return business was in updating his customers’ older models. He went on to create 16-, 24- and 40-track machines (the latter one of a kind) as customers began to ask for even more tracks on which to record. Even today, there are some remaining studios that still master on Stephens analog machines for their unique, wide-range sound and legendary low-frequency response.

I appreciate the opportunity that our own publication, CineMontage, has offered to give credit to John (we in the motion picture business know how important credits are!) when so few people and magazines have failed to do so. Even though he has passed on, I know it will give John a smile. And I’m sure many of the recordists and audio engineers who have used his decks would also applaud a posthumous recognition of John Stephens.

Roderic G. Stephens,

ACE Picture Editor (Retired)

Redding, CA