by Kevin Lewis

It is highly unlikely that the recent golden anniversary restoration of The Girl Can’t Help It, directed by Frank Tashlin and released by 20th Century Fox on December 1, 1956, will be re-examined by highbrow critics at art-house venues, but the movie’s CinemaScope cinematography and Mamie Eisenhower pink-and-cobalt-blue color scheme underscore what was then a still-raw, primitive American pop culture. Yet, that film represents Hollywood’s first serious crush in its 50-year love affair with rock ‘n’ roll. The love for rock ‘n’ roll has certainly not diminished over time and it has even grown as new lovers have found a home in that genre. This is why throwback concerts are still put on to this day through resources such as bargainseatsonline.com, as well as similar other services, so that people can relive the atmosphere of that time or get an experience of what it could have been like.

But the initial rock ‘n’ roll films produced in the mid-1950s, and the American Bandstand television broadcasts, which actually began in 1952, are more interesting today as artifacts than as art. These sanitized versions of a raw and erotic music form expose a society uncomfortable with sexual urges and connotations. The films were editorially crude, and suffered from poor sound reproduction. Even so, teens, galvanized by the new sound, wanted to see their favorite performers and even held American Bandstand dance parties in their homes after school.

By the 1960s, picture and sound editors and re-recording mixers were inspired to experiment with montage and audio to create a new film language using rock ‘n’ roll music and how it was presented. That language helped to enable a closer relationship between film and sound editing, and rock ‘n’ roll music can now be used as a component in film narrative, as a comment on the plot or as a counterpoint to the action.

Exploiting the Devil’s Music

Because rock ‘n’ roll in the 1950s was associated with everything that was threatening to phobia-ridden, youth-fearing America, it provided fertile ground for such exploitation producers as Sam Katzman, Roger Corman, Samuel Arkoff and Albert Zugsmith to create a slew of salacious drive-in movies. Even such experimental filmmakers as Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol used the rebellious music to give meaning to the social outsiders in their films.

The groundwork for the early rock ‘n’ roll musicals was actually laid in the 1940s and early 1950s with a series of musical shorts, second features and films made largely for minority audiences. Such rock ‘n’ roll forerunners as Cab Calloway, Louis Jordan and Nat “King” Cole appeared in “soundies” and Snader Transcriptions films, specifically produced for such non-theatrical venues as coin-operated loop motion projectors in train stations, bus depots and small nightclubs.

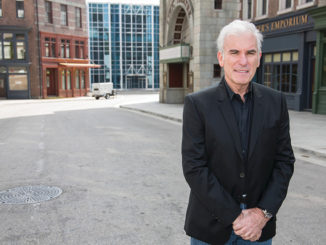

Courtesy of Charles Connor Archives Copyright Columbia Pictures

These musical shorts created an audience for rhythm and blues music after World War II and paved the way for acceptance of this sound in both white and black America. Jordan even made feature-length films for poverty row studios, with such catchy titles as Reet, Petite and Gone (1947), and made cameo appearances in major studio releases like Follow the Boys (1944).

Though the first appearance of rock ‘n’ roll in movies is traditionally dated to the playing of Bill Haley and the Comets’ hit single “Rock Around the Clock” over the opening credits of The Blackboard Jungle (1955)––a film which linked youth gangs in high schools to the corrupting power of the new music––this was not the film debut of early rocker Haley and his band. The group had made a three-song concert short (a precursor of music videos) called Round Up of Rhythm in 1954 for Universal Pictures. Ironically, the two mainstream studio movies associated with juvenile delinquency, The Wild One (1953) and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), used no rock ‘n’ roll music at all.

Rock Knocks, Hollywood Answers

It wasn’t until 1956 that Hollywood discovered rock ‘n’ roll. That year, Columbia Pictures released Don’t Knock the Rock and Rock Around the Clock, both produced by Katzman and featuring legendary Cleveland disc jockey, rock ‘n’ roll advocate and concert host Alan Freed. A small company called Vanguard also produced Rock, Rock, Rock that year, and Jamboree the next. The value of these films today is the visual record they provide of such seminal performers as Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, LaVern Baker and The Platters, among others. The tame performances, however, did not convey any of the tension and audience frenzy that was part and parcel of a rock ‘n’ roll show.

As was usual in the Hollywood studios, the musical numbers were recorded first and then the performers mimed playing their instruments, and the singers lip-synched to playback. As Charles Connor, Little Richard’s original drummer, who appeared in The Girl Can’t Help It, Don’t Knock the Rock and Mister Rock ‘n’ Roll (1957), recalled, “The music wasn’t recorded from the band’s own playback, but from recordings originally produced months before.” Connor also estimates that the groups were on the sound stage for less than two hours miming their songs as their scenes were filmed.

The Girl Can’t Help It was the first “A” picture to recognize rock ‘n’ roll as a cultural force. Though it featured a spectrum of acts that ranged from African-American rhythm and blues ensembles such as Little Richard and his band, the Treniers and the Platters to white proto-rock guitar gods like Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent to doo-wop groups like the Chuckles, the film’s schizoid structure reflects the indecision and uncertainty that the Hollywood studio system had about this nascent sound. Its plot was no different than a 1940s Betty Grable musical––a fact underscored by the use of a Grable film clip watched by the jukebox gangster protecting the Jayne Mansfield character in the film.

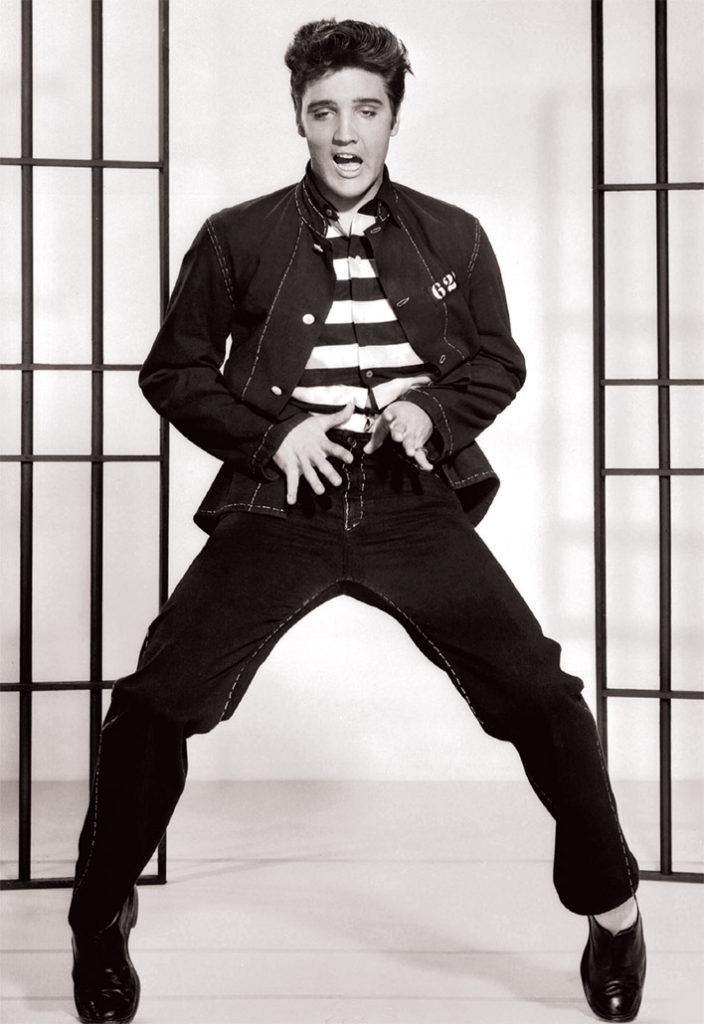

The Girl Can’t Help It was also the last major rock ‘n’ roll movie until the 1960s to feature African-American performers. Things were beginning to change; rock on film was becoming white bread and safe. By 1957, Fox was concentrating on films starring Pat Boone, and Hal Wallis was producing the films of rock ‘n’ roll’s first superstar, Elvis Presley. Other than Elvis, rock ‘n’ roll on screen was reduced mostly to Connie Francis movies at MGM and Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello beach party movies at American-International Pictures.

Capturing Rock’s Sound for Film

When the studios did not use records for playback, the songs were re-recorded in sound studios like the Gold Star Studio in Los Angeles, according to music historian Robert Leslie Dean. Ted Whitfield, a sound editor for the television series The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet in 1957, recalls that series star Ozzie Nelson took his 16-year-old son, musician Ricky Nelson, around town to sound studios to record his songs for the show, because the Hollywood studio recording rooms did not have the technology necessary to record rock ‘n’ roll.

Re-recording mixer Richard Portman, whose father Clem Portman was a sound recording pioneer, says that picture editors took their rock ‘n’ roll tracks to his father’s studio at Goldwyn in the 1960s for pre-dubbing and equalization before the final mix. Because rock ‘n’ roll was considered more ephemeral than Hollywood musicals, production dollars went elsewhere. Besides, the symphonic-oriented Hollywood studio musicians, like many others in the industry, didn’t take rock ‘n’ roll seriously. According to BMI archivist/historian David Sanjek, performing rights organization ASCAP didn’t even seek out rock ‘n’ roll composers for inclusion among its members because it had so little regard for the genre.

Editor Lisa Day, re-recording mixer Steve Maslow and sound editor George Watters II, MPSE, re-created the look and feel of the Alan Freed concerts in two latter-day movies, American Hot Wax (1978) and Great Balls of Fire (1989). They concur that the content was more tame and restrained in the 1950s and early 1960s concerts, and that’s what they strived to duplicate. Day recalls, “The style of our films was the sanitized 1950s-60s, but the content was more in today’s style, meaning [more revealing biographical content].”

When Maslow, who grew up in Los Angeles in the 1950s listening to the early rock ‘n’ roll, was preparing his Freed concert sequences for Great Balls of Fire, the biopic on Jerry Lee Lewis, he had Lewis record all new versions of his songs. Maslow “tried to capture the essence of the vibe,” but did not attempt an exact reproduction of the way the music sounded 30 years earlier. “The original recordings were monaural, but we had stereo capability––and we certainly used all the speakers to fill the room with music,” he says. Maslow claims that Lewis was “a lot wilder in Great Balls of Fire“––both in Dennis Quaid’s on-screen portrayal of him and in the recordings the music legend made for the movie––than the way he presented himself in those original films. “Actually, I remember seeing Jerry Lee in the Columbia and Fox movies when I was a teenager,” he adds. “I became somewhat interested in the music after seeing those shows––but I never used them as a reference point for my show. That was never a consideration.”

Watters, who grew up in Southern California in the 1950s and early 1960s, remembers the many local and national television shows which showcased rock ‘n’ roll. He emphasizes that the adoring shrieks of the audience were sometimes missing from films like American Hot Wax. So he worked on creating crowd noises, which at times competed with the music or even overpowered it. Re-creating that sound was in itself a daunting task because of the limits of 1978 sound technology.

Watters also created the street sounds in American Hot Wax, especially for the doo-wop groups who sang on street corners outside the Brooklyn Paramount Theatre with high hopes of being discovered and invited inside. “American Hot Wax was meant to be a raw and realistic interpretation of the unsophisticated sound of that era, with its small amplifiers, tinny PA systems and screaming teens drowning out the music,” Watters explains.

Sound editor Bert Lovitt was the post-production supervisor on Let the Good Times Roll (1973). On that film, he insists that there was no initial plan to use archival rock footage, but that changed when the researchers unearthed not only the Katzman films at Columbia but also The Girl Can’t Help It and 1950s high school educational films from the Sherman Grinberg Film Library. That additional material was intercut with the concert footage, or used in split-screen fashion, with 1972 performances by Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Bill Haley.

“We were not allowed to use the old soundtracks from The Girl Can’t Help It,” Lovitt says. “But we had the right to re-perform them, so we used fresh tracks for the footage.” The footage of Little Richard from 1956, stripped of its soundtrack, was synched to the 1972 concert soundtrack. Because it was a live concert, the new tracks include the audience’s reactions, which had a dynamic quality absent from the original movies.

“In retrospect, the earlier films have power, but they were not taken seriously by those in the Hollywood establishment of the time––who were really blind to the youth culture that was sneaking up on them,” Lovitt explains. “They did not pay any attention until Easy Rider [1969] and Woodstock [1970] really shook the tree.”

A Compromised Time Capsule

The films and television shows of the 1950s did not provide an accurate portrayal of how the music was affecting and changing a young generation, and how the establishment resented and resisted it. But they are all we have as a time capsule of that era in movie history when rock ‘n’ roll reared its rebellious head. Ultimately, the greater value of these films is in their cannibalized form as part of documentaries. In that context, with analytical narration and creative editing, we can re-examine that period in a far more realistic way.

And fans of both popular music and cinema can thank their lucky stars that rock ‘n’ roll and Hollywood have gotten along better as they––and their relationship––matured.